School of Meanies (5 page)

The Still-Alive Headmaster

“I’m glad we decided to be friends,” Amelia said that afternoon. “School recess can be fun now.”

We sat together on a bench at the edge of the playground. Well, Amelia sat, and I floated.

“I can eat my ordinary chips,” Amelia said as she crunched, “and you can eat your ghost chips, and—”

“But, Amelia, you’re crying.”

“School is horrid,” Amelia said, and she blew her nose on her left braid.

“It needn’t be, now that we’re friends.”

Amelia shook her head. “There will always be bullying in this world, Humphrey, no matter who you’re friends with.”

“Bump them, like how I taught you.”

“There are some bullies who just can’t be bumped.”

“I’m not afraid of any bully,” I said, and I munched another creepy chip.

Amelia frowned, then looked at me and said, “You’d be afraid of this bully.”

“Why? Who is he?”

“The headmaster.”

I laughed, spilling chips down my blazer. “I bumped the Ghost Headmaster at Ghost School. No one bullies Humphrey Bump.”

“Didn’t you get into trouble?”

“He’d already expelled me,” I explained. “That’s why I’m here, at Still-Alive School.”

“Humphrey, I can’t get expelled. I’m top of the class in science. I plan to go to college.”

“Then you’d better stay out of his way,” I said, opening another bag of chips.

“I can’t,” Amelia said, and she began to cry again. “I have to see the headmaster today after school.”

“But why?”

Amelia sniffed into her chip bag, and said, “For bumping bullies.”

At last bell, I floated in through the window of the Still-Alive Headmaster’s office and wisped behind the potted plant.

As I peered out between the dusty green leaves, I heard a faint phantom blub.

“Wither,” I whispered, “is that you?”

“I’m hiding in the hem of the curtain,” Wither blubbed. “I wisped in, and now I can’t wisp out.”

“What do you mean, you can’t wisp out?”

“The Still-Alive Headmaster is mean,” Wither blubbed.

“You don’t get to be a headmaster without being mean, Wither.”

“This headmaster is so mean he makes other headmasters seem hardly mean at all.”

“But, Wither, why did you float into the Still-Alive Headmaster’s office in the first place?”

“I wanted to see how mean he was,” Wither said, and he blubbed.

The office door opened, and a girl walked in. “Humphrey,” Wither sniffed, “that girl looks familiar.”

“She’s my still-alive friend, Amelia,” I whispered. “Amelia has been sent to the headmaster for bumping bullies into the hedge.”

“That’s triple mean,” Wither blubbed. “The bullies were mean to Amelia, then Amelia was

mean to the bullies, and now the Still-Alive Headmaster—”

“Keep quiet,” I whispered. “I want to hear what he says.”

From my hiding place behind the leaves of the potted plant, I could just make out the Still-Alive Headmaster sitting at his desk, and Amelia nervously biting her fingernails.

“Well?” the Still-Alive Headmaster yelled. “What do you have to say for yourself, child?”

“I’m sorry, sir,” Amelia said. “Um, it won’t happen again, and—”

“Not good enough, child!” the headmaster yelled, his face the color of a beet.

Amelia backed away as the Still-Alive Headmaster stood from his chair and leaned toward her across the desk, jabbing the air with a spiny finger.

“Lines!” the Still-Alive Headmaster yelled. “Ten thousand, in your neatest handwriting.

Fifty hours litter duty. And two hours of detention each day for a month.”

“Oh, the meanness!” Wither blubbed, and he wisped up from the hem of the curtain and floated out through the office window.

For a moment the Still-Alive Headmaster looked almost afraid. “What in heaven’s name was that?”

“A friend of a friend,” Amelia said, and she walked out of the Headmaster’s office with a smile.

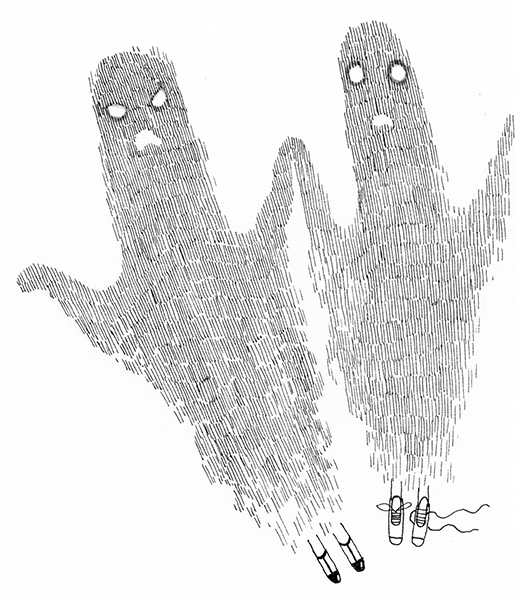

Who’s Afraid of Humphrey Bump?

“Haven’t you noticed,” Amelia whispered on Wednesday afternoon, “how unhappy everyone is?”

“I’m sure they’d rather be out riding their bicycles in the sun,” I said, peering out from Amelia’s satchel. “Anything other than opening their math books.”

“That’s not what I meant.” Amelia sat at her desk and lowered the satchel to the floor. “School days are supposed to be the best days of your life. Ever since this new headmaster arrived last semester, I’ve not seen one cheerful face.”

I broke a chunk from a ghostly chocolate bar and popped it into my mouth.

“And look at how tired everyone is, Humphrey.”

I peered out of the satchel and glanced around the classroom. Two of the boys had their heads in their arms. One girl was snoring loudly. “They stayed up late watching cartoons, I guess.”

“Cartoons? Humphrey, after a day of lessons, followed by five hours of homework, I doubt they can keep their eyes open.”

“Five hours of homework?”

“Headmaster’s rules,” Amelia whispered. The room fell silent as the Still-Alive Headmaster

strode in on his long, mean legs. He glanced around the classroom, and then pointed at a boy in the front row. “You, child, where is the teacher?”

“You—you fired her, sir,” the boy stammered.

“Raise your hand when you speak, child,” the headmaster yelled, and the boy raised his hand. “You’re expelled. Gather your pencils, child, and get out.”

“You can’t expel a boy for forgetting to raise his hand,” I whispered.

“We’re lucky he’s in a good mood,” Amelia whispered back, “or he’d have expelled the entire class.”

“He can’t do that!”

“It’s happened before, Humphrey. I told you the headmaster was a bully.”

“Well, it’s got to stop,” I said.

“Humphrey,” Amelia gasped, “what are you going to do?”

“You’ve heard of things that go bump in the night? Well, I’m going to go bump in the daytime, right here in this math classroom.”

“You’ll get yourself into trouble.”

I loosened my school tie. “What can he do, expel me?”

“Just be careful, Humphrey.”

“He’s the one who should be careful,” I said, and I wisped out from Amelia’s satchel. The still-alive children screamed and ran out of the classroom, and the Still-Alive Headmaster backed into the corner. I took a deep breath and gave the Still-Alive Headmaster the bumpiest bump I’d ever bumped.

“Ghostly child,” the headmaster said, straightening his hairpiece, “surely you can bump me better than that?”

“What do you mean?”

“Must try harder,” the Still-Alive Headmaster said, and he walked out of the classroom.

“But that was my best-ever bump,” I said, tugging a jam doughnut from my blazer pocket. I’d intended to bump him again, but somehow I’d lost heart.

“Perhaps you don’t need to bump him,” Amelia said from the doorway. “You’re a ghost, Humphrey. Most people find ghosts terrifying.”

“I’d forgotten about that,” I said, and I wisped down the corridor, wriggling my transparent bits and making a mean face.

The Still-Alive Headmaster just stood there shaking his head—pitifully,

I think.

“I’m a ghost,” I said. “Aren’t you afraid?”

“Not in the least,” the Still-Alive Headmaster said, and he walked away.

Humphrey’s Speech

Thursday morning, as I floated across the field to Still-Alive School, I bumped into Wither.

“I thought you’d stopped all that bumping nonsense,” Wither said.

“Sorry.”

I told Wither about what had happened with the Still-Alive Headmaster in the math classroom.

“Some still-alives are afraid of ghosties,” I said, “but not this still-alive. I wriggled my transparent bits and he didn’t bat an eyelid.”

Wither rubbed his chin. “And you bumped him, you say?”

“Left, right, and center,” I said, picking an apple from a nearby apple tree.

“He must be afraid of something. Every still-alive is afraid of something.”

“Well,” I said, “he did look afraid when you wisped out from his curtains. Only for a moment, and then he sort of pulled himself together.”

“Hmm,” Wither said. “It seems to me that this mean-spirited still-alive is indeed afraid of ghosties, but only a bit.”

“What are you getting at?” I said, crunching the rosy apple.

“It’s like this. Let’s say I’ve just penned a quite-good poem. If I wish to lift the poem to greatness, I simply write a further two hundred verses.”

“But that makes the poem worse,” I said.

“Your poetry is drivel. The less of it there is, the better.”

Wither didn’t seem to hear. I think he was lost in a poetic reverie or something.

I tossed the half-eaten apple into a hedge. “Wither, I know you’re trying to help—”

“Allow me to finish,” Wither said. “If this headmaster is afraid of one ghosty a bit, he will be afraid of a lot of ghosties a lot.”

I thought about this for a moment, then said, “That actually makes sense.”

“Let’s see.” Wither held up his knitting-needle fingers and began to count. “There’s myself, you, and I—that’s three. And the three girl ghosties makes six. And then there’s Charlie.

And Humphrey—that’s you—which makes eight—”

“Shh,” I said. “Listen.”

Wither cupped his ear with his hand. “But, Humphrey, you’re not saying anything.”

“Not to me. To, um, everything else.” We listened.

Wither said, “I can’t hear anything. Well, only the ghost children at Ghost School across the field there, but—”

“Wait here,” I said, and I flitted across the field and over the high gray wall and into the Ghost School playground.

After a quick float around, I spotted Samuel Spook floating by the bike shed.

We used to be good friends, but when I wafted across the playground toward him he turned up his nose.

“Samuel,” I said, “I need your help. There’s this headmaster at Still-Alive School, and—”

“I can’t hear you,” Samuel said, and he poked his fingers into his ears.

“But, Samuel, we’re friends.”

“After you bumped me into the sausage trolley in the cafeteria?”

“I’d forgotten about that.”

“Fight your own battles,” Samuel said, and he floated off.

Just as I felt ready to give up and wisp back to Wither, I spotted the terrifying twins, Phil and Fay Phantom.

When I floated over, Fay folded her arms, and Phil looked through his shoes.

“I need your help,” I said. “There’s this headmaster—”

“You’ve got nerve,” Phil said.

“You bumped me into the swimming pool,” Fay said and tossed her hair.

“Only in fun, Fay.”

“And you bumped me down the stairs,” Phil said. “If I wasn’t dead, I might’ve been hurt.”

“I can explain.”

“Don’t bother,” the twins said together, and off they wisped.

I floated, slowly, back over the high gray wall and across the field to where Wither wafted poetically beneath the leaves of a sycamore tree.

“Humphrey, you look like you’ve found a cupcake and dropped it.”

I explained how the ghost children refused to help, and about how they hated me because I’d bumped them.

“What you must do,” Wither said, “is return to Ghost School and move the children to tears with a heartfelt speech. The children will flock to your cause like moths to a flame.”

“I’m no good with words, Wither.”

“I’ll wisp back to the house,” Wither said,

chewing a wasp, “and write a speech on the clicky-clacky typewriter.”

“If you don’t mind, I’d rather make it up as I go along.”

Together we floated across the field, higher this time, so high that the sheep and trees and the Ghost School building looked like toys.

I floated down, waving my arms above my head. The children gathered around to hear what I had to say.

“I’m sorry for bumping you. I just wanted to have fun, that’s all.”

“Boo!” the children booed. “Boo! Boo!”

“Please listen,” I said. “There’s this headmaster at Still-Alive School, and he’s a bully, and, um—”

“Boo! Boo!”

“Look,” I said, “if you don’t help me, I won’t have a school to go to, and I’ll have to study at home with Wither.”

“The boring old Victorian poet?” Phil Phantom asked.

“That’s what you get for bumping us,” Samuel Spook said.

I shrugged, bit into a jelly doughnut, and wisped away.