Scribbling the Cat: Travels With an African Soldier (2 page)

Read Scribbling the Cat: Travels With an African Soldier Online

Authors: Alexandra Fuller

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #History, #Military, #General

The hangovers from these drunken confessions of titanic misery (aborted marriages, damaging madness, dead children, lost wars, unmade fortunes) last nine or ten months, during which time no one really talks about

anything,

until the pressure of all the unhappiness builds up again to breaking point and there is another storm of heartbreaking confessions.

But K, perfectly sober and in the bright light of morning,

volunteered

his demons to me, almost immediately. He hoisted them up for my inspection, like gargoyles grinning and leering from the edge of a row of pillars. And I was too curious—too amazed—to look the other way.

It bloody nearly killed me.

THE YEAR THAT I went home from Wyoming to Zambia for Christmas—the year I met K—it had been widely reported by the international press that there was a drought in the whole region. A drought that had started by eating the crops in Malawi and Zimbabwe and had gone on to inhale anything edible in Zambia and Mozambique. It was a drought that didn’t stop gorging until it fell into the sea, bloated with the dust of a good chunk of the lower half of Africa’s belly.

News teams from all around the world came to take pictures of starving Africans and in the whole of central and southern Africa they couldn’t find people more conveniently desperate—by which I mean desperate

and

close to both an international airport and a five-star hotel—than the villagers who live here. So they came with their cameras and their flak jackets and their little plastic bottles of hand sanitizer and took pictures of these villagers who were (as far as the villagers themselves were concerned) having an unusually fat year on account of unexpected and inexplicably generous local rain and the sudden, miraculous arrival of bags and bags of free food, which (in truth) they could use every year, not only when the rest of Africa suffered.

The television producers had to ask the locals—unused to international attention—to stop dancing and ululating in front of the camera. Couldn’t they try to look subdued?

“Step away from the puddles.”

Rain slashed down and filming had to stop. The sun came out and the world steamed a virile, exuberant green. The Sole Valley looked disobediently—at least from the glossy distance of videotape—like the Okavango Swamps. Women and children gleamed. Goats threatened to burst their skins. Even the donkeys managed to look fortunate and plump. In a place where it is dry for nine months at a stretch, even the slightest breath of rain can be landscape-altering and can briefly transform the people into an impression of tolerable health.

“Explain to them that this is

for their own good.

God knows, I am not doing this for

my

entertainment.”

If the television crews had wanted misery, they had only to walk a few meters off the road and into the nearest huts, where men, women, and children hang like damp chickens over long drops losing their lives through their frothing bowels. But HIV/ AIDS is its own separate documentary.

Life expectancy in this dry basin of land has just been officially reduced to thirty-three. How do you film an absence? How do you express in pictures the disappearance of almost everyone over the age of forty?

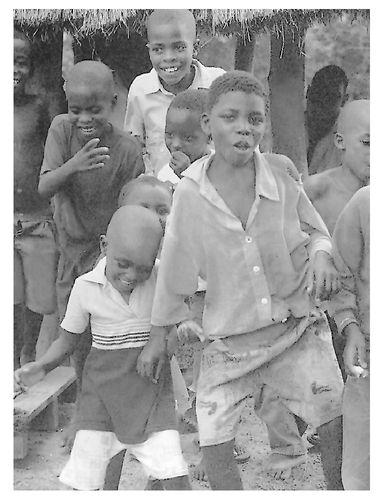

“Please ask those young boys to look hungry.”

The young boys obligingly thrust their hips at the camera and waggled pink tongues at the director.

Sole Valley children

Characteristic Malidadi Flood

Mum and dogs

I TRAINED AND IT RAINED and it rained.

Year after year—within my decade-long relationship with it anyhow—Sole had been so parched that its surface curled back like a dried tongue and exposed red, bony gums of erosion. But now—when the international news crews were finally on hand to document its supposedly dry misery—the valley had apparently grown bored of being a desert and had decided to turn itself into a long, shallow lick of lake. Where once goats and donkeys hung rib-strung over bare ground, knee-high greenery appeared. Land that once danced, dry heaving with heat waves, now sung with the deadly whine of mosquitoes. While the surrounding land began to take on the hollow-eyed aspects of a glittering desert with stunted maize and bony cattle, Sole Valley grew small tidal waves and an infestation of frogs. Anything not big or strong enough to hold its head above the water took in a lungful of liquid and died, ballooned and stinking, in ditches and ravines. Many chickens and the odd small goat, surprised by so much unaccustomed water, died from disgust.

At Mum and Dad’s fish and banana farm, eleven kilometers off the tarmac and downstream from the brothels, the biblically dead earth sprung green with a plague of luscious weeds. All day, day after day, battleship gray clouds gathered force over the Pepani Escarpment with such gravity that they threatened to oppress the sun. Insects tumbled out of the sky, with wings cracking and prickly legs. Christmas beetles shrilled. The wind picked up and tossed the leaves of the banana trees into shreds. The dogs hid their ears under their paws and looked anxious. The turkeys crouched under the wood stack and shat piles of reeking white, and the wild birds fell silent. The clouds menaced and massed.

Above my parents’ camp, where the land sloped away into mopane pans, giant African bullfrogs that had lain in a tomb of concrete-solid earth for the last nine months exploded from the ground to mate and breed and roar for a few days before sinking back into the silence of the mud. They were enormous (as big as a soup bowl), Dracula-fanged and lurid yellow-green. They had black, lumpy ridges along their backs, like a pattern of ritualized scars from a nation of warriors.

Mum and I waded up to the top of the farm to inspect the frogs. Mum had read in her

Amphibians of Central and Southern Africa

that they can live for up to twenty years. “Do you think they’re any good for eating?” she asked.

“Mum!”

Mum rolled her eyes at me. “Don’t be so squeamish, Bobo.” She prodded one of the bullfrogs with her walking stick. “Come on,” she said to it. “Hop. Let’s have a look at those thighs.”

“Mum!”

“My frog book was vague about their palatability.”

“It probably didn’t want to encourage people like you.”

But then we found an old Tonga man collecting the frogs in a reed basket.

“See,” said Mum, “you’re overreacting, Bobo. I imagine lots of people eat them.”

She asked the man if the frogs made good eating, but as she spoke no Tonga and the sekuru spoke no English, the conversation was reduced to pantomime. Mum hopping about and croaking while chomping on a fistful of fresh air and the ancient Tonga man blinking at Mum and shoving heaps of snuff at his nose, which he sneezed back at us in little toxic, black clouds. From inside the reed basket, the bullfrogs growled and hissed. Just as I was about to point out that this cultural exchange was getting all of us nowhere and some of us embarrassed, the sekuru grasped Mum’s meaning. He unfurled his reed basket, seized a bullfrog by the throat, and lunged at us with it, grinning generously and gesturing that we should have it. The bullfrog barked and bared his fangs at me.

There is not, in any of the teach-yourself books of the local languages that line the shelves of my parents’ bathroom bookshelf, the useful phrase “Thank you for your kind offer but I am a vegetarian.”

Mum, who is an extreme omnivore, took the bullfrog back to the kitchen but lost her nerve at the last moment and set it free, whereupon it leaped under the firewood pile and glared at us with a mixture of alarm and disdain for the next several days. When it eventually died—which it did behind the pantry—it swelled up to the size of a soccer ball and Mum (who is of Scottish descent

and

has lived in Africa all her life and therefore cannot, both from habit and blood, waste anything at all) said, “What a pity it’s so smelly now. It might have made an interesting lamp shade.”

MUM AND DAD don’t have a house to speak of on their fish farm, which is fine for most of the time. Usually, walls are an unnecessary barrier to what little breeze might condescend to lift off the Pepani River and swirl around our legs and shoulders as we sweat over our meals under the tamarind tree. The kitchen is a roof held up by four pillars and a half wall. The entire south side of the kitchen is taken up with a woodstove and a heap of firewood. The north side houses shelves of crockery and Mum’s shortwave radio, perpetually tuned to the BBC World Service. The east is open to stairs that lead up through the garden to the workshop and offices, down which rain cascades in what might be a picturesque waterfall if it didn’t back up into a small, greasy eyesore of a pond in the kitchen.

In this thoroughly quenching rainy season, Mum glared at the sky and said to it in a loud voice, intended for my father’s deaf ears, “My roof leaks.” And, “Can’t you see, we don’t have walls in our sitting room?” But Dad smoked his pipe in silence, absorbed in

Aquaculture Today,

apparently unaware that he was being rained upon until Mum said, “Tim, if you sit there much longer in that rain, you’ll take root.”

Then Dad folded up his magazine and said, mildly, “What’s that, Tub? Time to get to work, is it?”

So, Mum and Dad covered their heads with tents of plastic and squelched up to the ponds to give mouth-to-mouth resuscitation to their fish, which, contrary to all logic, do not seem to like rain. And after lunch (a meal that consisted of several pots of tea and a banana) Mum and Dad trooped down to the end of the farm (shrinking hourly, as chunks of real estate were torn off by the powerful current and swept off down the Pepani to Mozambique) and stood dismal and worried on the riverbank, anxiously looking upstream, toward the brothels and taverns that make up the heart of the town of Sole. Clearly, if the rain kept up, we’d soon be knee-deep in waterlogged prostitutes and drunk truckers.

Day after day I kept to the shelter of the tamarind tree, in the company of the more sensible dogs, and drank cup after cup of tea. I read my way forward and backward through Mum’s library and watched the sky for signs of the sun setting (however camouflaged by clouds) so that I might be excused the quick dash through the rain to the kitchen for a change of diet from tea to beer.

This kept up for five days. Finally, on the fifth evening, when the sun had wrapped up the day and folded it into the Pepani Escarpment for the night, we decided that the misery of our own company could not be endured for another moment. The rain had, for the time being, cleared off, so we drove out of camp to find a dry place to drink a cold beer.

MALIDADI LODGE IS THE sort of place that is more comfortable for its familiarity than for its amenities. Dogs curl up on the floor of the thatched open-air rondavel that houses the bar and a few metal picnic tables. The lights in the bar are un-apologetically bright and thousands of insects dash themselves to death on the naked bulbs before sinking into the bar patrons’ hair, glasses of beer, and clothes (a cleavage is a liability in this climate). The formal dining room is a lozenge-shaped room painted Strepsil green. It is a room dominated by a massive satellite television and half a dozen stark tables. Less lively by far than any of the other taverns we pass to get to the lodge, Malidadi is a quiet, gently dissolving drinking hole mostly frequented by the tavern owners up the road (who are exhausted by their own noisy establishments) and by customs officials, businessmen, the local chief and his entourage, policemen, and commercial fishing guides.

On this night we—my parents and I—swelled the clientele of the bar by double (the other clients being the family of three that own the place).

I kissed everyone hello. Alex, the father, had just returned from the dead (by way of the Italian mission hospital) after a dose of particularly savage malaria. Marie, his wife, had given up smoking five or six years before, but she had smoked with such ferocity until then that she was still a pale shade of nicotine yellow and she was as fragile as a shard of ancient ivory. Katherine, the willow-thin daughter, pale and beautiful in a tragic, undernourished way, had been divorced for some years and she swallowed down her bitterness with repeated, tall glasses of neat vodka. They were generous people, made brittle with heat and disease.