Scribbling the Cat: Travels With an African Soldier (4 page)

Read Scribbling the Cat: Travels With an African Soldier Online

Authors: Alexandra Fuller

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #History, #Military, #General

I nodded.

“What do you think that is?”

I shook my head and reclaimed my finger. “Putsis?” I ventured, thinking of the eggs laid under the skin by flies in the rainy season that emerge later as erupting maggots.

K shook his head and pressed his lips together victoriously. “No.”

“Worms?”

“Wrong again,” said K.

“Pimple,” I said. “I don’t know. Boil, welt, carbuncle, locust.”

K stared at me unsmiling, like a teacher waiting for an errant student to settle down before delivering the lesson of the day. He said, “It was a couple of years ago. I had just rescued this kitten—it was the rainy season and you know how these poor bloody kittens just wash up on the side of the road like drowned rats? Well, I found this kitten and brought it home and about a week later, these bumps start appearing everywhere. I thought I’d caught worms off the kitten, so I ate pawpaw seeds. No result. So I tried deworming pills Nothing. Except I got the trots. So then I soaked both of us in dog dip and I bloody nearly killed the poor kitten, but these lumps were still hassling me. They were here”—K pointed to his face—“and here”—he clamped his hand behind his leg—“and here”—he held up his feet—“and here”—he lifted up his shirt and showed me his torso. “So then I bathed in twenty liters of paraffin and my ears bled for a month but still, these lumps kept twitching. I was going

benzi,

I tell you. Then I injected myself twice a day, every day for a week, with sheep dip, two cc’s at a time. I thought maybe I had sheep maggots under my skin. But no. The sheep dip nearly killed me, I was in bed for a week, but the bloody things kept wiggling under my skin. So I burned my mattress, boiled my clothes, fumigated my bedroom, and cooked my shoes, but still, there they were. These hard, moving lumps under my skin. I finally went to the doctor and he gave me tablets that are supposed to kill worms that these people in West Africa get. I said to the doctor, ‘This is Zambia, not bloody West Africa.’ Six pills a day. They made me so sick, I thought I was going to die. There I was, back in bed, sick as a dog, with twitching lumps. Eventually, I went to a Chinese doctor in Lusaka, Mrs. Ho Ling—she diagnosed me with having inflamed nerve endings.”

I could think of no better response than “Oh.”

“It was just nerves,” K told me, “too much stress. Too much war.”

I assumed he meant The War—which around here would mean the second chimurenga, the Rhodesian War. I said, “But that’s been over for twenty years.”

K looked at me with surprise. “Oh no, I don’t mean the hondo”—he used the Shona word for “war.” “I mean the war with the wife. No, I don’t think the hondo messed me up anything like the war with the wife did.”

K poured himself more tea and started to talk in a tireless, arbitrary manner—about God, and war and divorce—as if a vast jumble of ideas surrounding his dissolving marriage and the nature of God and the state of the universe had been stored up for months in his mind, awaiting a patient audience. The thoughts were coming raw, unfiltered, and untested, directly from K’s mind. He was like a lonely drunk who washes up to the bar after months without company and spills his soul to a complete stranger. Except that K was entirely sober.

While K talked, I studied his body. He was the kind of man whose body told as many stories as his mouth ever could. To begin with, there was the question of his hairlessness; his arms and legs looked as if they had been subjected to hours of waxing. Then, there were a number of scars to contemplate: a sliced head, some light cuts on his arm, a decorously scarred knee, and a round scar on the fleshy part of his calf that, if it was related to a similar scar above his ankle, was almost certainly the entry wound of a bullet. And finally, there were tattoos to consider, barely visible on his tawny-colored skin. On his left forearm he had a cupid (but it had been badly drawn and could also have been interpreted as a set of buttocks suspended between two billowing clouds). Above that, there was a portrait of a Viking. On his right forearm was a winged-sword symbol, like something that has been copied off a coat of arms. Above that, the words “A POS” had been written. The only men I know who have found it practical or necessary to have their blood group indelibly scratched into their limbs in blue ink have been soldiers in African wars.

So when K’s torrent of unstrained observations and ideas had slowed to a halting trickle, I said, “Selous Scouts?” because even twenty years after the end of the second chimurenga, K had the build and attitude of a soldier from Rhodesia’s most infamous, if not elite, unit.

K startled. For a moment I thought he was going to deny it but then he said, “Is it that obvious?”

“Oh no,” I lied.

“No, not the Scouts,” said K. “RLI. Rhodesian Light Infantry. Thirteen Troop.”

The RLI had been Rhodesia’s only all-white unit, highly trained white boys whose “kill ratio” and violent reputation were a source of pride for most white Rhodesians. Their neurotically graded system of racial classification apparently gave the Rhodesians a need to believe in white superiority in all things, even the ability to kill. During the worst years of the war, a quarter to a third of RLI members had been foreigners covertly recruited from Britain, West Germany, the United States, Canada, Australia, France, Belgium, New Zealand, and South Africa in a desperate attempt to ensure the unit remained lily-white.

K said, “I passed the selection course for the Scouts, but it wasn’t my scene. I stuck with the troopies. ‘The Incredibles.’ ”

“Oh?”

“I’m a hunter,” K explained. “We did the hunting, we found the gooks. We had to sniff them out.” K rubbed his knee as if an old injury had begun to twinge with the memory of combat. “Five years in Mozambique,” he said. Then he added, “Of course by the end of the war, the RLI weren’t hunters anymore. They were just killing machines—but by then I was out of it. I missed Operation Fireforce by about a year. You know, when ous were flown in and dropped on top of gooks for an almighty dustup—four, five times a day. Thankfully, I was out of it by then.”

“How was the selection course?”

“For the Scouts, you mean?”

I nodded.

“You know what they called that training camp for the Scouts?”

I shook my head.

“Wasa Wasa. In Shona wasa wafara means, ‘Those who die, die.’ ”

“So it was tough.”

K shook his head. “Not so bad. They left four of us on an island in the middle of the lake for a couple of weeks. I’ve done worse. You weren’t allowed anything except a shirt and a pair of shorts. When we got hungry enough we chased a baboon into the lake and drowned it.”

“How’d that taste?”

K considered. “Well, if I had to do it all over again, I’d cook the fucking thing first.”

“Ha.”

Then K said, “Was it this?” He put his hand over the sword-symbol tattoo.

“Perhaps,” I said.

K’s voice sank. “This is the sign for the paraquedistas.”

“For the what?”

“The Portuguese paratroopers,” said K. “The Pork-and-Cheese jumpers, we used to call them. I tracked for them a few times.”

“Portuguese from Portugal?”

K’s chin gave an abrupt pop backward, which I took as a gesture of the affirmative.

“Were they good soldiers?” I asked.

“Yes, they were good. They could shoot straight. They had a pretty good kill ratio.”

I took cover behind my teacup and said, “So did the RLI. Didn’t they?”

K threw the dogs off his lap and dusted his hands. I thought he might get up and leave now.

Instead K said, “Ja, not bad.” He leaned forward, fixed me in his lionlike gaze, and added in a soft voice, “Look, the life I’ve lived . . . shit, I wouldn’t be here . . .

you

might not be here—a lot of people might not be here—if I, if we, couldn’t slot people faster than they could slot us. I was good at what I did. . . . It was my job. I did it.”

And then to my alarm I saw tears swell and tremble on the brims of K’s eyelids. His nose grew pale-rimmed and tight.

“I’m sorry,” I said.

K threw back his head. Two lines of tears were sliding freely down his cheeks.

I poured him some more tea and shoved the cup toward him. “Here, drink this.”

K only stared into the branches of the tamarind tree. Tears had found their way into the dark folds on his neck, so that they shone in purple creases. Then K gave himself a little shake and wiped his face with the flattened palm of his hands, a gesture that I think of as being very African, the gesture of people who are not accustomed to the conveniences of napkins or towels. K sucked air in over his teeth and said, his voice watery, “It’s a good thing the Almighty forgives all of us. It doesn’t matter”—now he leaned forward and fresh tears sprung—“how much of a shit you are, how much you’ve destroyed. . . . The Almighty forgives us. He holds us all in His hands.” K took a moment to compose himself before he could continue. “I just thank Him,” he said finally.

And after that, a silence that might have been visible from space stretched in front of K and me. It was a splintering silence full of all the things I thought I already knew about K and all the things he thought I thought I knew about him.

“Anyway,” he said. “That’s all old news now, hey? The war’s over. Best we forget about it. Dead and buried.”

“Right,” I said.

“I’m sorry you had to listen to me.” He gave an embarrassed laugh. “I didn’t mean to . . . No one comes out to my farm, so I don’t see women very often. I mean white women. It catches me off guard.”

“Don’t apologize.”

K stood up and tugged the end of his shorts, “Ja

.

Well, I should probably head back to the farm and see what those Einsteins have been up to in my absence.”

By now, it was early afternoon. It was the slow part of day when heat gathers like fingering thieves into your body and steals energy and desire and initiative.

I stood up. “I imagine Dad’s still down at the fish tanks if you wanted to see him.”

“No.” K stretched. “I didn’t come to see your dad in particular. Just a white face in general. Any white face will do.” He smiled. “Mission accomplished.”

I trailed up the steps to the arch after K. The dogs, who were belly-up on the chairs or splayed out on the lawn, watched us leave the camp—they did not move. Anything with a brain and with any feeling at all was staying as still as it could. Only the flies spun and buzzed and twirled and dive-bombed.

“You must come out and see me on my farm sometime,” said K as he climbed into his pickup. “How long are you out here for?”

“I go back to the States the week after Christmas,” I said.

“Well, then there’s plenty of time. Come and see my bananas.”

I nodded. “Maybe,” I said, but my voice was drowned out by the revving engine.

K gave a dismissive wave and turned his attention to the road.

I watched the pickup back out of the yard and, in a paste of mud, grind up the slick driveway. Mud splattered the side of the vehicle and flew out behind the back wheels in little red pellets. A cascade of egrets, rattled by the commotion, erupted up out of the green grass and banked around to the fish ponds above the camp, their wings paper-white against gray clouds.

Words and War

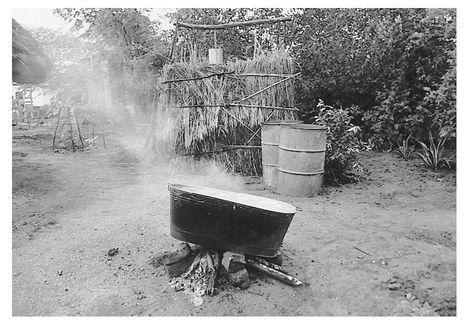

Mum and Dad ’s shower and bath

WHEN I WAS A LITTLE GIRL, spinning around in the cycle of violence that I understood, only very vaguely, as Rhodesia’s war of independence, I used to have a recurring dream that I was being abducted by a massive crow; it scooped me up from the garden where I had been playing and flew with me to Mozambique, where it dropped me on a land mine. And then I would wake up screaming, still floating toward the mine (absurdly slowly, because it was the mid-1970s and I was, at the time, fond of a pair of large hand-me-down bell-bottom jeans, which served the dual purpose, in my dream at least, of fashion statement and parachute).

The night after I first met K, I had that same old war dream and I woke up, choking on a scream, bell-bottoms billowing by my ears and the tinny taste of helplessness (the taste that comes before a scream) in my mouth. I lay in the darkness feeling my heart smack against the edge of my ribs until, at last, thinking I would not be able to get back to sleep, I let myself out of my mosquito net and into the insect-creaking night beyond its lacy comfort. I felt my way down the uneven steps (toes curled against frogs and centipedes) and toward the picnic table, which lurked shadowy and indistinct under the deep-forever night that leaked through the branches of the tamarind tree.

The rain, as Dad had predicted, had stopped by now and left the air a little cooler. Where the clouds had ragged apart, the sky reached back until the beginning of time, black poured on black. I groped around the picnic table for Dad’s cigarettes and scraped a chair back. One of Mum’s guinea fowls purred at me from its perch as I sat down.

“Just don’t take me to Mozambique,” I told the guinea fowl, blowing a funnel of blue smoke at it.

The guinea fowl spluttered and the wind gave a breathy sigh. Raindrops shook off the leaves of the tamarind tree and plopped onto my shoulders and bare legs. I shivered and pulled one of the little dogs onto my lap.