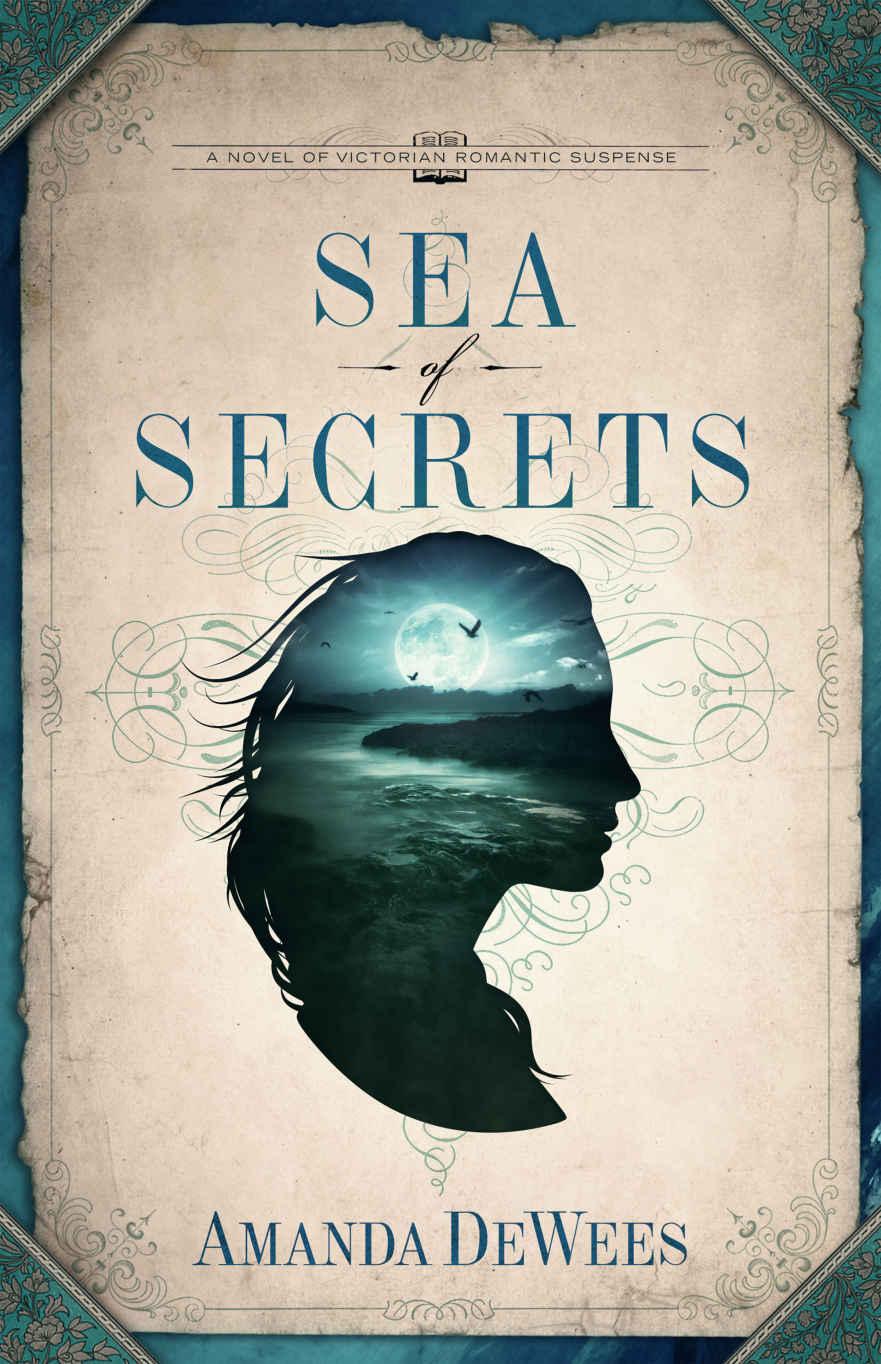

Sea of Secrets: A Novel of Victorian Romantic Suspense

Read Sea of Secrets: A Novel of Victorian Romantic Suspense Online

Authors: Amanda DeWees

Copyright © 2012 Amanda DeWees

Synopsis:

In Victorian England, innocent young Oriel Pembroke is disowned by her cruel father and takes refuge with the aristocratic Ellsworth family at their seaside estate. But as she falls in love with the brooding young duke, Herron, she begins to fear for his sanity—and for both their lives—as sinister events unfold.

After the funeral we returned to the house. We sat in the parlor listening to the drumming of rain against the windows until Father strode to the drapes and jerked them closed as if slamming the door on an eavesdropper.

It had rained all through the funeral. Not the gentle trickle that a sentimental person could interpret as tears from a sympathetic Nature; this was a soaking, squelching rain, the kind that gets under collars and into boots and eyes. Nor was it some special manifestation for the funeral; it had been raining like this all month. My brother Lionel, who had never troubled to guard his speech around me, would have said that it was pissing down.

It was Lionel we had buried today.

Because of the filthy weather the minister had rushed through the service, and the few mourners willing to brave the downpour at the graveside shook our hands quickly and damply before slogging off to their waiting carriages. Their hasty words of consolation were as grey and comfortless as the weather.

“You may be proud that he died a hero’s death,” intoned Abel Crowley, one of my father’s colleagues.

“Indeed; a bullet in the head at twenty-three is far more gratifying than pneumonia at seventy,” returned Father, and Crowley, a man not highly attuned to sarcasm, nodded sagely and clapped my father on the back before ambling away. Mrs. Merridew, the pastor’s wife, was the next to say the wrong thing.

“He is strolling the streets of heaven now, and is one with the angels above,” she quavered, all three of her chins trembling with emotion. I smothered a hysterical giggle in my handkerchief. If Mrs. Merridew had set eyes on Lionel since the day of his baptism, she would have known that he would most likely not have been admitted into heaven at all. As much as I loved Lionel, I was well aware that he was more likely to be throwing dice in a warmer clime. If by some oversight he had been admitted into the Elysian Fields, he was probably wishing he were at a dog race instead.

My father, a partisan of evolutionary theory, attended church only for the sake of appearances, so that his law practice would not suffer from his views. He gave the good lady a level look of scorn, which she was fortunately too nearsighted to catch.

But it was left to Mrs. Armadale from down the street to make the most foolish attempt to console my father for his loss.

“At least you still have your daughter,” she said.

Father stiffened. I kept my eyes lowered, but I could sense the withering glance he directed at me.

“Madam,” said Father, in his deep, solemn voice, “you cannot imagine how that fact has cheered me.”

* * *

Now I sat in a chair as near the fire as I dared, spreading out my rain-sodden skirts to try to dry them. Father stood on the hearth, feet planted wide, staring into the flames. It was one of his favorite positions: it both established his mastery and effectively blocked any of the fire’s warmth from reaching me. He was a handsome man, and created an imposing picture in his mourning black, which contrasted with his silver hair and moustache. He wore no beard, perhaps because one would have hidden his strong jaw.

He rang for tea, and Molly, the housemaid, brought it in. My hands were still stiff with cold from our vigil in the graveyard, and when I poured, tea slopped into the saucer. My father watched me with a derisive twist to his mouth.

“Such is my consolation,” he said drily. “My brave, handsome son is killed in battle, and my blundering, useless daughter remains to cheer me. How comforting it will be during the decades to come that you will always be here with me. Every day, every hour I will have the solace of seeing your face and being reminded that, while I have lost my son, I will never lose my daughter.”

I cleaned up the spilled tea as best I could and handed him his cup without answering. I had learned years ago that it was safest to say as little to Father as possible. Consequently, he added dullness to the list of my shortcomings.

Not least of these was my plainness. A daughter with dimples and glossy gold ringlets might have won his approval, even a smattering of affection. Since, however, I was from my earliest days small, thin, and drab, with no natural vivacity to lend any semblance of beauty, my father dismissed me as a financial burden and an inconvenience; sometimes, in a temper, he would go further and call me far worse.

I learned very early in life just what he thought of me. I remember being six years old and practicing at the pianoforte when he abruptly appeared at the door.

“Cease that blasted noise, girl,” he snapped. “I am attempting to get some work done.”

My instructress fluttered to him with an anxious smile. “Miss Pembroke must practice, sir, if she is to be musical.”

“Your optimism does you credit, Miss Dalby.” He regarded me with the cool calculation I know so well. He is a tall man, and at that time he seemed to tower over me, his deep-set eyes glaring out from under the strong silver brows. “She has no talent to foster; your lessons these few months have made that fact amply plain. I had hoped that, since the girl is utterly lacking in looks or charm, she might at least be accomplished, but it seems I am to be denied even this feeble compensation. I am saddled for the rest of my life with an unmarriageable brat who cannot even provide an evening’s entertainment in exchange for her room and board.” He turned swiftly to Miss Dalby, whose eyes were as wide in shock as was her mouth. “Madam, I see no reason to retain your services. Good day.”

The pianoforte was removed the next afternoon.

Now, not wishing to attract more rancor, I poured a cup of tea for myself and rose to take it to my room.

“Sit down,” he said without looking at me. “You are perfectly aware that we must be at home to condoling callers for the rest of the day. For once it is in your power to do something helpful, and you will not leave me to receive them alone.”

“Yes, Father.” I sometimes thought of myself as being one of the students in a Socratic dialogue when I spoke with Father. To whatever he said, however caustic or cruel, I answered only Yes, Father; As you say, Father; To be sure, Father. I wondered if Socrates’ students, like me, had entertained secret longings to reply, “What rubbish, Socrates”; “You’re a hypocritical tyrant, Socrates.”

Father glanced at me sharply. “And stop grinning, girl. You look completely witless.”

I erased the smile from my face. “I beg your pardon, Father.”

“What you can find to smile about on the day you bury your brother, I cannot fathom.”

That smarted, as he knew it would. Lionel had been the dearest person on earth to me, and the only one to have shown me any affection.

Our closeness did not arise from any likeness to each other; indeed, we resembled each other scarcely at all. He possessed all the blond good looks and appealing manner that I did not, and seemed incapable of being unhappy for a more sustained period than a quarter of an hour, while I have always, due perhaps to the difference in our upbringing, been inclined to seriousness. Although I found his unflappable buoyancy endearing, it could also be exasperating. Our fondness for each other was mixed on both sides with a sense of condescension: he found my gravity endlessly amusing, while I shook my head at his genial lack of understanding and his sometimes disreputable escapades. Not through malice, but through a lack of forethought, he seemed constantly embroiled in some scrape, from getting a housemaid in trouble to losing his horse in a card game—which two events he considered to be about equally trivial.

It was in the same spirit of thoughtlessness that he went to the Crimea to fight. That was the only time I ever saw Father angry with Lionel. My brother’s disastrous encounters with cards, drink, and women were met with an indulgent smile, but this was one exploit my father protested.

“I’ll not have you going off and getting yourself killed,” he boomed. “Leave that to the fools who won’t be missed. I won’t tolerate my son and heir getting his young head blown off, or rotting of malaria in some army hospital.”

“Surely there are more alternatives than the two.” I could hear the smile in my brother’s voice from where I sat sewing in the room next to the study in which they wrangled. I could envision Lionel lounging in an armchair, stroking the luxuriant golden moustache he took such pride in. He fostered that moustache as tenderly as a mother would her firstborn.

“My boy, you are too important to risk your life in this offhand manner. You are young, handsome, brilliant”—only Father would have applied this adjective to Lionel—“and need only reach out your hand for the best the world can offer. Everything you want is yours for the taking—so why choose this?”

I could hear him shift uncomfortably in the armchair, his spurs jingling. “To tell the truth, Pater, I’m bored. There’s not much to do ’round here, and I’d love the chance to be in some real fighting. You needn’t worry so; you know I’m a crack shot. I shall return heaped with laurels.”

“And if you do not return?”—grimly. “What is to become of the Pembroke line then? And of your father?”

“Dash it, it’s not as if you’d be all alone. The Mouse will be here to look after you. Besides, she’ll be married one of these days and you’ll be looking forward to whole battalions of new heirs to bounce on your knee.”

There was a pause, while my father probably entertained that possibility and assessed it.

“My boy,” he said finally, “I consider myself to be an enlightened man, and I hesitate to stake my confidence in miracles.”

In spite of Father’s protests, Lionel had left within a fortnight, bidding us farewell with a jaunty grin and a demand for letters, which he agreed to consider replying to.

“And you, Mouse,” he said to me, “must promise to be careful while I’m gone. Any day young bucks will be thronging around you, and they may just try to take advantage of my absence. Until I come back to defend your honor—”

“Lionel, really.”

“—I want to know that you won’t let yourself be won over by any smooth-tongued young blade.”

I laughed; the prospect was so ridiculous that I could only marvel at his serious tone. It was typical of him to be oblivious to the fact that I had never been sought out by so much as one shy curate, let alone a succession of scheming seducers. “Lionel, I don’t think you need worry about that.”

“But I do worry,” he said, sounding so earnest that I wanted to hug him. For all his two years’ advantage, I frequently felt as if I were much older than my brother.

“I think I have enough sense to tell a cad from a gentleman,” I said, to soothe him.

“The trouble is, so many gentlemen are cads,” he said doubtfully. But he let himself be coaxed out of his worries, and it was only as he swung himself into the waiting hansom that I felt regret that I hadn’t continued the argument and thus delayed his departure a few minutes more.