Secret, The

the Secret

the Secret

BEVERLY

LEWIS

The Secret

Copyright © 2009

Beverly M. Lewis

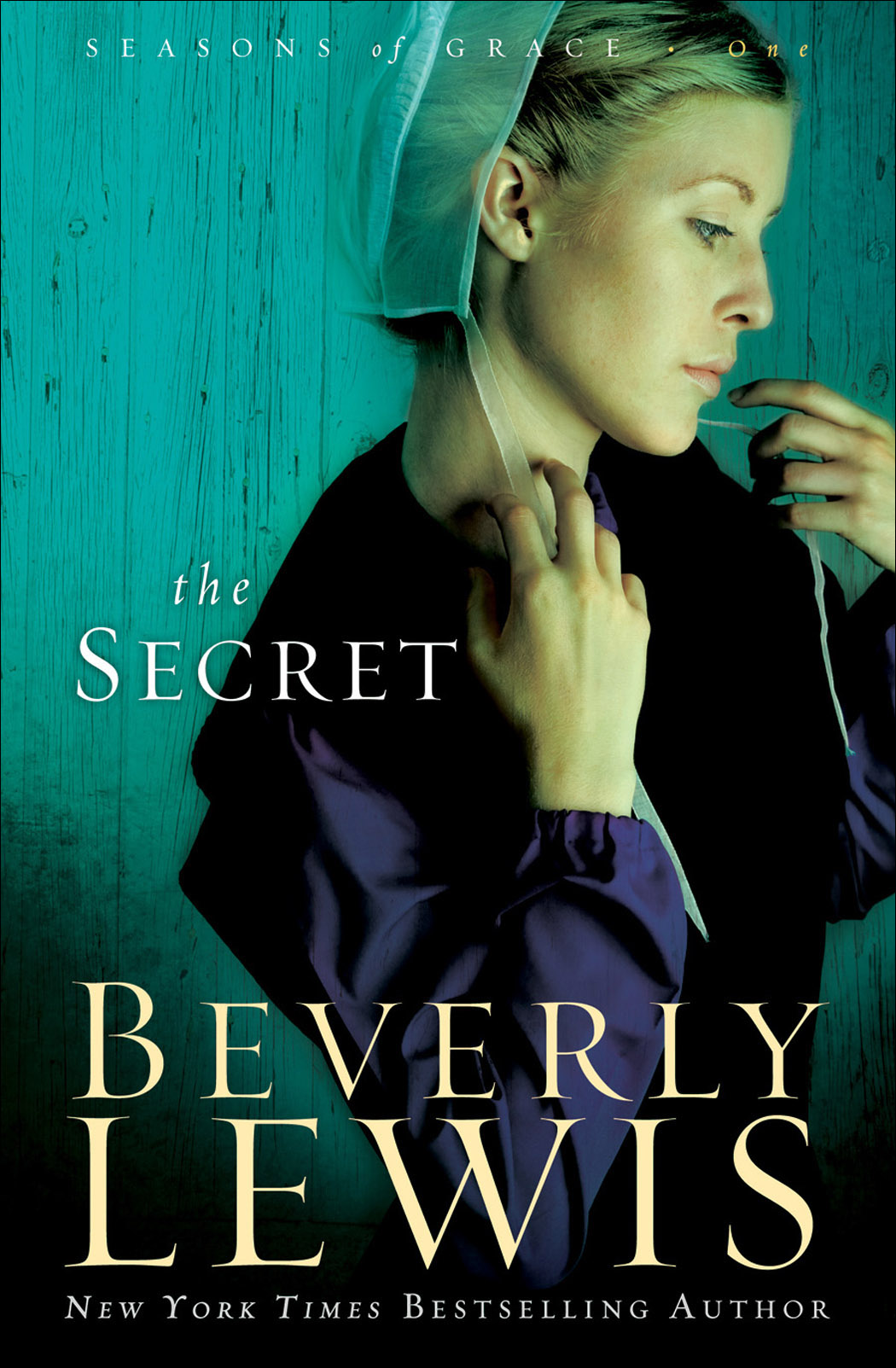

Art direction by Paul Higdon

Cover design by Dan Thornberg, Design Source Creative Services

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews.

Published by Bethany House Publishers

11400 Hampshire Avenue South

Bloomington, Minnesota 55438

Bethany House Publishers is a division of

Baker Publishing Group, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Printed in the United States of America

___________________________________________________________________________________

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lewis, Beverly.

The secret / Beverly Lewis.

p. cm. — (Seasons of grace ; 1)

ISBN 978-0-7642-0680-1 (alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-7642-0571-2 (pbk.) —ISBN 978-0-7642-0681-8 (large-print pbk.)

1. Amish—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3562.E9383S43 2009

813'.54—dc22

2008051051

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

For

Judith Lovold,

devoted reader and friend.

By Beverly Lewis

T

HE

H

ERITAGE

OF L

ANCASTER

C

OUNTY

The Shunning • The Confession • The Reckoning

A

BRAM’S

D

AUGHTERS

The Covenant • The Betrayal • The Sacrific

The Prodigal • The Revelation

A

NNIE’S

P

EOPLE

The Preacher’s Daughter • The Englisher • The Brethren

T

HE

C

OURTSHIP

OF N

ELLIE

F

ISHER

The Parting • The Forbidden • The Longing

S

EASONS

OF G

RACE

The Secret

The Postcard • The Crossroad

The Redemption of Sarah Cain

October Song • Sanctuary

*

• The Sunroom

The Beverly Lewis Amish Heritage Cookbook

*

with David Lewis

BEVERLY LEWIS, born in the heart of Pennsylvania Dutch country, is

The New York Times

bestselling author of more than eighty books. Her stories have been published in nine languages worldwide. A keen interest in her mother’s Plain heritage has inspired Beverly to write many Amish-related novels, beginning with

The Shunning,

which has sold more than one million copies.

The Brethren

was honored with a 2007 Christy Award.

Beverly lives with her husband, David, in Colorado.

Contents

SPRING

H

onestly, I thought the worst was past.

A full month has come and gone since the day of that chilly barn raising southeast of Strasburg. Mamma and I had traveled all that way, taking a hamper of food to help feed the men building the new barn. The plea to lend a hand had traveled along the Amish grapevine, which some said spread word faster than radio news.

There we were, sitting at the table with the other womenfolk, when Mamma let out a little gasp, jumped up, and rushed over to greet a woman I’d never seen in my life.

Then if she and that stranger didn’t go off walking together for the longest time, just up and left without a word to me or anyone.

From then on my mother seemed preoccupied . . . even

fer

hoodled.

Most worrisome of all, she began rising and wandering outside in the middle of the night. Sometimes I would see her cutting through the cornfield, always going in the same direction until she disappeared from view. She leaned forward as if shouldering the weight of the world.

Here lately, though—in the past few days—she had begun to settle down some, cooking and cleaning and doing a bit of needlework. I’d even noticed her wearing an occasional smile, a sweet softness in her face once again.

But lo and behold, last night, when talk of my twenty-first birthday came up, silent tears streamed down her ivory face while she rinsed and stacked the dishes. My heart sank like a stone. “Mamma . . . what is it?”

She merely shrugged and I kept drying, squelching the flood of questions throbbing in my head.

Then today, while carrying a thermos of cold lemonade out to the sheep barn, I saw my older brother, Adam, over in the birthing stall with

Dat

. I heard Adam say in a low and serious voice, “Something’s botherin’

Mamm

, ain’t so?” My soon-to-be-wed brother must’ve assumed he was on equal footing, or about to be, to dare utter such a question to our father. Either that or he felt it safe to stick his neck out and speak man-to-man out there, surrounded by the musky, earthy smells, with only the sheep as witness.

I held my breath and kept myself hidden from view. A man of few words, Dat gave no immediate reply. I waited, hoping he might offer a reason for Mamma’s behavior. Surely it was something connected to the stranger at the March barn raising. For as long as I remember, Mamma has always been somewhat moody, but I was just certain something had gone off-kilter that day. She kept to herself more and more—even staying away twice from Sunday Preaching.

Jah

, there was much for me to ponder about my mother. And ponder I did.

Now, as I waited stubbornly for my father to acknowledge Adam’s question, the only sound I heard was the laboring cry of the miserable ewe, her bleats signaling a difficult delivery. I swallowed my disappointment. But I shouldn’t have been surprised that Dat made no response whatsoever. This was his way when cornered. Dat’s way in general, especially with women.

I continued to stand motionless there in the stuffy sheep barn, observing my father’s serious face, his down-turned mouth. Adam, blond and lean, knelt in the deep straw as he waited to assist the struggling ewe deliver the next wee lamb—a twin to the first one already wobbling onto its feet within moments of birth. Tenderness for my blue-eyed brother tugged at my heart. In no time, we’d be saying our good-byes, once Adam tied the knot with Henry Stahl’s sister, nineteen-year-old Priscilla. I’d happened upon them the other evening while walking to visit my good friend Becky Riehl. Of course, I’m not supposed to know they are engaged till they are “published” in the fall, several Sundays before the wedding. Frankly I cringed when I saw Priscilla riding with Adam, and I wondered how my sensible brother had fallen for the biggest

Schnuffelbox

in all of Lancaster County. Everyone knew what a busybody she was.

Now I backed away from the barn door, still gripping the thermos. Perturbed by Dat’s steadfast silence, I fled the sheep barn for the house.

Adam’s obvious apprehension—and his unanswered question—plagued me long into the night as I pitched back and forth in bed, my cotton gown all bunched up in knots. In vain, I tried to fall asleep, wanting to be wide awake for work tomorrow. After all, it would be a shame if I didn’t preserve my reputation as an industrious part-time employee at Eli’s Natural Foods. I might be especially glad for this job if I ended up a

Maidel.

Being single was a concern for any young Amishwoman. But I supposed it wasn’t the worst thing not to have a husband, even though I’d cared for Henry quite a while already. Sometimes it was just hard to tell if the feelings were mutual, perhaps because he was reticent by nature. In spite of that, he was a kind and faithful companion, and mighty

gut

at playing volleyball, too. If nothing more, I knew I could count on quiet Henry to be a devoted friend. He was as dependable as the daybreak.

Too restless to sleep, I rose and walked the length of the hallway. The dim glow from the full moon cast an eerie light at the end of the house, down where the dormers jutted out at the east end. From the window, I stared at the deserted yard below, looking for any sign of Mamma. But the road and yard were empty.

Downstairs the day clock began to chime, as if on cue. Mamma had stilled the pendulum, stopping the clock on the hour she learned her beloved sister Naomi had passed away, leaving it unwound for months. Now the brassy sound traveled up the steep staircase to my ears—twelve lingering chimes. Something about the marking of hours in the deep of night disturbed me.

I paced the hall, scooting past the narrow stairs leading to the third story, where Adam and Joe slept in two small rooms. Safely out of earshot of Mamma’s mysterious comings and goings.

Was Dat such a sound sleeper that he didn’t hear Mamma’s footsteps?

What would cause her to be so restless?

I’d asked myself a dozen times. Yet, as much as I longed to be privy to my mother’s secrets, something told me I might come to wish I never knew.

The holiest of all holidays are those

Kept by ourselves in silence and apart;

The secret anniversaries of the heart.

—Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

A

pril in Bird-in-Hand was heralded by brilliant sunrises and brisk, tingling evenings. Every thicket was alive with new greenery, and streams ran swift and clear.

Known for its fertile soil, the idyllic town nestled between the city of Lancaster on the west and the village of Intercourse to the east. In spite of the encroachment of town homes and newly developed subdivisions on nearly all sides, the fertile farmland remained as appealing to outsiders as it did to Judah Byler and his farming neighbors.

Judah’s big white clapboard house was newer than most of the farmhouses in the area. Its double chimney and sweeping gables lent an air of style to the otherwise ordinary siding and black-shuttered windows. He’d drawn up the plans twenty-some years before, situating the house on a piece of property divided from a vast parcel of pastureland owned by his father. Judah took great care to locate an ideal sloping spot on which to pour the foundation, since the house would be situated on a floodplain. Together he and his

Daed

planted a windbreak of trees and erected several martin birdhouses in the yard. His married brothers, father, and uncles had all pitched in and built the large ten-bedroom house. A house that, if cut in two, was identical on both sides.

Just after breaking ground, Judah took as his bride Lettie Esh, the prettiest girl in the church district. They’d lived with relatives for the first few months of their marriage, receiving numerous wedding gifts as they visited, until the house was completed.

Eyeing the place now, Judah was pleased the exterior paint was still good from three summers ago. He could put all of his energies into lambing this spring. It was still coat weather, and he breathed in the peppery scent of black earth this morning as he went to check on his new lambs again. He had risen numerous times in the night to make sure the ewes were nursing their babies. A newborn lamb was encouraged to nurse at will, at least as frequently as six to eight times in a twenty-four hour period.