Secrets for Secondary School Teachers (11 page)

Read Secrets for Secondary School Teachers Online

Authors: Ellen Kottler,Jeffrey A. Kottler,Cary J. Kottler

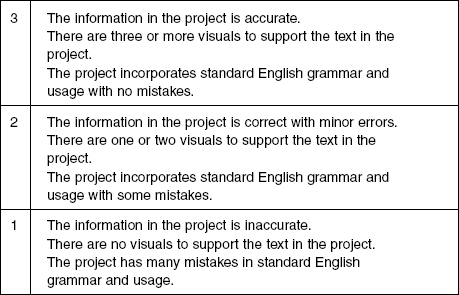

Holistic Scoring

A holistic rubric gives an overall picture by grouping together the characteristics being evaluated. A continuum of proficiency is developed from high to low and a point value assigned to each category.

Figure 6.2

is a general example of a holistic scoring guide. A score is given according to the category that best matches the quality of the work. With such a guide, students know exactly what is expected. Teachers can quickly give feedback to the students, but it tends to be general rather than specific in nature.

Analytic Scoring

Analytic scoring gives points for specific criteria. (See

Figure 6.3

.) It therefore gives more detailed feedback to the students. The criteria may or may not be grouped in categories. Points are totaled for a grade.

Introductory Activity

After your goals, essential questions, objectives, and assessments have been determined, you are ready to plan the lesson. Whether you have a traditional 45- to 55-minute period, or a block session that is longer, you will want to start with an introductory activity that is engaging and motivating. Effective introductions link to prior knowledge and stimulate the senses. You can use art, music, video, poetry, quotes, present an interesting question, or perform a brief demonstration. Movement is also important since children, much more than adults, get impatient with sitting still.

Figure 6.2

General Example of Holistic Scoring Guide

There are 3 points possible using this rubric. Additional criteria can be added to each level as desired.

Figure 6.3

General Example of Analytic Scoring Guide

There are 9 points possible using this guide. Other criteria to consider include organization, use of references, creativity, presentation, and neatness.

When I (Jeffrey) was teaching a lesson with Bushman children in Namibia, I quickly learned that anything we did together had to take place within a context of movement, whether that involved pantomime, dance, or exercise. My first thought was that in this so-called primitive culture, the children had never learned the skills of what it takes to be successful students. Then I realized that in our culture, we have actually unlearned the skills of what it takes to have fun while learning. The whole idea of learning by sitting motionless in seats while being talked to is antithetical to everything we know and understand about how learning takes places. The more active we can structure our lessons, the more likely that students will remain truly engaged.

Above all else, the introductory activity should be designed to capture student attention and set the stage for the day’s lessons. This opening activity is sometimes referred to as the “anticipatory set.” It should be followed with a statement of objectives and explanation of why this is important. Then you are ready to proceed.

Note: Many teachers begin the period with a “bellringer” or an initial “sponge” activity to get students involved as soon as the bell rings. This activity may or may not be related to the lesson of the day. A review “question of the day,” “warm-up” problem, or the copying of objectives and homework assignment, all of which are not related to the lesson and do not serve a motivating purpose, should not be considered as an introductory activity. We suggest listing these activities under the “Notes” section of the lesson plan.

Learning Activities

The body of the lesson follows. Now, you select the methods (for example, direct instruction, inquiry, or cooperative learning) and identify the corresponding activities for students, including time to practice what they have learned. Remember to consider learning styles as well as multiple intelligences in order to give students the opportunity to function in their areas of preference and strength, as well as to give exposure to and build confidence in their less-preferred and weaker areas. Some teachers try to estimate how much time each activity will take, structuring time for students to practice individually and in groups under their guidance. Include time for cleaning up material and supplies and putting books and resources away. Don’t forget to list the supplementary materials and supplies you will need in the “Materials/Resources” section of the lesson plan. With this list in hand, you will be able to gather quickly the items you need for the period. Some teachers like to list the Web sites they will access if using the Internet during class.

Adaptations and Modifications

Given the mix of students’ English language development, reading abilities, and cultural backgrounds, lessons need to be differentiated when and where it is possible to accommodate the various learners in the classroom. Moreover, reading strategies need to be incorporated into each class.

•

Special-Needs Students.

This population of students will have Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) indicating modifications and adaptations to be made for those who qualify. Some of the changes you may need to implement include the following: breaking assignments into small chunks, using graphic organizers, narrowing the focus to key terms and concepts, allowing extra time for completion of tasks, using a computer or other assistive technologies, having someone else write for them. Their assessments will have to be similarly modified. Each student will have an IEP, which will give you guidance.

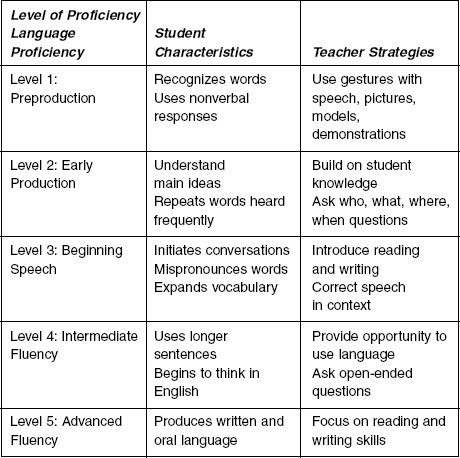

Figure 6.4

Brief Overview of Language Development Proficiency Levels and Student Characteristics With Corresponding Teacher Strategies

•

English-Language Learners.

These students present their own challenges. It may be helpful to look at the level of language ability and then design activities and assessments accordingly. A brief overview of five levels of language proficiency, characteristics of students, and a few corresponding suggested teacher strategies are found in

Figure 6.4

.

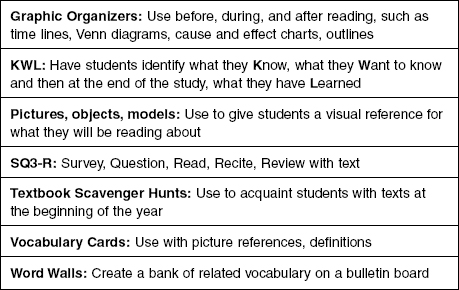

Figure 6.5

Literacy Strategies

The assessments for English-language learners will also require changes. You may decide to include a word bank and/or allow for drawings or other visual representations, outlines, or graphic organizers.

•

Grouping.

Some children enjoy working in groups, while others like to work alone. Different groupings should be facilitated. You may want to assign group members based on their diversity and learning needs or you may decide to have homogeneous groups and change group membership periodically so that all students have a chance to work with and get to know each other.

For some activities, the class may participate as a whole; for other activities, partner work may be most appropriate; and a third structure is to have students work individually. Or, you can use a combination with differentiated learning, that is, having students work on different tasks related to a given objective according to their abilities. This is an effective way of meeting the needs of all students in your class. In particular, it

provides a structure for gifted students to work on challenging content at their own pace.

Teaching Reading

With the

No Child Left Behind

emphasis on literacy, all teachers need to be responsible for developing literacy skills. The literacy strategies listed in

Figure 6.5

will help get you started.

Carefully selected supplementary reading material will often capture students’ attention and engage them on a given topic, where students often get lost in the monotony of textbooks.

Students often fail to see the practical value of what they are reading. I (Cary) remember thinking all the time, “What does this stuff have to do with anything?” or “Why will I ever need to know about this?” Well, my Government teacher had a unique solution to combat this problem. She had each of the students in her class get a subscription to Newsweek magazine. They offered a student rate so it wasn’t very expensive. Each week we were required to read the articles relating to American and world politics. We took a short quiz each Friday on how the articles related to the areas of government we were studying at the time. Not only was it more fun and interesting to read than the textbook, it also let us know what was going on in the world.

Closure

At the end of the period, take a few minutes to relate the learning activities back to the objectives. This can take place in the form of a brief summary (such as a whole-class, small-group, or partner discussion), or writing a reflection (such as a journal response in which students contemplate what they learned or experienced during the period), or a culminating activity that demonstrates mastery (such as integrating new vocabulary or performing a new skill).

Notes

At the beginning or at the end of the period, there may be various “housekeeping” activities you may want to list. Such items might include general school announcements and attendance at the beginning of the period, and directions for homework and other reminders related to your class at the end of the period.

Reflection

It is a good idea to spend some time reflecting each day after class to evaluate how the class went as compared to the plan. Some questions to ask yourself might include the following:

• How did the students respond to the introductory activity? Did they become engaged? Did it serve the inspirational or motivational purpose you intended?

• Were students able to progress successfully through the lesson? If not, what obstacles can you identify?

• How was the pacing? Too fast? Too slow? Just right?

• Were there any materials or references that should have been included?

• Were there any questions that the students asked that could have been addressed differently?