Seductive Poison

Authors: Deborah Layton

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs

DEBORAH LAYTON

Seductive Poison

Deborah Layton was born in Tooele, Utah, in 1953. She grew up in Berkeley, California, and attended high school in Yorkshire, England. After her escape from Jonestown, Guyana, in May 1978, she worked as an assistant on the trading floor for an investment banking firm in San Francisco until she resigned in 1996 to begin writing

Seductive Poison.

Layton lives in Piedmont, California, where she is raising her daughter.

For

Lauren Elizabeth,

my daughter,

who asked tough questions and gave me the strength to go

back and face the darkness

In memory of my mother, Lisa Philip Layton,

her mother before her, Anita Philip,

and

the nine hundred thirteen innocent children, teenagers, and families

who perished,

wholly deceived, in Jonestown

Contents

2.

Exiled

20.

Hope Extinguished, November 18, 1978

Foreword

CHARLES KRAUSE

In April 1978, Debbie Layton Blakey was still in Jonestown as I was taking up my new assignment for the

Washington Post

in Buenos Aires. We didn’t know each other then, nor would we meet for many years to come. Yet our lives would soon be intertwined.

That spring twenty years ago, Debbie, increasingly worried about conditions in Jonestown, was about to make a decision that would reverberate around the world; I was a young reporter intrigued by the prospect of covering wars and revolution in Latin America. Buenos Aires was my first foreign assignment after having spent five years covering local politics in the Washington suburbs.

I knew that reporting, especially from countries where leftist guerrillas were battling right-wing military governments, and where the press was often suspect, could be dangerous. But no one had ever mentioned cults—or being shot at by Americans. In fact, I think it would be safe to say that in April 1978 no one at the

Washington Post—

or probably in Washington—had ever heard of the Peoples Temple or Jonestown.

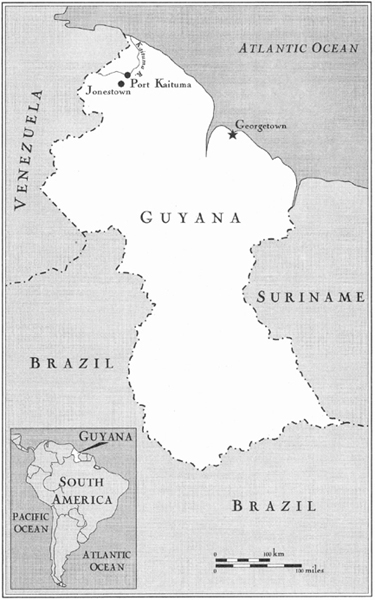

As I was en route to Buenos Aires from the United States, it is entirely possible that my Pan Am flight overflew Guyana, the former British colony turned socialist Co-operative Republic of Guyana, located—“lost” might be a better word—on the northeast bulge of South America.

I had no way of knowing that down below, Debbie Layton, her mother, and some nine hundred other Americans were living as virtual prisoners in the Guyanese rain forest; Jonestown, the Utopia they had been promised before they left San Francisco, was essentially a Potemkin village. Nor was there any way I could possibly have known that seven months after arriving in Buenos Aires, I would be shot and nearly killed because of the fateful decision Debbie would make in May 1978 to escape from Jonestown—to seek help for her mother and for the hundreds of other members of the Peoples Temple she believed were being held in the jungle camp against their will.

There were probably many things that could have triggered Jonestown’s fiery end. But, sadly, it was Debbie’s decision to escape and seek help that became the catalyst for what is still perhaps the most bizarre and tragic episode in the history of American religious movements and messianic cults—the mass suicide-murder of more than nine hundred of Jim Jones’s followers on November 18, 1978.

For weeks, Jonestown would remain front-page news, not only in the United States but around the world. Even today, I suspect there are few Americans over the age of thirty who don’t remember where they were when they first heard that more than nine hundred of their countrymen had killed themselves, having drunk Flavour-aide laced with cyanide, in a place called Jonestown.

At the time, as horrified and as fascinated as they were, it was easy for most Americans to dismiss the Peoples Temple as a bunch of “crazies”—people not like us—and to dismiss what happened in Jonestown as solely the result of religious fanaticism, or the craziness of the times, or the bizarre hold of charismatic leaders like Jim Jones and, more recently, David Koresh and Marshall Applewhite, on a particular group of ignorant, emotionally needy, confused, or simply naïve followers.

Yet Jonestown did not happen in a vacuum.

Cults and cult-like groups had begun to proliferate during the 1960s in the United States, in reaction to the profound political, social, and sexual revolutions then under way. For many Americans, especially many young Americans, the civil rights and antiwar movements provided a very real sense of liberation. Yet others could not cope with the new freedom and the consequent disintegration of family structures, institutions, and traditional values.

Drugs, sex, rock ’n’ roll, dropping in and dropping out, all became a part of the new culture. But nobody was supposed to get hurt. There weren’t supposed to be consequences. So the awful reality that hundreds of Americans—men, women, and children—had died of cyanide poisoning in the Guyanese rain forest came as a real shock, even to those enveloped in their own psychedelic haze.

Instantly, “Jonestown” entered the lexicon, an ominous warning to all those Americans who sought meaning for their lives, and “truth,” by experimenting with all manner of quasi-religious, quasi-psychological, quasi-libertarian, or quasi-authoritarian self-help movements and cults. Jonestown would demonstrate in bold relief just how dangerous these groups—and their leaders—could be.

In December 1977, when Debbie Layton arrived in Jonestown from California for the first time, she had already been a member of the Peoples Temple for nearly seven years. Indeed, she was one of Jim Jones’s favorites, a member of the inner circle. Yet it did not take her very long to conclude that Jonestown was not the idyllic refuge she and all the others had been told it was before they got there.

Just twenty-four at the time, Debbie quickly realized that she and the others had been deliberately deceived; Jonestown was essentially a concentration camp in the jungle. Unlike many Temple members, though, Debbie was clear-headed enough to recognize that Jim Jones, the man they had given their lives to and had believed in without reservation, was increasingly paranoid, psychotic, and dangerous. That process of realization led her to contemplate trying to escape, even if that meant risking her life and leaving behind her mother, terminally ill with cancer, who had herself escaped from Nazi Germany forty years before.

The parallels—and ironies—are chilling. Both Debbie and her mother, Lisa, were obviously tough and intelligent women, survivors alert to the very real dangers around them. Yet both were, initially at least, taken in by Jones, the false prophet they chose to believe and follow, just as many German Jews of Lisa’s parents’ generation were somehow deluded into thinking that Hitler would never carry out his threats against them.

Neither Debbie nor her mom was deranged. Nor were they unstable women abnormally susceptible to the appeal of a charismatic preacher/politician. People join cults unwittingly. Even reasonable, intelligent people can be fooled by demagogues, and too often, the deeper they become involved in one of these quasi-religious or quasi-political groups, the more difficult it may be to see the potential dangers. As Debbie makes clear in this memoir, both she and her mother were searching for a life with

meaning—

not unlike so many other Americans at that time and since. Except that their search led them to the Peoples Temple and Jim Jones. Having escaped from the Nazis, it was Lisa’s fate to die in Jonestown.

During the few hours I was in Jonestown, it became apparent to me that there were a variety of reasons why people had joined the Peoples Temple. For some, it was a political statement; Jones offered the promise of a socialist society free of materialism and racism at a time when such a society was particularly attractive. For others, the Temple offered religion, structure, and discipline—a way to escape the violence of the ghetto and the dead end of alcohol and drugs (which were strictly forbidden).

But Jones cleverly manipulated both his followers and public perceptions of what he and the Peoples Temple were all about, and that is the larger lesson yet to be widely understood. In both California and Guyana, the Peoples Temple was allowed to become a state within a state, enjoying the privileges, and acquiring the legitimacy, that allowed it to thrive over many years. Meanwhile, that legitimacy hid Jones’s increasing paranoia and his increasingly erratic demands for control and for power.

The First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of religion makes it very difficult, if not impossible, to investigate religious organizations, even when, as was the case with the Peoples Temple, they deliberately seek political power to shield their immoral and illicit practices from investigation. Jim Jones was a Housing Commissioner in San Francisco, courted by the mayor, the governor, and Rosalynn Carter, even while he was raping young members of his church, stealing their parents’ money, staging fake “healings” to impress the ignorant, and threatening, perhaps even murdering, those who attempted to defect from the Temple.

Jones’s appeal to the politicians may be difficult to understand now, but it was simple—and he understood it better than they did. In 1968 the Democratic National Convention and Mayor Daley had put the final nail in the coffin of old-fashioned political machines in the United States. But to win, politicians still had to campaign and get out the vote on Election Day. Jim Jones was smart enough to identify the void; in the political free-for-all that was San Francisco in the 1970s, he had the only political machine in town.

Other books

Jane Austen by Valerie Grosvenor Myer

Mrs. God by Peter Straub

When Work Is a Pleasure by Alix Bekins

The Whitsun Weddings by Philip Larkin

Fixing Justice by Halliday, Suzanne

Conceit by Mary Novik

Ulysses S. Grant by Michael Korda

On Borrowed Time by David Rosenfelt

Billionaires, Bad Boys, and Alpha Males by Kelly Favor, Locklyn Marx

The Seville Communion by Arturo Pérez-Reverte