Shadow of the Lords (40 page)

Read Shadow of the Lords Online

Authors: Simon Levack

The Aztecs lived in a world governed by religion and magic, and their rituals and auguries were in turn ordered by the calendar.

The solar year, which began in our February, was divided into eighteen twenty-day periods (often called âmonths'). Each month had its own religious observances associated with it; often these involved sacrifices, some of them human, to one or more of the many Aztec gods. At the end of the year were five âUseless Days' that were considered profoundly unlucky.

Parallel to this ran a divinatory calendar of 260 days divided into twenty groups of thirteen days (sometimes called âweeks'). The first day in the âweek' would bear the number 1 and one of twenty names â Reed, Jaguar, Eagle, Vulture, and so on. The second day would bear the number 2 and the next name in the sequence. On the fourteenth day the number would revert to 1 but the sequence of names continued seamlessly, with each combination of names and numbers repeating itself every 260 days.

A year was named after the day in the divinatory calendar on which it began. For mathematical reasons these days could bear only one of four names â Reed, Flint Knife, House and Rabbit â combined with a number from 1 to 13. This produced a cycle of fifty-two years at the beginning and end of which the solar and divinatory calendars coincided. The

Aztecs called this period a âBundle of Years'.

Aztecs called this period a âBundle of Years'.

Every day in a Bundle of Years was the product of a unique combination of year, month and date in the divinatory calendar, and so had, for the Aztecs, its own individual character and religious and magical significance.

The date on which the first chapter of this book opens is 23 December 1517; in other words, One Death, the fourteenth day of the Month of the Coming Down of Water, in the year Twelve House.

The Aztec language, Nahuatl, is not difficult to pronounce, but is burdened with spellings based on sixteenth-century Castilian. The following note should help:

| Spelling | Pronunciation |

|---|---|

| c | c as in âCecil' before e or i; k before a or o |

| ch | sh |

| x | sh |

| hu, uh | w |

| qu | k as in âkettle' before e or i; âqu' as in âquack' before a |

| tl | as in English, but where â-tl' occurs at the end of a word the âl' is hardly sounded. |

The stress always falls on the penultimate syllable.

Â

I have used as few Nahuatl words as possible and favoured clarity at the expense of strict accuracy in choosing English equivalents. Hence, for example, I have rendered

Huey Tlatoani

as âEmperor',

Cihuacoatl as

âChief Minister',

calpolli

as âparish',

octli

as âsacred wine' and

maquahuitl

as âsword', and have been similarly cavalier in choosing English replacements for most of the frequently recurring personal names. In referring to the

Emperor at the time when this story is set I have used the most familiar form of his name, Montezuma, although Motecuhzoma would be more accurate. To avoid confusion I have called the people of Mexico-Tenochtitlan âAztecs' rather than âMexicans'.

Huey Tlatoani

as âEmperor',

Cihuacoatl as

âChief Minister',

calpolli

as âparish',

octli

as âsacred wine' and

maquahuitl

as âsword', and have been similarly cavalier in choosing English replacements for most of the frequently recurring personal names. In referring to the

Emperor at the time when this story is set I have used the most familiar form of his name, Montezuma, although Motecuhzoma would be more accurate. To avoid confusion I have called the people of Mexico-Tenochtitlan âAztecs' rather than âMexicans'.

The name of the principal character in the novel, Yaotl, is pronounced âYAH-ot'.

The featherwork was the shadow of the lords and kings.

Fray Diego Durán,

Book of the Gods and Rites

Book of the Gods and Rites

Like its predecessor,

Demon of the Air,

this book is set in Central America in the early sixteenth century, shortly before the coming of the Europeans.

Demon of the Air,

this book is set in Central America in the early sixteenth century, shortly before the coming of the Europeans.

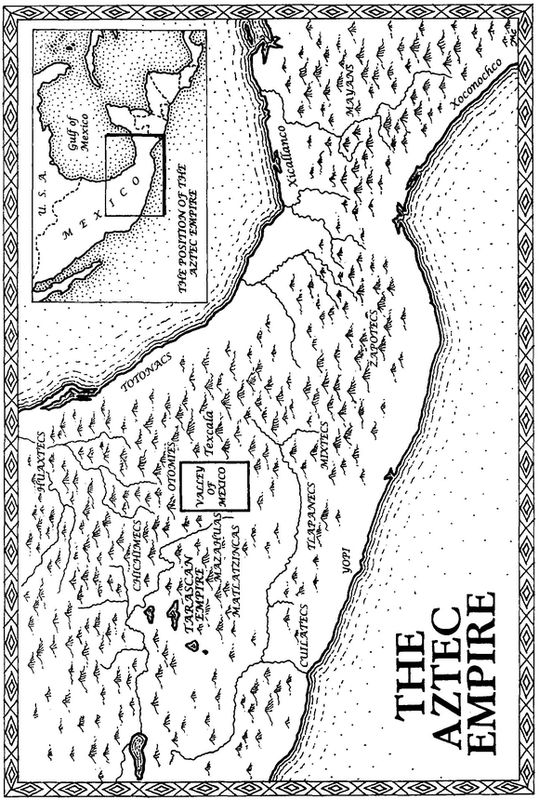

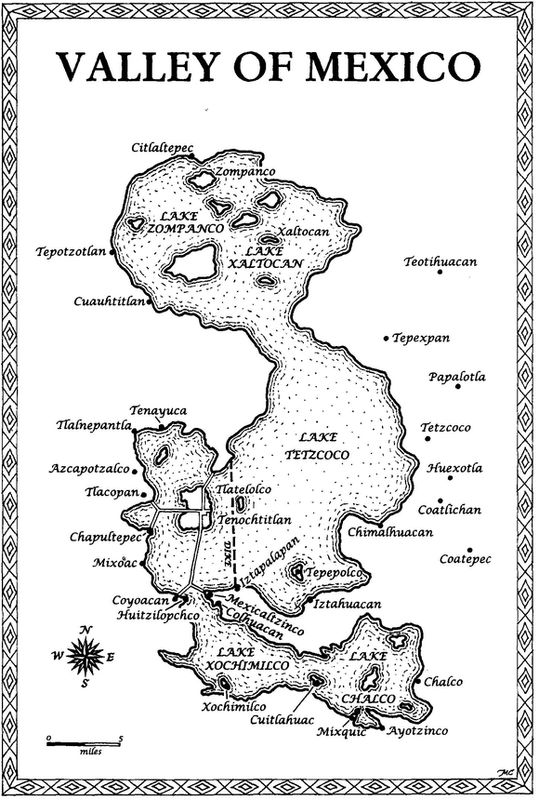

At this time the region was dominated by the warlike nation we call the Aztecs. When they first appeared at some time in the thirteenth century they were just one of a number of nomadic tribes with a common language and history, but over the next two hundred years or so they fought their way to the top. Forced to settle on a desolate, marshy island in the middle of a briny lake, they turned it into a fortress, surrounded it with fertile fields built upon artificial islands, and used it as a base from which to cow most of their neighbours into submission.

The Aztecs' own name for themselves was

Mexica;

they gave this name to the city they founded, calling it Mexico. The southern part of the city was called Tenochtitlan, and the northern part Tlatelolco. Modern Mexico City stands on the same site.

Mexica;

they gave this name to the city they founded, calling it Mexico. The southern part of the city was called Tenochtitlan, and the northern part Tlatelolco. Modern Mexico City stands on the same site.

At its zenith, under Emperor Montezuma II, Aztec Mexico

was probably the largest city in the world, outside Asia. It was the capital of an empire that stretched as far east and west as the coasts of the Caribbean and the Pacific and as far south as modern Guatemala. Like any city it was a crowded and colourful place, home to merchants, artisans, warriors, priests, lords, beggars and thieves.

was probably the largest city in the world, outside Asia. It was the capital of an empire that stretched as far east and west as the coasts of the Caribbean and the Pacific and as far south as modern Guatemala. Like any city it was a crowded and colourful place, home to merchants, artisans, warriors, priests, lords, beggars and thieves.

We are most familiar with the warriors and priests, owing to the Aztecs' notorious practice of sacrificing prisoners of war, along with other victims. Nobody writing about the period can afford to ignore them, but in this book they yield centre stage to the merchants and artisans, and in particular the practitioners of an art form with no parallel elsewhere: featherwork.

I was lucky enough to see a tiny example of the Aztec featherworkers' craft at the exhibition at London's Royal Academy between November 2002 and April 2003. Even after five hundred years, I was able to marvel at the painstaking care and exuberant sense of colour that had gone into producing it, and wonder what combination of inspiration, religious fervour and technique might have guided the maker's hand.

Some of the answers I dreamed up found their way into this novel â along, of course, with the usual mayhem â¦

Demon of the Air

SHADOW OF THE LORDS. Copyright © 2005 by Simon Levack. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address St. Martin's Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y 10010.

Â

Â

THOMAS DUNNE BOOKS.

An imprint of St. Martin's Press.

First published in Great Britain by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

Â

Â

eISBN 9781466807969

First eBook Edition : December 2011

Â

Â

Extracts from

Fifteen Poets of the Aztec World

by Miguel Leon-Portilla are reproduced by kind permission of the publishers, University of Oklahoma Press.

Fifteen Poets of the Aztec World

by Miguel Leon-Portilla are reproduced by kind permission of the publishers, University of Oklahoma Press.

Extracts from Bernadino de Sahagun,

The Florentine Codex, A General History of the Things of New Spain,

translated and edited by Arthur J. O. Anderson and Charles E. Dibble, are reproduced by kind permission of the University of Utah Press and the School of American Research.

The Florentine Codex, A General History of the Things of New Spain,

translated and edited by Arthur J. O. Anderson and Charles E. Dibble, are reproduced by kind permission of the University of Utah Press and the School of American Research.

First U.S. Edition: September 2006

Other books

Marking Time by Elizabeth Jane Howard

September: Calendar Girl Book 9 by Audrey Carlan

Like Jake and Me by Mavis Jukes

Incubi - Edward Lee.wps by phuc

Night at the Fiestas: Stories by Kirstin Valdez Quade

Working the Dead Beat by Sandra Martin

Fallen Angel: Mythic Series, Book 2 by Abbie Zanders

Firehouse by David Halberstam

In the Middle of the Night by Robert Cormier

The Wicked Wager by Anya Wylde