She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me (26 page)

Read She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me Online

Authors: Emma Brockes

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Adult, #Biography

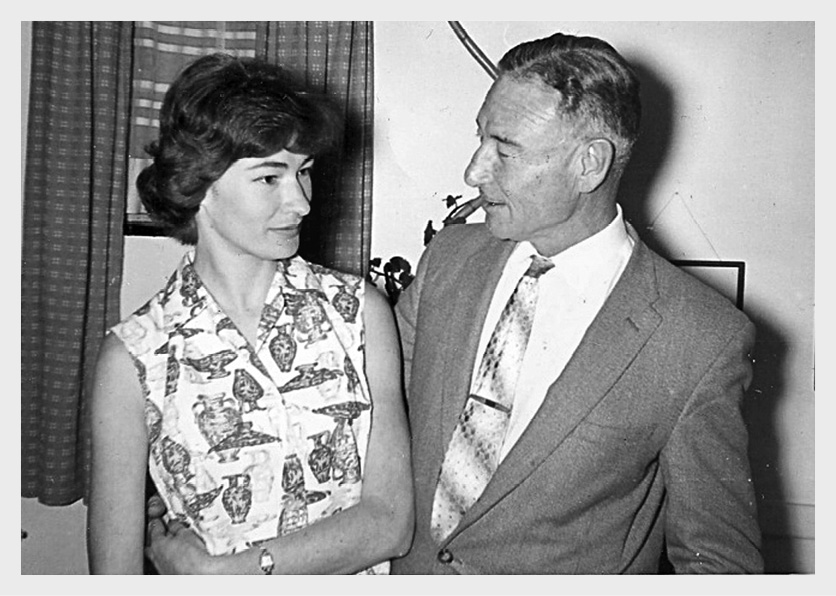

To hell with all that: my mother on the day she left South Africa for England, in November 1960.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

FAY IS HAVING A LITTLE

gathering at her house. It is not a reunion per se. Words like “reunion” put too much pressure on attendees, plus the idea of togetherness in this family is so toxic as to be almost funny. “It'd be hilarious,” said my cousin Jason while we were sitting in the garden with his mother on the coast. “We could get all of you in a room together, get in loads of booze, and invite Jerry Springer.”

“You're not big,” snapped Doreen, “and you're not clever.”

But Fay is being optimistic. Her brother Tony is coming, whom she hasn't seen for nineteen years, and Tony's ex-wife, my aunt Liz, and some of Liz's boys, plus Fay's daughter-in-law and her husband, Trevor. She invited her daughter, Victoria, whose reaction I can just imagine. Yes, says Fay, it was along the lines of “I'd rather stick pins in my eyes.”

At her round dining table, my aunt and I excitedly plan how many sandwiches we'll need. A few days later, we drive to the shopping mall to pick them up. They are dainty white triangles with their crusts taken offânot like the huge, chunky doorsteps my mother used to makeâlaid out on a large silver tray. Before everyone arrives, I take a photo of the fridge, which has been stripped of food to make way for a pyramid of beer bottles. We drag plastic chairs out onto the terrace. It's an overcast day, but we are in high spirits.

“Won't it be weird to see Tony?” I ask.

Fay giggles. “Very weird.”

“Will he and Liz be all right in the same room together?”

“Oh, yes.”

Everything flows off Fay's back. It is an attitude often mistaken for passivity, but one that I have come to understand as a Zen-like transcendence. I ask her how many years it has been since all the siblings were in a room together. She supposes it was at her mother's funeral longer than two decades ago, although “Of course, your mom wasn't there for that.” It is always Fay, the sensible one, who is called upon to break news of a death in the family. It was Fay who rang my mother with news of Mike's death, and who drove over to her own mother's house to break the same news. Marjorie had been drinking heavily for a long time by then. She came to the door, says Fay, saw her daughter's face, and said afterward, “I knew instantly. But I thought it would be Doreen.” Marjorie put a leash on the dog and went out for a long walk. When she came back, Fay says, she said good-bye and left.

Before that, she supposes, the nearest they got to a family reunion was my mother's first trip back to South Africa, in 1967, before the siblings had fully scattered to pursue their own lives. Steven had told me about this; he remembered the visit well. He remembered one incident in particular. When he told me about it, I was surprised I hadn't heard the story from my mother, since it flattered the idea she had of herself, although it was also, possibly, one of those stories she thought would set a bad example, like shooting her father. Marjorie's sister had been in town from Ladysmith, and high tea was arranged at one of the posher hotels. It was Steven's recollection that my mother reluctantly gathered those of her siblings she could lay her hands on and they all trooped along to the hotel. My mother didn't like this woman, whom she sensed had always looked down on them. She referred to her not by her name, Doreen, but as “that frowsy old cow.”

True to form, said Steven, his aunt Doreen proceeded to patronize them over sandwiches and tea. At some point in the afternoon, my mother had had enough. She suggested to her aunt that they play a little parlor game popular in England at the time. Doreen was delighted. In 1967, fashions established in the old country still held sway among those who considered themselves well-to-do in South Africa. “Yes,” said my mother, who would shout when irritated but when she wanted to do real damage would lower her voice. “It works like this: everyone goes around in a circle and says their favorite curse word. I'll start.” And summoning her pearly new accent, she looked into the eyes of her enemy and said, “Cunt.”

As Steven remembered it, the aunt actually screamed. In any case, she leaped from her seat, fled the room, and drove the five hours back to Ladysmith in one go.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

THERE WILL BE NO TEARS

or ululations at the gathering today. It is not the house style. Call it repression or call it self-discipline, but when brother and sister set eyes on each other after almost two decades, it is with mild, sardonic expressions. After a brief hug, Fay tells Tony to make himself useful and get up on a stool to change a lightbulb over the front door. Tony hops to it. I take a photo of him up there in a canary-yellow polo shirt, hands clasped together like a crumpled angel. When I get back from the kitchen, he has spotted something on the horizon. “Look at my fat wife!” yells Tony from his vantage point, as Liz struggles up the path, carrying beer. She gives him a look to stop traffic.

She has brought a friend along, George, who has a warm, likable air, hearty and male and smelling slightly of whiskey. I give my aunt a hug, and nodding at George, say, “I'm so glad you've got rid of that other awful man.” My aunt grins out of all proportion to the comment, and looking over her shoulder I see why. A man carrying a crate of beer emerges from between parked cars. I split my face in two to receive him. “Johannes! How lovely to see you.”

While Tony and Liz's sons mill about on the lawn, cradling beer bottles and chatting politely, their parents sit beside each other at the table, drinks in one hand, cigarettes in the other. Tony points to Johannes and says, “You'd better watch out, eh,” and starts going through a long list of Liz's ex-boyfriends who have one way or another come to sticky ends.

“Willem, taken by God. Andreus, taken by God,” says my uncle. Liz, smoking, looks as if at any moment she might shoot a poison dart out of the end of her cigarette and into her ex-husband's neck. “God takes away those who deserve to be punished,” says Tony, solemnly.

“Shame God didn't take you, eh,” says his ex-wife.

Tony looks martyred. “They persecute me in His name.”

“They persecute you because you're no bloody good and a drunk.”

“Shut up, woman, or I'll beat you up.” My uncle's verbal tic doesn't get any less startling. He sighs. “She left me for a better man.”

“Then what are you so big-headed about?”

My uncle grins. “It took her twenty years to find one.”

Fay turns to Liz and asks about the court case. Liz inhales deeply on her cigarette and says, “Fourteen years commuted to six.”

“What's this?” I say. Fay says blandly, “Oh, didn't I tell you?” Liz's sister was shot dead by her husband last year after he discovered she was having an affair. Sentencing was this week.

“Easy on the rum and Cokes, eh, George,” says Johannes from across the table. “I don't have a black suit for your funeral.”

“I hear you, man,” George cackles. I think, “Johannes is afraid of George, and a good thing, too.”

Johannes rubs his hands together. Someone asks after his son. “Holding up,” he says, and explains, for the benefit of the audience, that he is serving time for murder.

I look across the table at Trevor, who is not, by Fay's account, a very enlightened individual and who seems to be struggling with the novelty of finding himself the most liberal man at the party. When Johannes starts going on about how the blacks have trashed the country, how “monkeys in the tree are called branch managers now,” and how the crime rate is way up, Trevor clears his throat and, looking nervously at me, says, “There was always a lot of crime, but we didn't see it because it was in the townships.”

Tony is mostly oblivious to the wider conversation. He turns to his sister, and nodding at me, says, “I told her all about our dad.”

“It's not âdad,' it's Jimmy,” she snaps, the only time I have seen Fay lose her equilibrium.

To me, Tony says, “There was something else I meant to say to youâabout the twins.”

“What's this?” says Fay.

“Yes,” I say. “My mother spoke of them once.”

Fay turns to look at her brother.

“There were twins,” says Tony, “between Mike and me. They either miscarried or were born dead.”

Fay says, “I don't know anything about this.”

Tony says, “

Ja.

Mom had named them already. They were called Andrew and Trevor.”

Fay smiles in a kind of half-dazed embarrassment. “Well,” she says. “Well.”

There is more beer, more cigarettes. Everyone pushes their chairs back from the table and settles into them. “You'll see,” says Johannes, to one of my younger male cousins. “They say it's wrong to hit a woman. But if one hits you, it's within your rights to hospitalize her.” My cousin scowls across the table.

“That's right,” says Trevor. His wife, smoking stonily, turns to looks at him. “Not that I would,” he adds quickly.

“You're very quiet,” a cousin's wife says to me. If I had the courage, I would say it was because the afternoon seems to have turned into a meeting of wifebeaters anonymous. Because I don't understand what this is, where men can say these sorts of things at the lunch table as if it were the most normal thing in the world, while their wives frown and withstand it. Instead, I say, “I'm fine.”

Tony, on his own unique path, clears his throat. “I come from a long line of alcoholics,” he says, before everyone at the table shouts him down. When he tries to bring up the subject of the “human intestinal fluke,” an even rowdier chorus defeats him.

“She tricked me,” he says, pointing to Liz and reaching back to some distant memory from their marriage. “She said she needed to go to the doctor, so I took her there, and when we got to the surgery they stuck a needle in me and banged me up in the drying-out ward.”

“You needed it, eh.”

“Trickery. And then she drove me home even though she can't drive, and my head bashed against the dashboard.”

“You're such a liar.”

Liz turns to me. “We had nothing. We were really poor. We lived near the cemetery, and in the Indian section they leave curry out on the graves, so after they'd left we'd go and steal the food.” She knows how this sounds and smiles to acknowledge it, taking a deep drag on her cigarette. She says, “The dead can't chase you.”

Before she leaves, Liz turns her electric-blue eyes on her ex-husband. “Man, look at the hole in your trousers,” she says. Liz sighs, as if in the face of an unpleasant but irresistible force. “Give them to me and I'll mend them for you.”

My uncle looks at her tenderly. “She's been in this family as long as any of us, eh,” he says.

After everyone has left, I take a photo of the empty fridge. Fay and I sit side by side on the sofa, exhausted. Notwithstanding Johannes's various contributionsâ“Rough,” says my aunt, shuddering, “rough”âwe declare the afternoon a success. I'm not sure what criteria we're judging this by, until the next day, when Liz rings Doreen, who rings me straight afterward, giggling. “Liz said you all had a nice time yesterday,” says Doreen, and flattens her accent to do the impression. “âIt was nice, Dor,' she said. âThere were no fights and no one got drunk.'” Doreen laughs uproariously.

Fay and I agree. “It was all just so civilized.”

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

I HAVE NOT FOUND

the prosecutor. Nor the arresting officer. And there are friends of my mother's I still haven't seen. I have reached saturation point, but there is one final connection I want to explore. The person in question is dead, but she was very important to my mother. I want to know something of her.

There are four or five Sosnoviks in the Johannesburg phone book. The first one I call says with surprise, yes, he knew a Sima Sosnovik. She was his late aunt. A couple of days later, I drive to his house, a large, imposing building in one of the nicer suburbs. He is a lawyer, I think. I say hello to his wife and we repair to his study, where I repeat what I said to him over the phone; that my mother and his aunt had worked together in the 1950s; that Sima was important to her, and I'm interested in that period. I am aware that as an explanation, it doesn't quite cover it, and he looks at me oddly but is game to help. “I think your aunt was some kind of role model to her,” I say.

“Yes, well, she was a forceful character, in a quiet way,” he says. “Not a shouter, but forceful.” He tells me she was born the fourth of seven children in Bialystok, which at the time was part of the Russian empire. The family moved to South Africa in 1920, when she was ten. Her father was a teacher of religious studies. She started out as a bookkeeper in a fish shop in Melville. “I wish I had a photo for you,” he says. “She had reddish hair.”