Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher (22 page)

Read Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

With Upshaw’s words rattling around his head, Curtis tried to find a middle ground.

Privately, his thoughts were moving toward those of his Crow crew member. “As to his

being a savage: if we are to take the general definition of the word, there were no

savages in North America at the time Columbus landed, as they all had a religion,

notwithstanding statements to the contrary by the early explorers and priests,” he

wrote in a note from the field for the Morgan archives. In the published book of Volume

I, he editorialized in places, despite his promise not to revisit the many indignities.

“With advancing civilization,” Curtis wrote of the Apache, “they seem to have gathered

all the evils of our life and taken little of the good.” By contrast, the Navajo “have

been the least affected by civilizing influences,” he said in a tone that was clearly

celebratory. “The Navajo is the American Bedouin, the chief human touch in the great

plateau-desert region of our Southwest, acknowledging no superior, paying allegiance

to no king in name of chief, a keeper of flocks and herds who asks nothing of the

Government but to be unmolested in his pastoral life and the religion of his forebears.”

He scorned government agents for trying to force the mountainous Apache to become

farmers, an absurd proposition in a harsh land. “No tribe is more capable of living

on natural products.” And he did use both “primitive” and “savage,” though with the

first word it was almost always as a compliment, and the second was employed to describe

bounty hunters paid by the Mexican government to lift Apache scalps—women’s and children’s

included. In the end, the book was mostly practical and matter-of-fact. For instance,

he gave a recipe for how to make strong beer from mescal, the Apache way.

Curtis decamped to New York, to the Hotel Belmont, just across the street from Grand

Central Terminal, for the final publishing push in June of 1907. “I have the material

for the first two volumes practically in shape and will be able to turn it over to

the printers in the near future,” he wrote Morgan. The financier was still in Europe,

buying art and precious objects with his latest mistress, as a crumbling stock market

prompted urgent cables for his return to New York. In Italy, he was a walking bank.

Even in the shrine city of Assisi, Franciscan monks who had taken a vow of poverty

tried to entice Morgan to share some of his fortune on their behalf. He bought an

autograph manuscript of Beethoven’s last violin sonata (No. 10 in G Major), and focused

his freight-train gaze on a number of Botticelli paintings.

In Morgan’s absence, young Belle da Costa Greene handled correspondence and controlled

acquisitions for the library. She had moved her office to the new marble and limestone

palace, and with her active social life was a frequent subject of gossip in the papers.

“I’ve come to the conclusion that it really must be grudgingly admitted that I am

the most interesting person in New York,” she wrote, “for it’s all they seem to talk

about.” Pleaders from all levels of the arts world made frequent calls. Curtis saw

Greene in New York, and though he may have been as intoxicated as anyone in her presence,

his correspondence with her in 1907 was all business. As per their agreement, he presented

Miss Greene with the master prints and promised twenty-five copies of the first volume

at year’s end.

With the evanescent Belle Greene, with Harriman and his crowd in Manhattan, with Roosevelt

and Pinchot in Washington, with the gentlemen of the National Geographic Society and

others who put on black ties and silk gowns to look at lantern slides of Indians in

buckskin, Edward Curtis was a man without a breath of doubt—the tall, reservation-trotting,

horse-whispering westerner in his Abercrombie and Fitch. But to his few close friends,

Curtis was a different man, still not completely free of the homesteader’s shack and

the humility of foraging to make a living. He distrusted scholars in particular, and

it seemed as if everyone he encountered in academia knew he was a grade school dropout.

The exception was Professor Meany, who shared all of Curtis’s enthusiasms and none

of his insecurities. At a moment just before publication, when Curtis should have

been at his most confident, he told Meany he wondered if he was up to this task and

expressed fear, again, of ending up in debtor’s hell. The biggest educational institution

in the Northwest, the University of Washington, continued to balk at buying a subscription

for the work of its native son. The same was true of a handful of Seattle barons,

men who had made themselves wealthy in the early-century boom of one of the fastest-growing

cities in the world.

“Of late I have had little but swats from my home town and feel in a most disagreeable

mood,” Curtis wrote Meany in a lengthy, multipage rant. “Most of those who say good

things about the work would if I owed them two and a half and could not pay on the

dot kick my ass and say, ‘Get to hell out of this.’ Yes, I will try to cheer up a

bit, but when I think of some of the Seattle bunch I go mad. I am an unknown man trying

by sheer bulldog tenacity to carry through a thing so large that no one else cared

to tackle it.” Meany again assured him that time would be his ally—the ages would

remember him, even if the wealthy of his hometown would not. “The newly rich of Seattle,”

Meany wrote Curtis, “are foolish enough to neglect the chance of aiding one of the

greatest literary achievements of the century.” His advice was to ignore them, to

get back into the field as soon as possible, to “just run along and play.”

But before he could play, he had to sell at least a handful of subscriptions. In Chicago,

he visited Edward Ayers, a man of means and a founder of the city’s prestigious Field

Museum. Ayers considered himself an expert on Indians and also was the main benefactor

of the museum’s library—not a good combination, in Curtis’s experience.

The North American Indian

should have been a natural acquisition for him. But Ayers turned up his nose at the

photographer. He doubted that Curtis could break any new ground with the text; perhaps

the pictures would be diverting. And, as Curtis had heard many a time, he’d bitten

off more than he could chew. Ayers “thinks I have attempted too big a task for one

man, saying, ‘It looks to me as though you were trying to do 50 men’s work,’” Curtis

wrote Hodge. He hoped his editor could use his influence among the small circle of

museum executives to nudge the Chicago man along. Ayers was unconvinced. “After 30

years in studying this question, and the mass of literature I have read on the subject,

I am still in doubt about the value of the historical part of your work,” he wrote.

Besides that doubt, Ayers had to be concerned about the chilling effects of the Panic

of 1907. In the fall, the country appeared on the verge of collapse. Roosevelt was

perplexed. The markets continued to plummet. A global credit shortage added to the

deep freeze. Morgan steamed home, his latest acquisitions in steerage. He summoned

the richest men in the nation, Rockefellers, Fricks and Guggenheims among them, to

his library for a summit on how to save capitalism. Under the eyes of Renaissance

portraits, and facing Morgan’s mottled nose, the choreographers of great capital listened

to his plan. In order to stop the Bankers’ Panic they had to stall the run on banks.

He threatened to go after brokers who short-sold stock, trying to drive down prices

for later purchase. He pledged to use his own money to shore up the banking system,

urging others to follow suit. When they did so, after a nervous few weeks, confidence

slowly returned to the markets. Morgan, performing the role that the Federal Reserve

would play later, had saved the system, for now.

In the depths of the crisis, Curtis prepared to see his benefactor and present him

with a collection he hoped would rival anything Morgan dragged home from Europe. With

Myers and Phillips wandering over fresh territory in the West, the business end of

the Curtis project moved into the “publication office” of

The North American Indian

in New York. There, Curtis spent many a night in rumpled clothes, at times falling

asleep after a long tussle over his finances and the direction of his life work. He

wrote to Morgan that he’d been through quite a bit of “blood sweating” bringing the

first two volumes to the finish line, “but I’m glad to say, no delay.” He outlined

the work ahead with the Sioux and beyond, and reiterated his gratitude. The fact that

Morgan could bother with Indian pictures when the global financial system and a big

part of the Morgan empire were on the verge of ruin was not lost on Curtis. “I hesitate

in troubling you with even the briefest letter in hours like these when you seem to

have the burden of the whole land to carry. And let me say what millions know and

would like to clasp your hand and say to you: you have saved the country when no one

else could.” Whether Belle da Costa Greene passed the note on to Morgan is not clear.

He said nothing in reply.

Curtis was used to getting good press. But when two volumes printed on handmade Dutch

etching stock called Van Gelder and a thin Japanese vellum—one of 161 pages, 79 photogravure

plates and a portfolio of 39 separate plates, the other of 142 pages, 75 plates and

35 of the supplemental pictures—at last came to light in late 1907 and early 1908,

the acclaim was seismic. In appearance and texture, the books were among the most

luxurious ever printed. The images were done in sepia tones, from acid-etched copper

plates produced by John Andrew & Son in Boston and printed by Cambridge University

Press. Critics hailed a genius who made publishing history. His pictures were better

than fine oil paintings. His text would be used for hundreds of years to come—a literary,

artistic, historical masterpiece.

“Nothing just like it has ever before been attempted for any people,” said the

New York Times.

“He has made text and pictures interpret each other, and both together present a

more vivid, faithful and comprehensive view of the North American Indian as he is

to-day than has ever been made before or can possibly be made again . . . In artistic

value the photogravures are worthy of very great praise. They are beautiful reproductions

of photographs that in themselves are works of art . . . And when it all is finished

it will be a monumental work, marvelous for the unstinted care and labor and pains

that have gone into the making, remarkable for the beauty of its final embodiment,

and highly important because of its historical and ethnographic value.”

A rival paper went further. “The most gigantic undertaking since the making of the

King James edition of the Bible,” said the

New York Herald.

“The real, savage Indian is fast disappearing or becoming metamorphosed into a mere

ordinary, uninteresting imitation of the white man. It is probably safe to say that

Mr. Curtis knows more about the real Indians than any other white man.” And overseas,

where that Bible had been recast, came similar waves of praise. The first two volumes

“are among the finest specimens of the printer’s art in the world,” wrote the head

of the Guildhall Library in London, which had purchased set number 7. “One special

reason why the photographs will be more appreciated in England perhaps than America

is because

The North American Indian

is more of a novelty to us.”

Curtis was put on the same pedestal as John James Audubon and George Catlin. “We do

not recall any enterprise of a literary sort ever undertaken in America that can compare

for splendor of typography and for historical value with that which is just now undertaken

by Mr. Edward S. Curtis,” wrote the

Independent,

an American paper. “For contents, the work recalls no other similar enterprise but

Audubon’s monumental ‘Birds of America.’”

From Chicago, where Curtis had struck out with the founder of the Field Museum, more

kudos rolled his way. “It is the most wonderful publishing enterprise ever undertaken

in America,” wrote

Unity Magazine.

“If it ever comes our turn to vacate the continent, may we have as able an interpreter

and as kindly and skillful an artist to preserve us for the great future.”

In this case, superlative reviews meant nothing to the average reader, since the book

was not for sale. It could not be found in any store, and could be seen in only a

handful of libraries, by appointment. Morgan was sitting on twenty-five copies, a

plurality of the original printing, for Curtis had failed to get anywhere near the

number of subscriptions he needed. Curtis made sure that Belle da Costa Greene and

President Roosevelt saw the notices. And in his letter to Hodge about the raves, he

apologized that he wouldn’t be able to pay him, not just yet, the money he owed for

editing. Perhaps the reviews would help with a few reluctant institutions. In any

event, Curtis had had his fill of the East Coast. His mind was in Montana, and the

Battle of the Little Bighorn, there for the Indian side, yet to be told in full, a

story that might destroy the reputation of an American hero.

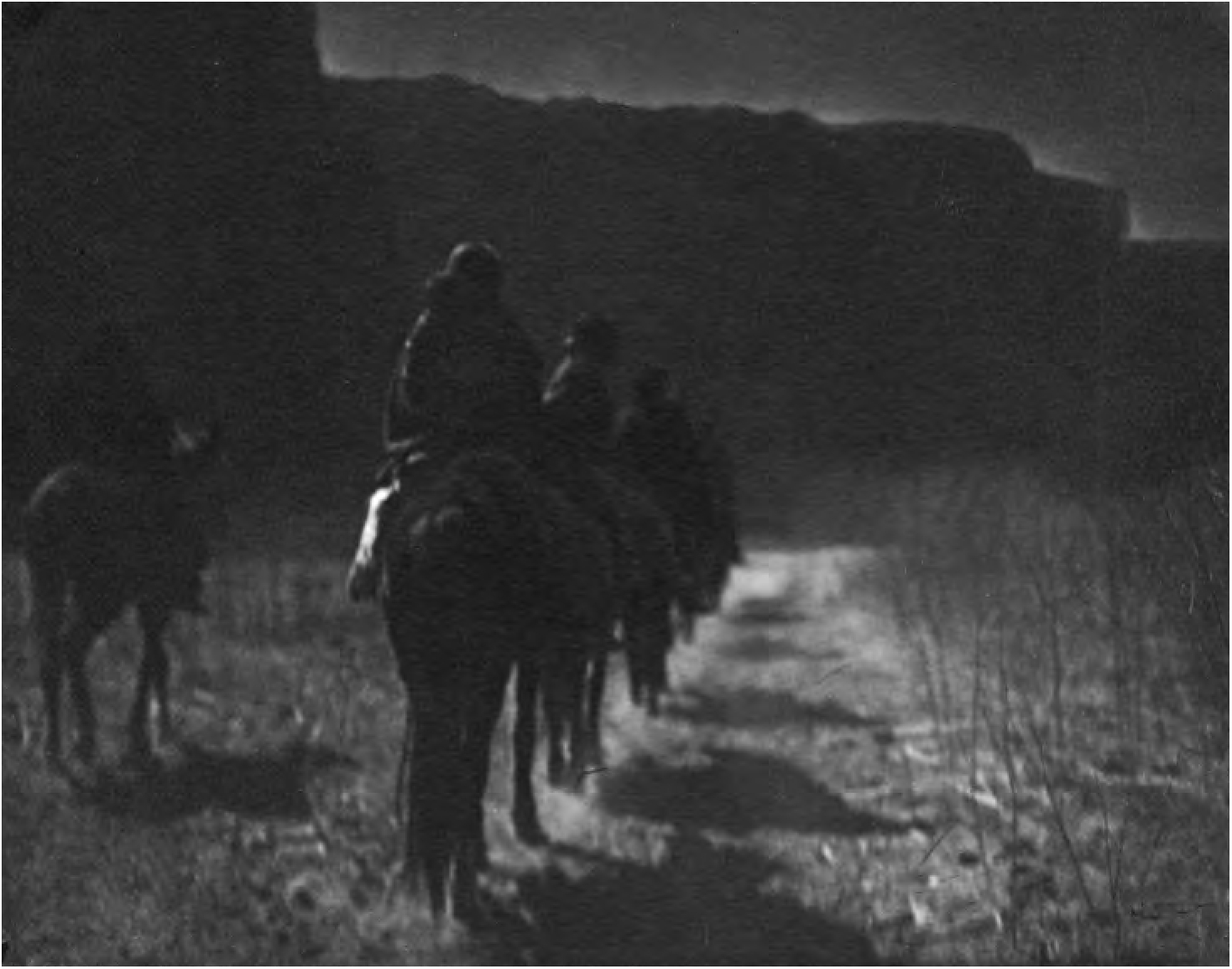

1904. Curtis chose this scene as the curtain raiser for his twenty volumes of portfolios—“a

touching, melancholy poem,” he called it. It established the theme for his work, which

the

New York Herald

called “the most gigantic undertaking since the making of the King James edition

of the Bible.”