Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher (23 page)

Read Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

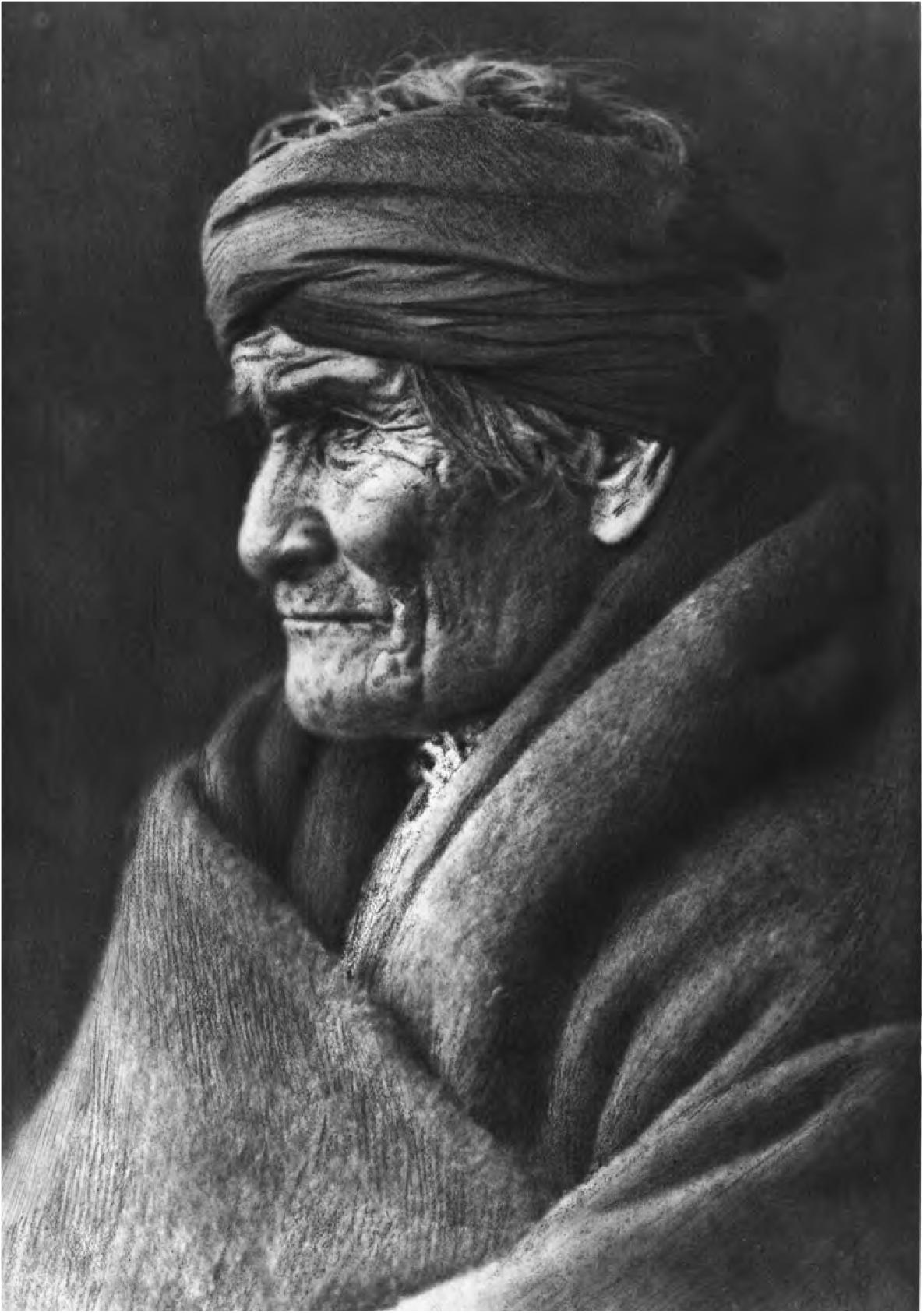

1905. A few days before Roosevelt was inaugurated, Curtis caught the hard glare of

the seventy-six-year-old leader of the Apache, who’d been invited to the White House

for the grand ceremony launching T.R.’s second term.

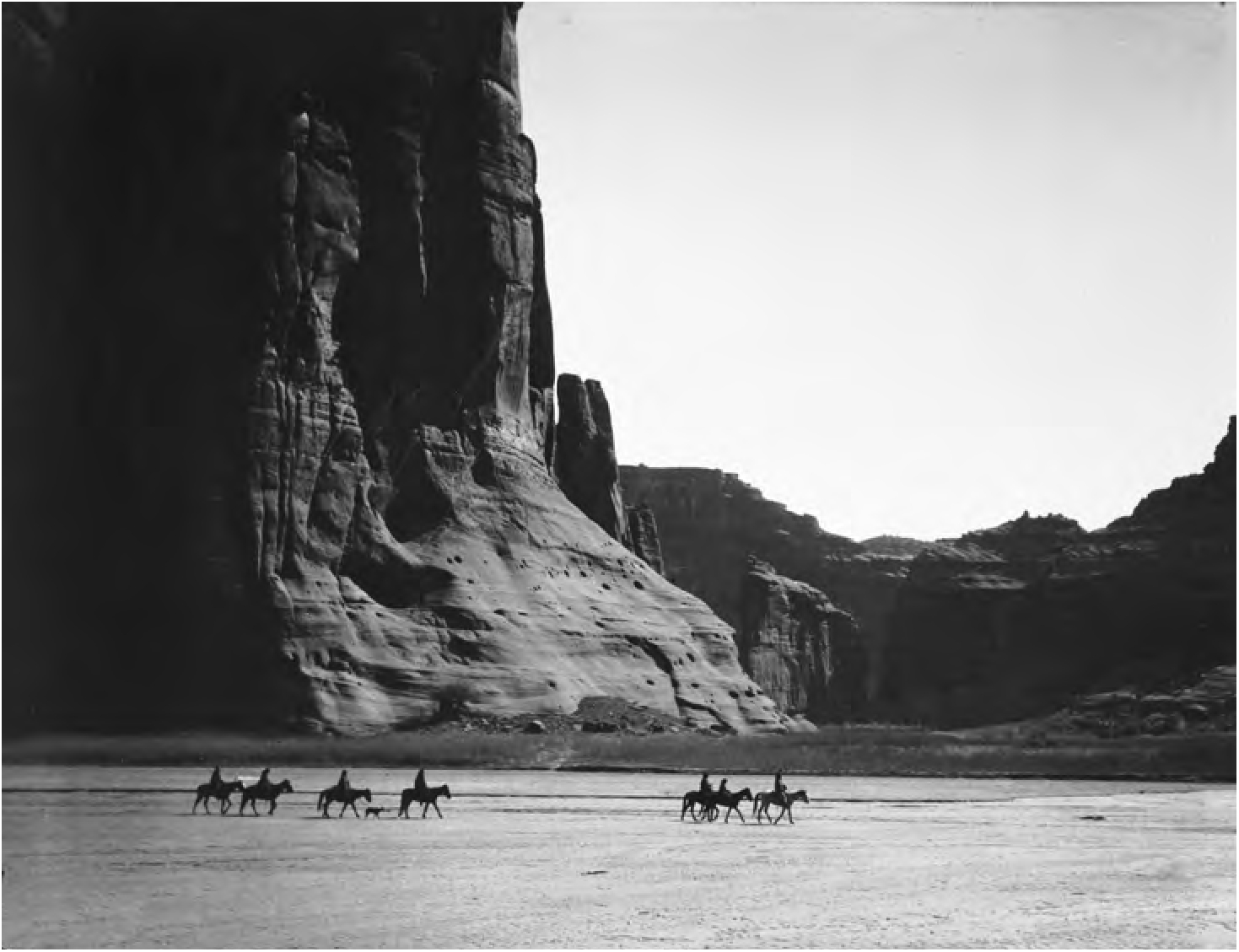

1904. In the heart of the Navajo Nation, where stone and sky dwarf humans on horseback,

the canyon is one of the most stunning places on earth.

1907–1908

H

OT SUN ON BROWN

grass in a swollen corner of Montana: Curtis walked the graveyard yet again, site

of the worst military loss by American soldiers in the West. He had been over the

killing ground dozens of times, had asked the Crow scouts who’d been with George Armstrong

Custer the same questions repeatedly, in only slightly different ways. The Indians

begged off—they were tired of talking about the Battle of the Little Bighorn, recalling

men who cried for their mothers, naked white-bellied bodies floating in the river,

puddles of blood and gnarled sinew staining the dirt. How many times did they have

to show the place—

yes, yes, this is where Custer stood!

—and swear it was the very spot where the commander of the Seventh Cavalry had taken

his last breath? How many times would they have to summon those images of slaughter

in the shadeless hills? The land drained by the Little Bighorn, with its grassy rise

to the horizon, its river-sculpted fresh bottomland, its clusters of lodgepole pine

and cottonwood, was not hard to like. In the winter, snowdrifts piled high against

granite slabs where men had fallen; in the summer, wild floral heads nodded in afternoon

breezes. But after the events of June 25, 1876, the ground could never again be just

another fold of western land that might boost a spirit at sunset. Too many ghosts

floated around, their final casting in the hereafter yet to be sorted.

An examiner of forensics and long-buried facts, Curtis was midway through a third

year of working this historical autopsy. Journeys to the Zuni and Acoma, to the Hopi

and Apache, to the Pima and Mojave—he had undertaken them over the same years. But

throughout that period, no question troubled Curtis more than this one. What really

happened on that afternoon in 1876? Some wondered why he would devote so much time

to a single battle. But the stated purpose of

The North American Indian

was to “form a comprehensive and permanent record” of the “customs and traditions”

of native people, and few traditions among the Sioux were more important than violent

conflict. And after four centuries of Indian wars—lethal clashes over ownership of

a continent—the Battle of the Little Bighorn was the beginning of the end, to be followed

a year later by the pathos of the Nez Perce’s flight and then the last roundup of

Comanche, Cheyenne and Apache stragglers.

In the summer of 1907, Curtis noticed some things and overlooked others. “The bleached

bones of troop horses and pack mules” stood out, he wrote in his notebook, and made

him wonder who rode those army animals, their ribs now whitened in the July sun. How

had they fallen?

Curtis had with him three eyewitnesses—Hairy Moccasins, Goes Ahead and White Man Runs

Him—superb sources, courtesy of the tireless work of Alexander Upshaw. All three were

Crow natives, also known as Apsaroke, of late middle age, who had been with the commander

of the Seventh Cavalry up until the final hour of his life. Custer’s company was annihilated,

of course. The Seventh lost 258 men. The three Crow guides and another Indian scout,

Curley, had fled and lived. It was White Man Runs Him who was the first to reach another

army column with the breathless report that Custer’s force had been “wiped out.”

Well into the early twentieth century, the popular story of Custer was much the same

one that went out over telegraph lines not long after his mutilated body was found.

The timing of Custer’s death—the height of America’s centennial celebration—would

not allow for nuance in the national narrative. He was the commander, all of thirty-six,

who stood his ground against impossible odds, a legend while alive, a hero in death.

This was the story boys read in school and acted out in the summer woods, one playing

Custer to the other kid’s Crazy Horse. This was the Last Stand invoked by politicians

on the Fourth of July. A biography—with Custer doomed and fearless, and Major Marcus

Reno, the commander of a routed side detachment, drunken and cowardly—matched the

press coverage. This version was popularized by the Wild West Show of the peripatetic

promoter Bill Cody. He milked it in outdoor performances around the world, complete

with an “authentic” reenactment of the battle: circus Indians whooping over mismatched

boys in blue. The last and most influential line of the legacy’s defense was Custer’s

wife, the formidable Libbie, who guarded her husband’s name like a wizened hawk sitting

on a time-frozen nest. It was Libbie who first nagged the army into moving her husband’s

body from Montana dirt to an honored grave at West Point, and she who used a web of

influential friends to silence anyone who dared depart from the story of his death.

Yes, there had been a formal military inquiry, witnesses called, field notes reviewed.

The main issue—how could a commander so misjudge the size of the enemy, thus inadvertently

leading his soldiers to slaughter—was kicked around but never resolved. Custer’s reputation

was intact.

Early evening, with the sun’s sting receding at last, Curtis moved his party uphill

to a perch of level ground that afforded a broad, sweeping view of the Little Bighorn.

He repeated every step in the staging leading up to the battle. “When the troops traveled

slow, we did the same,” Curtis wrote. “When they had halted, we halted. When the scouts

went ahead, I waited where Custer had for the return of the scouts.” Joining Curtis

and the scouts were Upshaw, translating the Indian words, and Hal Curtis, age thirteen

and endlessly entertained by the work of his father. Clara had come out to the northern

plains as well—another attempt to be a part of her husband’s life in Indian country.

She stayed back at the larger camp on the Pine Ridge reservation, the Dakota home

of the Rosebud Sioux Nation. Working with the Sioux and some Cheyenne, Curtis had

conducted several rounds of interviews with veterans who took part in the fight. From

them, he heard that Custer’s eardrums were pierced by women before the blood on his

face had dried, because he refused to listen. He was told of the bravery of Crazy

Horse, who’d been swimming when the battle started, then had quickly mounted a horse

and made several daring charges to split Custer’s men. “Let us kill them all off today,”

he said, “that they may not trouble us anymore.” And this rare victory was given the

usual cast by the Americans: when Indians won, it was always a massacre.

Curtis had also walked the battlefield with these Indian victors, these still proud

Sioux of the western subtribe who called themselves Lakota. He sat where bodies were

found, pressing for information about strategy and intent. He recorded many anecdotes,

the violent vignettes somewhat altered by time, but he wanted the bigger picture.

“They could tell vividly of their actions,” Curtis wrote, “but could give no comprehensive

account of the actions as a whole.” Already he had taken many pictures of the participants.

He was fond of Red Hawk’s portrait, his eyes full of tragedy, half his face obscured

by a droopy war bonnet, and wrote that his “recollection of the fight seemed particularly

clear.” Red Hawk appeared to be fond of Curtis too, giving him the Sioux name of Pretty

Butte. It was Red Hawk who posed for Curtis atop a white horse drinking water at a

stop, the picture titled

An Oasis in the Badlands.

There, the ninety-one-year-old Red Hawk is shown on his mount with a rifle protruding

from a simple saddle—a pose meant to convey that the Sioux still had some fight left

in them. What Curtis saw in the Sioux was what rival tribes feared in them: a fine-honed

tradition of war makers and buffalo chasers, scary good at bloodletting.

Now Curtis concentrated his work on the other side of the battle, those Indians who

had worked for Custer, longtime enemies of the Sioux. The Crow feared the Sioux more

than they did the whites. If captured by a Lakota, a Crow knew he would be facing

mutilation, burning, eye-gouging and other forms of slow torture. So when Custer and

his bluecoats arrived with cannons and rapid-firing guns, the Crow saw a chance for

a permanent advantage in the northern plains. If the army could do something about

another Crow enemy, the Cheyenne, it would further serve their purposes. The Crow

scout White Man Runs Him had led the Curtis party up the Rosebud River, one rise over

from the Little Bighorn, following the path where Custer broke from his main command

on the Yellowstone. The party walked the easy miles to the divide, one side falling

away to the river they had just followed, the other giving way to the bumpy valley

of the battle. They dropped down a bit, to a lookout known as the Crow’s Nest. It

was here, said the scouts who had led Custer, that they first saw the Indians camped

below. Most of them were Sioux under the guidance of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse,

though they had with them a sizable contingent of Cheyenne and Arapaho.

The Cheyenne had good reason to hate the Americans. Over three hundred years of contact

with whites, from their migration out of the upper Mississippi headwaters, to the

northern plains, to the eastern Rocky Mountains, the tribe had warred, traded and

hunted their way to upward mobility. But then came the Sand Creek Massacre, on November

29, 1864, the most brutal slaughter of Indian innocents by U.S. combatants. A camp

of about five hundred Cheyenne, almost all women, children and old people, had made

a peace pact and were gathered under an American flag in Colorado when they were attacked

by a former Methodist minister, J. M. Chivington, leading a volunteer army of drunks

and malcontents. Curtis described what happened in Volume VI:

“. . . practically all were scalped, and that women as well as men were so mutilated

as to render description unprintable; that in at least one instance a woman was ripped

open and her unborn child thrown by her side; that defenseless women, exposing their

breasts to show their sex, and begging for mercy, were shot down with revolvers placed

practically against their flesh; that hours after the attack, when there was not a

militant Indian within miles of the camp, children were used as targets.”

The Indian scalps were later displayed, to great whistling and applause, at an opera

house in Denver. Four years later, Custer wiped out a village of Cheyenne on the Washita

River. Approaching the Indians in that encounter, one of Custer’s officers wondered

what they would do if they found themselves outnumbered. “All I am afraid of is we

won’t find half enough,” said Custer.

There were certainly more than enough Cheyenne and Sioux camped along the Little

Bighorn. Women and children, thousands of ponies and hundreds of tipis made the gathering

appear a vast, almost festive tent city of smoke, dust and chatter. About 5,000 Indians

were in the valley, though the numbers varied in all accounts, and the scouts could

not judge the size by what they had seen. Custer’s men numbered 650 soldiers.

A bit closer to the Little Bighorn, Custer broke up his forces into three battalions.

The prize was in his grasp; he was not about to let the enemy slip away and bring

glory to some other commander in what might be the last battle of the Indian campaigns.

One flank, under Major Reno, veered left and south, downward to the river, to cut

off any escape. Another remained on higher ground. Custer moved in the general direction

of the camp, though he stayed above the river, roughly parallel to it. In early afternoon,

Reno ordered his men to battle. They charged into a thicket of small trees and brush,

confronting women and children who appeared in a panic. The gunfire roused the warriors,

who quickly massed. They swarmed Reno’s men and set fire to the brush, pushing them

into defensive positions in the timber. Reno was a brooding man, prone to drink during

the day until he passed out at night. He and Custer, a teetotaler, despised each other.

As it became apparent to Reno that his men would be routed, he ordered a retreat.

His words are not carved in stone at West Point: “All those who wish to make their

escape follow me!” It turned into a run-for-your-lives, desperation scramble, but

it ultimately saved Reno and many of his men.