Sleight (8 page)

Authors: Kirsten Kaschock

LARK’S BOOK.

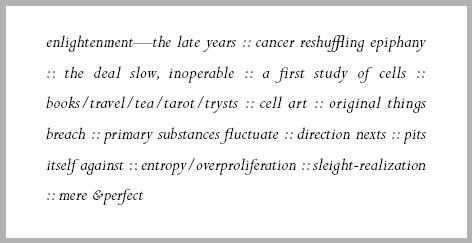

[On the first four pages, detailed pencil-drawn diagrams.]

Sketch one: Suggestive of a spiderweb with a central snarl. Cause unclear. Or a game of cat’s cradle with the children’s fingers removed.

Sketch two: A family of trapezes. Horizontal bars with connective tissue everywhere indicating attempted and aborted support.

Sketch three: Parabolic. Small line fragments arranged to describe waveforms. A digital tide that could be construed as the splintering of a single gull.

Sketch four: A machine with pulleys. All lines reach to a central form. The proposed function either to raise up or to strangle.

[On page five, a newspaper clipping. A photograph with no caption. In the photo a bound man is being dragged behind a military jeep by his legs. His face is to the pavement. It is impossible to discern whether he is still alive.]

[On page six, Lark’s handwriting begins.]

I’m back here. Have decided to stay. I have nowhere else. The ghosts aren’t as thick as I expected. I came two weeks ago to clear out, maybe sell some things. I found my old papers. I recopied four drafts I did of the first Need. I got better at putting them down, I think. Still, these first attempts aren’t bad. I was only thirteen. I can’t believe Jillian never found these. Not that she cleaned. She never mentioned them. They were under the windowseat, just where I put them. It’s helpful here. The dogwoods. I’m going to make soup tonight that should last the week. I went to the farmer’s market yesterday and saw people. That girl from French class with the hips. The black boy I had a crush on junior year. He remembered me. I couldn’t think of his name. I was rude, asked, my North coming out. Drew. We talked a little. He had the paper in his hand. This picture was on the front page—I kept looking down at it. I couldn’t keep up my end of the talking. Drew noticed, gave me the paper, said he’d see me around. It’s possible now, I suppose, that I could have that sort of life. Except—the man’s face. I keep seeing how it must’ve left a trail of blood and saliva, skin and bits of bone on the asphalt—a screaming of. Itself. Into the asphalt. And so, now, I can’t help thinking—what sort of life happens prior to that? What sort of life is possible with that death waiting?

West shut the book. He spoke to Clef.

“Do you mind if I take this with me?”

“I said you could.”

“Your sister, where is she now?”

“In Georgia, where we grew up. With her husband and her little girl.”

“Would you mind if I called on her?”

“Called

on her?”

“I would like your permission, of course, but I’ll do what I have to.”

Kitchen knew what West had seen, but asked him anyway. “What did you see?”

West looked at Kitchen warily, but with eyes too tired to lie. “I saw a horse, legs buckling under, coming down. I saw white boots caked in red mud. And a child old enough, for once, to run.”

CELL.

F

ern lived in a twenties-era apartment on the Upper East Side. The apartment was white. Everything in the apartment was white except for the wooden floors. But every white thing was a different shade of white, and every hard white thing was draped in volumes of white fabric. West had always thought of his grandmother’s place as exclusively hers, not his at all, but warm. Warm and clean—a guest towel folded on top of the bathroom radiator.

His grandmother, perfectly rendered though wasting, was curled up on the couch in an ivory afghan, drinking tea. Her face was gaunt and glowy. She continued, even in stage four, to look twenty years her junior.

Good rouge,

West thought.

“How are you feeling, Fern?”

“Come off it, West. Why don’t you just tell me why you’re here?”

West went from shamed to defiant in three seconds, and so subtly Fern barely caught it, and she was the only one who could have.

“It’s always money, isn’t it, Fern?”

“It always is.”

“Well, I need two extra salaries, and the sponsor won’t budge.”

“The sponsor.”

“Yes, the sponsor, Fern. We could’ve been the only troupe in the world privately funded, unsullied by the Vice Corps,

14

but you had other plans for your wealth.”

“I did.”

“And how’s that going for you? Your charity?”

Fern decided to ignore West’s sneer. She looked directly at him, and answered the question as if it were honest. “I think we’re doing well. I haven’t been down to see the girls since the cancer took this turn. But I get letters.”

“They write?”

“There’s a school at the compound. Most of them are still school-aged when we get them off the street, West. They get used up pretty quickly.”

West was done with the conversation. “So, can I have it or not?”

“When have I ever denied you?”

“You denied me the time I refused to ask.”

“There you go.”

As West walked toward the park, he relaxed. He’d gotten the money. He would send Byrne down to meet Lark. He had a feeling they would work. What he needed now was to sit and think about next. Something bigger?—always a temptation. Maybe technology.

He was at Alice. He always ended up at Alice. Her, big and bronze on her big bronze mushroom, arms outstretched. Him—having run away from Fern at nine, ten, twelve, because she’d been making him listen about his father, or about practicing, or because there was another one of her women in the apartment. The summers in Boston while Fern taught at the academy had been worse. She’d tried to make him rehearse with the other students there—the best from small towns all over the country. Most of them female. And when he’d gotten frustrated by his inadequacies, when he’d thrown down his architectures or tripped over someone else’s—there was no Alice to run to. No big bronze girl blithely holding court among others’ absurd expectations.

West watched as a little boy climbed onto her lap with the help of his father. West’s father still lived and worked downtown, he assumed. It had been over a decade. The few times his father had been to see West, the three of them—Fern, West, West’s father—had gone to eat at a place with dark green walls where waiters refolded his napkin every time he went to the bathroom. He’d always gone to the bathroom at least once during those dinners. Because the soap there smelled like other countries.

Fern had made West keep a daily journal since he’d turned ten. In it, there was a page-long entry about soap. Soap that didn’t smell like his grandmother. She told him each night what to write in his journal, and that night he disobeyed. When they came back from the restaurant and his father took off—again—Fern said West should write about how he felt, and he wrote about soap. Musky soap. Soap that didn’t smell like clean. Stolen soap he’d hidden under his bed in a small leather suitcase with buckles.

In his late teens, West discovered that the journal was a sleight tradition. He read around in several of the diaries kept in the academy book room. Sleight’s founder had made her protégées take notes on every performance: imperfections, serendipities, suggestions.

15

Before they attempted their first tour, Antonia had her sleightists research the towns through which they would caravan, including chief industries, average per capita income, ethnic makeup, and weather. The performers became fixtures at the newly opened Free Library of Philadelphia. Their journals were dry, full of statistics and numbers—and for the most part, absent the authors themselves.

West supposed he was fortunate. His grandmother had only had him take notes on people: what they said, how they said it, how they moved, what they looked like, what they wore, what they didn’t say. No research required, only a sound eye. When, as an adolescent, he’d toured East Asia as a roadie/techie/usher with Kepler, she’d quizzed him nightly on the composition of the audience and the demeanor of the critics. West, lacking the finer motor skills, lacking hand-eye coordination, gained a knowledge of humanity both indispensable and dreadful. And unlike Antonia’s disciples, he was always present in his journal entries—as adjudicator. Fern did that for him.

West looked down at the dedication plaque embedded in the concrete below Alice. George Delacorte had commissioned this statue in memory of his first wife, Margarita, who had loved children. But Fern, facing her own death, hadn’t bought art. Instead, his grandmother had abandoned her measuring stick to fix a bunch of broken Mexican dolls. The Queen adrift in the repugnance of the world—caring. The Queen drowning in decapitation, all the while ordering the pretty heads back on. Screwing them on with hands that had smelled always of lavender. At the end of a long selfish life, false selfless acts. Queen Hypocrita. Queen Early, too late, too late. West checked his empty wrist, headed over to Fifth Avenue, caught a cab to La Guardia.

West was trying to decide whether or not to go down to Georgia. As facilitator. He didn’t know what to expect from this Lark. Her book was a singularity, an event. There was no doubt the things she drew—what she referred to as Needs—were some of the most complex, breathtaking structures West had ever come across.

T said she thought Byrne’d be back in York that day or the next. West had long before learned to trust T’s clock, set to otherworldly yet intensely corporeal rhythms, so he booked two train tickets south for the weekend. Some time alone with Byrne might give him a chance to explain Lark’s book, at least what he’d made of it. And to repair some small rifts. West wasn’t unaware of Byrne’s disillusion with tour—he would’ve had to have been blind, or extremely opaque. He was neither. West was rushing this meeting precisely because Byrne seemed so precarious, unable to juggle his talent in its new setting.

Crater. Roof. Abomination. Rock. Starless. Shorn. Devotion-blanket. Parallel. Ash.

Byrne’s precursor for

Poland

had mesmerized. West would not let him drift off—not with things at stake.

West felt his heart gallop. He read its stop and surge not as his own demise but rather as a metaphor for the apocalypse. Bodies, he knew, housed the ends of their lives. Also beginnings.

14

Vice Corps: the nickname given by sleightists to the group of industries that have traditionally sponsored their art. Liquor companies, Big Tobacco, porn, the pharmaceuticals. They advertise in sleight’s playbills and use the goodwill they gain by erecting theaters (primarily in suburban communities) to garner tax breaks on other real estate ventures in those townships. Sleightists, as a matter of course, despise their sponsors. Sleightists also tend to drink, smoke, and have sex more often than many of their suburban neighbors—or used to, according to a Kinseyan endnote. These days sleightists are perhaps most anomalous in that they remain troubled, if abstractly so, about the ethical ramifications of patronage.

15

Her father wrote of her: “Antonia is brilliant like a polished egg.” He had had her educated in Florence and then Paris while his aristocratic status allowed him to spend his own time on pursuits—chemistry, mathematics, comparative anatomy. A great many days of Antonia’s vacations were given over to his dictation before she was disowned for her involvement with dance (“I indulged her interests, yes, but she was never to debase herself on an actual stage.”). Antonia performed throughout Europe and Russia, and finally in America. It has been suggested that she came upon the documents in Prague and followed them, seducing Dodd in order to have him procure them. What is known is that she is the mother of sleight. Beyond that, Antonia remains an enigma who demanded a previously unseen caliber of physical dexterity and decorum from her charges—mostly young women plucked from callings grittier than the theater, and a few boys of like circumstance.