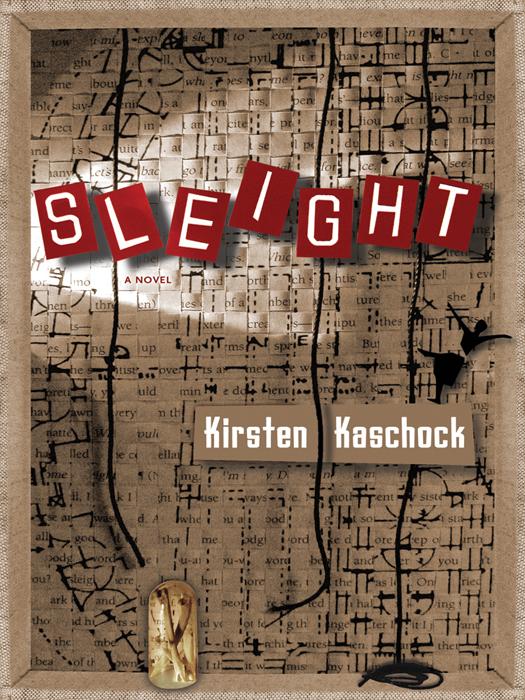

Sleight

Authors: Kirsten Kaschock

SLEIGHT

A NOVEL

Kirsten Kaschock

COFFEE HOUSE PRESS

MINNEAPOLIS 2011

COPYRIGHT © 2011 by Kirsten Kaschock

COVER AND BOOK DESIGN by Linda Koutsky

AUTHOR PHOTO © Daniel R. Marenda

Coffee House Press books are available to the trade through our primary distributor, Consortium Book Sales & Distribution, www.cbsd.com or (800) 283-3572. For personal orders, catalogs, or other information, write to: [email protected].

Coffee House Press is a nonprofit literary publishing house. Support from private foundations, corporate giving programs, government programs, and generous individuals helps make the publication of our books possible. We gratefully acknowledge their support in detail in the back of this book.

To you and our many readers around the world,

we send our thanks for your continuing support.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CIP INFORMATION

Kaschock, Kirsten.

Sleight : a novel / Kirsten Kaschock.

p. cm.

Summary: “Sisters Lark and Clef have spent their lives honing their bodies for sleight, an interdisciplinary art form that combines elements of dance, architecture, acrobatics, and spoken word. After being estranged for several years, the sisters are reunited by a deceptive and ambitious sleight troupe director named West who needs the sisters’ opposing approaches to the form-Lark is tormented and fragile, but a prodigy; Clef is driven to excel, but lacks the spark of artistic genius. But when a disturbing mass murder makes national headlines, West seizes on the event as inspiration for his new performance, one that threatens to destroy the very artists performing it. In language that is at once unsettling and hypnotic,

Sleight

explores ideas of performance, gender, and family to ask the question: what is the role of art in the face of unthinkable tragedy?”—PROVIDED BY PUBLISHER.

ISBN 978-1-56689-275-9 (pbk.)

1. Sisters—Fiction. 2. Dance companies—Fiction. 3. Domestic fiction.

I. Title.

PS3611.A785S57 2011

813’.6—DC22

2011024142

ISBN 978-1-56689-293-3 (ebook)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

An excerpt from

Sleight

appeared in

Action Yes Online Quarterly

and in

Xantippe.

Profound gratitude to my siblings: Alex, Mary, Taryn, and Misha. Deepest thanks also to Ann and Alex Kaschock, Reginald McKnight, Jed Rasula, Judith Cofer, Sîan Griffiths, John Woods, Sabrina Orah Mark, Kristen Iskandrian, Mark Leidner, Heather Cousins, Alan Sener, Françoise Martinet, Sarah Jane Duax, Patrick Lawler, George Saunders, Mary Karr, Richard Cook, Ron and Mary Williams, Derek Ege, Ali Delgadillo, Marquet Lee, Maureen Smith, Mikey Rioux, Katie Zeller, Linda Koutsky, Sarah Yake, Anitra Budd, and all of Coffee House Press. Unabandonable love to my children—Simon, Bishop, and Koen.

This is a work of fiction: any Needs in this book that resemble Needs of the world

do so inadvertently and probably unavoidably.

To Danny (who pins me to this place)…

I have decided—I will let you.

Now, do you doubt that your Bird was true?

—EMILY DICKINSON

D.C. INSIDELOOP

JAN. 13, 2001, PP. 52–6

Interview with Clef Scrye, member of the sleight troupe Monk

INSIDELOOP: Clef—I don’t think I’ve heard that name before. Not for a woman.

SCRYE: I’m sorry, was that a question?

INSIDELOOP: No … I’m sorry. Would you mind if—may I begin again?

SCRYE: You can try.

INSIDELOOP: Please, Ms. Scrye, I wonder how you might explain a sleight to someone who has never seen one?

SCRYE: I couldn’t. No, I mean that. Sleight isn’t … well, it’s beyond anything it may have come from. Or out of. There’s no disagreement about that.

INSIDELOOP: And what does it come from? What, exactly, is sleight made of?

SCRYE: It’s impossible to say—“openings” is a term one hears, “suspensions,” but that implies a bridge between things, and that’s not quite … at any rate, at several points during a sleight performance—you’ve got epiphany.

INSIDELOOP: Let’s step back. I go to my first sleight performance. What will I see?

SCRYE: Oh. You want me to lay it out. Okay, but it won’t help. In most sleights, except West’s of course, first a sleightist arrives in front and recites the precursor. Tedious, but if you miss it, the rest seems less—what? linguistic maybe? unlocked? Then, the curtains—just like at the opera or ballet or theater. It has nothing to do with the elements per se. Then, the lights fade up, illuminating the sleightists already onstage with their architectures.

INSIDELOOP: Which are?

SCRYE: Yes. Sorry. Transparent and flexible frameworks—moveable polyhedrons and so forth. Each sleightist (there are twelve in every troupe, nine women and three men) carries one of several architectures he or she has trained with. Sleightists manipulate these frameworks in and around our bodies, linking them up to create forms that span the stage. But you don’t … I mean the audience can’t … the sleightists’ movements are timed, the works navigated in such a way …

INSIDELOOP: Yes?

SCRYE: Well, theoretically, you could examine the documents beforehand, know exactly the structures the hands have drawn—every form the sleightists will be moving through in a given evening … but it wouldn’t matter.

INSIDELOOP: What wouldn’t?

SCRYE: What you know about a sleight. It doesn’t matter. What you’ll see is … well, West calls it “the constellating empty.” But West … I think West—West can be bleak.

INSIDELOOP: How did you become a sleightist?

SCRYE: [ …]

INSIDELOOP: I’m sorry. Do you need a moment?

SCRYE: No … thank you. I think … well, I think I sleight because I always have. My mother sent my sister Lark and me, I guess for poise, and I was good. And when you are good and a girl at something, you stay with it—maybe for all the goodgirl words that come. Goodgirl words like do more, keep on, further—instead of the other goodgirl words—the if-you-are-you-will words—be nice and softer and you-don’t-like-fire-do-you? In sleight there was less of that so more of me, until there was less. Once I tried to leave it, right after Lark did, and felt like half. Most people are satisfied with half, not knowing what it is to hold a thousand hungers suspended and you not feeling the hunger. After I quit I just wanted, all the time, to be in the chamber. To be stranded with my architectures—then, to abandon them, moving. To watch beauty, of its own accord. Yes. I think I missed my missingness.

A SOUTHERN.

You are living on the site of an atrocity

L

ark stopped at the light. Her right hand, a severe blue, knuckled the wheel. Her eyes narrowed. Her left hand, also blue, impatiently pushed a nothing back into place behind her ear as if it were a loose, transparent curl—her actual hair cropped almost to the scalp, a silvering black. The billboard had been up for two weeks or more. That Wednesday it looked at her hard.

Lark hadn’t been a sleightist for long, but she hung on to it. Few lead more than one life before thirty. Those few, Lark noted, tended not to bond. Lark’s husband had always been who he was. He’d changed, but not into someone else. A harder else. Lark would come home and Drew would be reading to Nene or cooking dinner and he would look up and it would be him. Lark found that remarkable.

That Wednesday Lark came in and spoke billboard to Drew. She said, “We are living on the site of an atrocity.” Drew looked at Lark, smiled as if from under a river, and said, “No, Lark—we’re not.”

Lark sold Souls at a kiosk in University Square. She did okay. Made enough for Drew to stay home reading, writing, minding their girl. He taught an occasional course at the community college, to keep himself whet. Lark did brisk business when it was warm. When it was cold, people made do with what they had. But Georgia winters weren’t long, and she had a space heater. Januaries, she kept shorter hours, and when it got glacial—for Georgia, anything below freezing—she meditated on Paul Revere.

Her first summer at the academy, Lark had visited Revere’s church in north Boston. A favorite instructor, Ms. Early, had suggested the trip: the interior of the church, she’d said, was a remarkable example. All the pews boxed, every family segregated from every other, and the minister pulpited up high, on an octagonal dais far higher and smaller than a stage. An eternal white stop sign. Lark thought these revolution-era Bostonians must’ve been cold—to wall off from neighbors even in church. It was some other tourist who asked the question, “Why are the pews boxed out like that?” The caretaker or security guard or unpaid, leisure-class but socially responsible intern explained that the church hadn’t been heated in the 1700s; instead, families had stowed hot bricks under the pews. Short walls kept in heat, out drafts. Lark felt mean. A week passed and she forgave herself, figuring she’d still been right about the cold. Three Boston summers later, she decided centuries of heated churches had done and would do nothing for the city. The interior structure of the church, however, stayed with her. If she had been a hand

1

Lark might have used it to draw.

Lark wasn’t a hand—she sold Souls. She was proud of her Souls. They were pricey, but she wouldn’t bilk or bicker. Her Souls were pocket-sized, responded to the warmth of the palm, had a good weight to them. Lark got a lot of browsers. A student might look at, fondle, then reluctantly set a Soul back onto its cloth, sometimes twice a week over three or four semesters before committing. Lark’s daughter Nene adored the four she had, one for each birthday. She’d recently given them names: Fern, Marvel, Newt, and the Lacemaker.

On the Monday after the billboard, a man came up to the kiosk and asked for two Souls—one for himself and one for the road. His dashboard? Lark was curious.

“What kind of car do you drive?” He didn’t look like he drove a car.

“Not for a car—for the road. I’m gonna bury it under Space Highway.”

Lark thought she was prying but went in anyway. “Can I ask why?”

“Because of the atrocity,” he said.

1

In sleight, a hand is recognized and promoted by a number of instructors. The child is studying sleight, has a deep love for it, but cannot manipulate the architectures. Some hands exhibit defects that make the most significant figurations difficult for them, if not impossible. Other hands simply seem to lack physical ability or to have problems with pain. Because of the intensity of the intervention by the instructors, certain members of the sleight community wonder if potential hands have been overlooked—nonfacilitated—because of their competence.