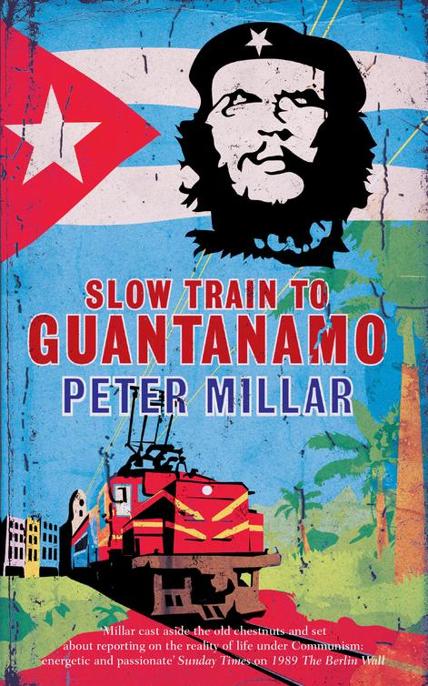

Slow Train to Guantanamo

Read Slow Train to Guantanamo Online

Authors: Peter Millar

Praise for Peter Millar

Slow Train to Guantanamo

‘The book gives an insight into Cuban daily life, Caribbean communism, the food, the beer, the colours, the smells (good and bad) and the realities of an artificial economy that the package deal tourists will never even glimpse. If you have ever been to Varadero and Havana (the standard package), read this book, then go back and see the real Cuba whilst you still can. If you have never been to Cuba, read this book, and if you then don’t want to go to Cuba, you have no soul, and they wouldn’t want you there anyway. Go to Cuba, but take your own toilet seat, and paper, the locals will understand’ – J. P. Hayward

1989 The Berlin Wall

‘The best read is the irreverent and engaging account by Peter Millar, who writes for the

Sunday Times

among other papers. Fastidious readers who expect reporters to be a mere lens on events will be shocked at the amount of personal detail, including the sexual antics and drinking habits of his colleagues in what now seems a Juvenalian age of dissolute British journalism. He mentions his long-suffering wife and children rather too often, but the result is full of insights and on occasion delightfully funny. The author has a knack for befriending interesting people and tracking down important ones. He weaves their words with his clear-eyed reporting of events into a compelling narrative about the end of the cruel but bungling East German regime’ –

Economist

‘The most entertaining read is Peter Millar’s

1989

The Berlin Wall: My Part in its Downfall

, a witty, wry, elegiac account of his time as a Reuters and Sunday Times correspondent in Berlin throughout most of the 1980s’ – Spectator

‘

1989 The Berlin Wall

is part autobiography, part history primer and part Fleet Street gossip column … Millar cast aside the old chestnuts and set about reporting on the reality of life under communism. In bare Stalinist apartments, at hollow party events and over cool glasses of Volker the gravedigger-cum-hippie, the Stasi seductress “Helga the Honeypot”, Kurtl the accordion player whose father had been killed at Stalingrad, and the petty smuggler Manne who has been separated from his parents by the Wall … Energetic and passionate …’ –

Sunday Times

All Gone To Look for America

‘Succeeds in capturing the wonder of America that the iron horse made accessible to the world’ –

The Times

‘Witty yet observant … this book smells of train travel and will appeal to wanderlusts as well as armchair train buffs’ –

Time Out

‘Fills a hole for those who love trains, microbrewery beer and the promise of big skies and wide-open spaces’ –

Daily Telegraph

The Black Madonna

‘With a journalist’s keen eye and ear, and a born storyteller’s soul, author Millar has written a truly compelling, globetrotting thriller. Rich in history and cultural detail,

The Black Madonna

is a page-turner of a novel that flings us into the heart of the essential conflicts of our times. Look out, Dan Brown, make way for Millar’ – Jeffery Deaver

Stealing Thunder

‘An intelligent thriller … fast-paced and convincing’ – Robert Harris

PETER MILLAR

SLOW TRAIN TO

GUANTÁNAMO

A Rail Odyssey through Cuba in the Last Days of the Castros

Contents

The City (not quite) by the Bay

Da Coda: Santiago and the ‘French Train’

It is nearly twenty-five years since all of a sudden communism keeled over and died. The

annus mirabilis

of 1989, when the Cold War caught its death, the Berlin Wall crumbled, the dominoes of the Soviet empire in Eastern Europe tumbled and in quick succession the Soviet Union itself disintegrated, seems a lifetime ago. So long, in fact, that it is hard to remember that back then it was widely considered that capitalism had won and was from now on invincible as a global economic and social system.

Five years after the great financial crash of 2008, that no longer seems such a wise conclusion.

Apart from the aberration of China’s adoption of a strange form of capitalist communism, only two states remained that genuinely considered themselves dedicated to the principles of Marx and Engels: North Korea and Cuba. Both were considered, particularly by the United States, little better than pariahs, with sanctions imposed against them.

The reality, of course, was always dramatically different. While North Korea was, by and large, a cold and barren half-peninsula, Cuba is one of the most beautiful, sun-blessed islands in the Caribbean. While the North Korean people were drummed into regimental parades and marched through the streets of Pyongyang, the Cuban people drummed, played and sang themselves into and out

of the bars of Havana and onto the big screen. While North Korea’s leaders died and succeeded one another in dynastic fashion, Fidel Castro hung on, seemingly forever, until eventually, in 2008, in admittedly similar dynastic fashion he yielded power to his not much younger brother Raúl.

And now Cuba is changing. Raúl himself has said he will serve five more years at most. Cuba beyond the Castros is already on the horizon. What will it be like, and more to the point what is it like now, outside the luxury enclaves visited by most beach-loving foreign tourists, in the streets, buses and trains used by the ordinary people?

As someone who lived in East Germany, the Soviet Union and communist Poland and reported on life in those countries before the fall of the Iron Curtain

1

and immediately afterwards, Cuba exerted a remarkable fascination. And as someone who has travelled the length and breadth of the United States by the method of transport that created that continental nation,

2

it seemed to me there could be no better way to experience life in Cuba on the ground, literally, than by travelling the length of the island by train.

Cuba’s railway is – or was, as I was about to find out – one of the first and most extensive national systems in the world. Cubans had the fifth national railway system in the world, after the United Kingdom, United States, Germany and France, before Spain or most other European countries, and it remains the only truly national system in Latin America. Although just how extensive it was I had no idea.

This is not a guidebook, not a book about politics, nor even, I regret to tell railway buffs, a book about trains. It is a book that deals with all those topics and I hope a lot more. It is a book about people and places and country on the cusp of change. It is a book about travel and why it is the best

education the world can offer. It is about life and living it, the Cuban way. And believe me, for all the deprivations the Cubans today still suffer, there are worse ways to live. Far worse. Ask anybody in Iraq or Afghanistan.

1

.

1989: the Berlin Wall (My part in its Downfall),

Arcadia Books 2009.

2

.

All Gone to Look for America,

Arcadia Books 2008.

It is 4.10 a.m. on a dark, steamy tropical morning and raindrops that look and feel like drowned bluebottles are falling from the rusting corrugated iron of the station roof. I have just been poured out of a train the Cubans nickname

El Spirituario

– an experience as close to being below decks on a seventeenth-century slave trader as a middle-aged, middle-class European man ever wants to get.

I stumble down the station steps in search of transport to where I am hoping to find a bed for what remains of the night. The options are not great: a donkey-cart with a candle burning in a jam jar as its tail light, or an ancient Soviet Lada with only one door, no windows and a patchwork quilt of badly-stitched upholstery.

This is Santa Clara, capital of the cult of Cuba’s secular saint and martyr, the chess-playing, motorcycle-mad humanitarian medic and ruthless revolutionary who looked like a movie-star; his iconic image has stared from bedroom walls of generations of liberal students across the globe for more than half a century. It was here that Argentinian Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara won the battle – in reality little more than a train derailment and subsequent skirmish – that would give control of the Caribbean’s capitalist playground to the Communist Fidel Castro. The aftermath of the Battle

of Santa Clara would make Che a household name in almost every nation on the planet.

And I hate to say it, Che, I really do, mentally addressing myself to the ghost that hovers over Santa Clara, but it looks like a crock of shit.

After four hours on an overcrowded train in 30ºC heat and 80 per cent humidity, with broken seats, no windows (thankfully), compartments with no doors and endlessly flickering fluorescent corridor lights, all I want to do is sleep. I decide to leave the candle-burning donkey-cart for another time and opt for the less rustic but possibly faster option, the one-doored Lada.

I had thought that maybe one reason communism still survived in Cuba might be the weather: it’s a lot easier being poor when the sun is shining, but now I’m not so sure.

Ten minutes after falling into the Lada, the rain is still beating a slow staccato on the roof and my sleep-starved brain has been addled by a ghetto blaster strapped to the passenger seat sun visor blaring at full blast as we rattle along otherwise empty and silent pre-dawn cobbled streets.

My driver is wearing rain- or sweat-soaked red shorts and torn orange T-shirt. He grins, gleefully unembarrassed by the high-volume salsa and farting Soviet exhaust pipe, as we scan the shuttered front doors behind ornate iron grilles in a street of low terraced whitewashed eighteenth-century Spanish colonial houses. One of these is the

casa particular

– a private home licensed to take in foreign guests, the Cuban equivalent of a B&B – where I have booked a room. But which one? The concept of giving houses numbers or even names, if ever common, has clearly fallen into disuse. But then as buying or selling homes has been banned for half a century, pretty much everybody knows who lives where.

I stare in bleary despair at the lack of identification when an elderly white-haired gentleman, roused to our presence

by the cacophony on his doorstep, opens shuttered doors, then the elegant wrought iron-grille in front of it, and beckons me in.

The Lada driver pockets his fare and his ramshackle vehicle with under-inflated tyres, elaborate upholstery, and missing door rattles off into the predawn twilight, the tinny din from its improvised audio equipment mercifully vanishing with it as my host welcomes me into another world. Or perhaps as L. P. Hartley would have put it, another country: the past.

Beneath my feet is an ancient hardwood parquet floor, ahead of me two white Doric pillars flank the entrance to an open courtyard, like the interior of a Moroccan

riad

, with tall double doors ahead and to the right leading on into the interior of the house. Cuba’s current reality intrudes here only in the form of the green corrugated plastic that covers part of the courtyard, dripping steady separated streams of rainwater.

Those who owned only one property, their home, at the time of the 1959 revolution were allowed to keep it. For those with a home big enough – ironically the middle classes which, despite belonging to them, Castro most detested – it has become not just a roof over their head but a major means of support. Toleration of foreign tourism has provided an alternative economy with access to hard currency. The communist paradise of Castro today has a vital private sector on the side.