Smuggler Nation (24 page)

Authors: Peter Andreas

Tags: #Social Science, #Criminology, #History, #United States, #20th Century

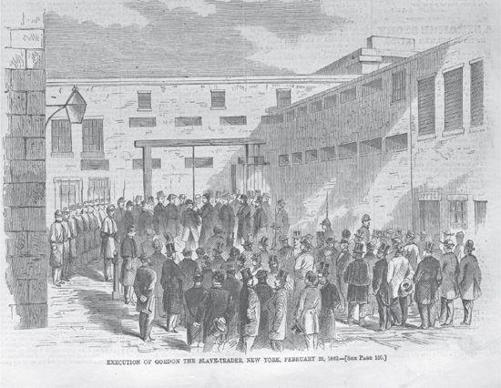

On February 21, 1862, Nathaniel “Nat” Gordon was the first and only American ever hanged for illicit slave trading—more than four decades after the passage of the federal law making slave trafficking the equivalent of piracy and punishable by death. Gordon’s sentence generated much interest not only because of its severity but also because it was so unprecedented. It was a powerful political statement as well for the new administration of Abraham Lincoln.

17

Just a few years earlier, another slave trafficker, Captain James Smith, had been found guilty, only to be pardoned by President James Buchanan.

18

But with the outbreak of the Civil War the political climate radically changed. Lincoln rejected multiple pleas for leniency in the case, including a petition for mercy signed by eleven thousand New Yorkers.

19

So even though on paper America’s antislave-trade prohibitions certainly had plenty of teeth, there was no real bite until near the end of the transatlantic slave trade. In practice, Washington’s approach to suppressing slave trafficking was defined more by negligence and

apathy than by committed and sustained policing. Enforcement was woefully inadequate, but criminalizing the slave trade nevertheless mattered. It pushed the trade more out of sight, and therefore more out of the public mind. It signaled the government’s disapproval of the trade without requiring a substantial commitment of federal resources or undermining of its support for domestic slavery. It added to the growing social stigma associated with international slave trafficking. And it created an enormously lucrative opportunity for illicit slavers and their accomplices.

Figure 8.1 “Hanging Captain Gordon.”

Harper’s Weekly

, March 8, 1862. Nathaniel Gordon was the first and only American slave trader executed for violating the federal crime of slave trafficking (John Hay Library, Brown University).

American Collusion in the Carrying Trade

The American government’s policing of the foreign slave trade was anemic, erratic, and ambivalent; the country’s illicit commercial involvement in the trade was anything but. This was especially true of northern seaports. Indeed, the United States went from being a secondary player in the international slave trade when it was legal to the leading player in the trade after it was prohibited. Criminalization ended up giving America a competitive advantage in the foreign slave trade, capturing market share as other nations grew susceptible to ever more intensive British pressure to curb their involvement.

American slave traders openly flouted the first state and federal prohibitions, considering them little more than a nuisance. Nowhere was this more apparent than in tiny Rhode Island, the first state to ban the slave trade but also the most commercially involved. In October 1787, Rhode Island abolitionists, led by Moses Brown in Providence, successfully pushed through a bill making it illegal for any citizen of the state to “directly or indirectly import or transport, buy or sell, or receive on board their vessel … any of the natives or inhabitants of any state or kingdom in that part of the world called Africa, as slaves or without their voluntary consent.”

20

The abolitionist minister Samuel Hopkins wrote with pride the next month: “Is it not extraordinary, that this State, which has exceeded the rest of the States in carrying on this trade, should be the first Legislature on this globe which has prohibited that trade? Let them have the praise of this.”

21

Moses Brown and his fellow abolitionists were also instrumental in pushing through the first federal antislave-trade law in 1794, prohibiting “the carrying on the

slave trade from the United States to any foreign place or country.”

22

The law established penalties for violators, including forfeiture of ships and steep fines.

Rhode Island slave traffickers, meanwhile, went about their business as usual. In fact, the number of ships setting sail from Rhode Island to the African coast substantially increased in the mid-1790s.

23

In Providence, John Brown not only invested in illicit slaving voyages but was the most outspoken critic of the state and federal antislave-trade laws that his abolitionist brother, Moses, passionately lobbied for. He defiantly exclaimed, “in my opinion there is no more crime in bringing off a cargo of slaves than in bringing off a cargo of jackasses.”

24

He also told Congress that restricting American participation in the international slave trade unfairly placed the country’s merchants at a competitive disadvantage. U.S. citizens, he argued, had as much a right as anyone to the “benefits of the trade,” and banning U.S. ships would do nothing to impede the trade: “We might as well therefore enjoy that trade as leave it wholly to others.”

25

In August 1797, John Brown was the first person convicted for violating the new federal antislave-trade law, receiving the relatively mild punishment of forfeiting his ship, the

Hope

(a separate trial in 1798 failed to convict him on offenses that would have also imposed substantial financial penalties). Forfeiture was a small price to pay and well worth the risk relative to expected profit, given that the value of the ship paled in comparison to the profits from the shipload of slaves John Brown had already successfully delivered abroad.

26

Moreover, even though federal forfeitures were standard practice in Rhode Island convictions, it was also standard practice for owners to simply purchase back their vessels at a deeply discounted price through rigged public auctions. Competing bids were locally frowned on, ensuring a low price—sometimes as little as ten dollars—for the original owner. Court costs for the government, meanwhile, were nearly one hundred dollars.

27

To counter this common ploy, William Ellery, the Newport customs collector, sent Samuel Bosworth, the Bristol surveyor, to participate in bidding for a seized ship, the

Lucy

, at a Bristol auction in July 1799. Well aware of the local hostility this would generate, Bosworth accepted the task “with considerable fear and trembling.”

28

The night before the scheduled auction, John Brown and the local owner of the

Lucy

paid Bosworth a visit at his home. They cautioned that it would be unwise and inappropriate for him to carry out his assigned task. He received another visit and warning the next morning. Undeterred, Bosworth headed out to the auction but was kidnapped en route and dumped two miles out of town. The

Lucy

was auctioned off as scheduled, sold to a Cuban captain who worked for the ship’s original owner.

29

The federal ban was clearly proving to be ineffective. In fact, the number of Africa-bound ships from Rhode Island reportedly tripled between 1798 and 1799, increasing from twelve to thirty-eight clearances.

30

Though slave trading was never more than a side business for John Brown, it was the core business for the DeWolf family in Bristol. The DeWolfs were allegedly the country’s leading participants in the foreign slave trade from the late colonial years to around 1820. Their ability to continue in the international flesh trade long after it had been outlawed was made possible by the complicity of the local customs inspector, Charles Collins, appointed in 1804 by Thomas Jefferson despite having served as a captain on DeWolf slaving ships. The DeWolfs and their political allies had successfully petitioned Jefferson to fire the previous inspector, Jonathan Russell. Russell bitterly complained to Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin that whereas he did not object to his own removal, he considered Collins to be a criminally inappropriate replacement given his involvement in “numerous and notorious” evasions of the law. Indeed, at the same time as Collins was being appointed customs collector he was also informed that his slave ship had successfully delivered its human cargo in the West Indies.

31

The very creation of a separate Bristol customs district came about through John Brown’s political maneuverings during his stint in Congress, allowing the DeWolfs to circumvent stricter enforcement of the Newport customs collector, Ellery.

32

Collins, who was also the brother-in-law of the slave trafficker James DeWolf, stayed on as the Bristol collector for nearly two decades. During this time, Bristol slave traders enjoyed de facto legal immunity. Africa-bound departures soared.

33

Critics were intimidated and informants silenced. When a local abolitionist dared to push for the prosecution of a slave ship, he was attacked in his sleep and had an ear sliced off.

34

Although Jefferson may very well have simply been duped into firing Russell and appointing

Collins as the Bristol collector, he took no action when later informed of the criminal consequences.

35

Collins remained collector until 1820, when President James Monroe declined to reappoint him—bringing to an end the heyday of Bristol slave trading.

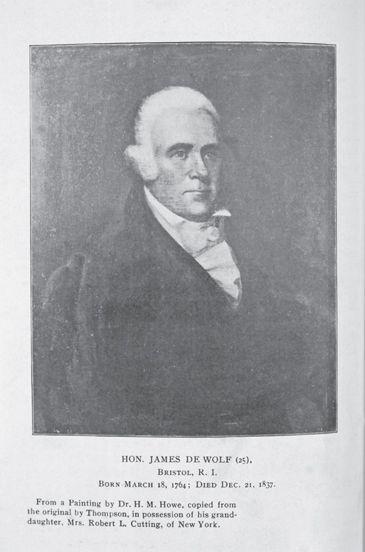

Figure 8.2 James DeWolf (1764–1837) of Bristol, Rhode Island. DeWolf may have been America’s richest slave trader, flagrantly violating state and federal antislave-trade laws (New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations).

Officially retired from slave trading, James DeWolf went on to be elected to Congress, providing political ammunition for South Carolina Senator William Smith in his 1820 speech denouncing Northern hypocrisy. “The people of Rhode Island have lately shown bitterness against slaveholders, and especially against the admission of Missouri,” Smith stated. “This, however, cannot, I believe, be the temper or opinion of the majority, from the late election of James DeWolf as a member of this house, as he has accumulated an immense fortune in the slave trade.”

36

Smith also submitted documents from the Charleston customs house showing that of the twelve thousand slaves imported

on American vessels between 1804 and 1808, almost two-thirds were brought in on Rhode Island ships.

37

Other eastern seaports also became enmeshed in the foreign slave trade, especially in later years. New York City came to be known as the world’s leading center for financing, organizing, and outfitting slaving voyages in the 1850s and early 1860s. The combination of having one of the busiest seaports in the world and a tolerant legal climate made New York an excellent cover and hub for illicit slavers. When New York Senator William Seward met opposition from New York businessmen after he proposed new legislation in 1858 to curb the slave trade, he bluntly responded: “The root of the evil is in the great commercial cities and I frankly admit, in the City of New York. I say also that the objection I found to the bill, came not so much from the slave States as from the commercial interests in New York.”

38

That same year, the

Times

of London described New York as “the greatest slave-trading mart in the world.”

39

In 1857 the

New York Journal of Commerce

editorialized, “Few of our readers are aware … of the extent to which this infernal traffic is carried on, by vessels clearing from New York, and in close allegiance with our legitimate trade; and that down-town merchants of wealth and respectability are extensively engaged in buying and selling African negroes, and have been, with comparative little interruption, for an indefinite number of years.”

40

The

New York Evening Post

even published a list of eighty-five vessels outfitted in New York Harbor from early 1859 to mid-1860 engaged in the international slave trade.

41

Cuba provided the main market. Perhaps up to 170 Cuba-bound slave voyages were organized in New York in 1859–1861; British authorities estimated that almost eighty thousand slaves were brought in during this period, with each slave selling for $1,000.

42

In 1863, the U.S. consul in Havana, Robert Shufeldt, reported: “However humiliating may be the confession … nine tenths of the vessels engaged in the slave trade are American.”

43