Smuggler Nation (8 page)

Authors: Peter Andreas

Tags: #Social Science, #Criminology, #History, #United States, #20th Century

London remained undeterred. To centralize and coordinate customs in the colonies, the British set up the American Board of Customs Commissioners, headquartered in Boston. This move—part of the Townsend Acts of 1767, which placed new duties and other restrictions on colonial trade—quickly backfired. With customs operations now centered around the activities of the American board, so too did

colonial opposition.

21

In other words, the creation of the board and its ill-advised placement in Boston—the epicenter of hostility toward the Crown—unintentionally provided a highly visible, concentrated target for colonial outrage.

22

Long accustomed to viewing compliance with trade laws as optional, colonial merchants had an allergic reaction to the arrival of the American Board of Customs Commissioners. One particularly despised commissioner, Charles Paxton, was nearly tarred and feathered; he apparently eluded his pursuers only by disguising himself as a woman and escaping through side streets.

23

Indeed, “Within eight months’ time they [the commissioners] had been forced by mob action to flee the city and take refuge in a harbor fort, protected by the guns of an English man-of-war.”

24

Appalled by the level of local opposition they found upon their arrival in the colonies in November 1767, members of the board early on concluded that “[W]e … expect that we shall find it totally impracticable to enforce the Execution of the Revenue Laws until the Hand of Government is properly strengthened.”

25

Boston merchants became increasingly outspoken in their defiance. John Hancock, one of Boston’s wealthiest shippers, even publicly declared that he would not permit customs officers to inspect his vessels. On April 7, 1768, when customs inspectors boarded one of his ships, the

Lydia

, Hancock ordered his captain not to allow them to search the cargo below deck. Shortly after this incident, another of Hancock’s vessels, the

Liberty

, arrived in Boston Harbor loaded with Madeira wine. The ship’s captain submitted paperwork to the customs house indicating twenty-five pipes of wine, but the commissioners suspected a much larger cargo. They were also, no doubt, fed up with Hancock’s bravado and eager to find cause to single him out. The evidence against Hancock was weak, based largely on a questionable account provided by an informer, but the commissioners still pushed to seize the ship. During the seizure, customs officers discovered that the

Liberty

had taken on new cargo without first receiving clearance at the customs house. This was standard practice, but it technically violated the letter of the law. The

Liberty

was condemned on a technicality.

26

The seizure of the

Liberty

on June 10 sparked a firestorm. An angry crowd hurled insults, stones, and threats at the customs officers charged with seizing the ship. Fearful that the colonists might attempt a forcible

rescue, the officers anchored the

Liberty

next to a British naval vessel. The swelling crowd then turned its anger on the commissioners, forcing them to flee to the same naval ship guarding the

Liberty

. Wary of returning to Boston, they then took refuge in the fort in Boston Harbor.

The trial of Hancock and his alleged collaborators began in October 1768 and continued until the following March. The British authorities had hoped the high-profile trial would set an example and help restore their much-tarnished authority. But their legal case proved to be thin—so much so that in the end it was simply dropped. Hancock was hailed as a hero throughout the colonies. For the British, the affair was a total fiasco.

27

In this tense atmosphere, the commissioners reported to London that they were fearful of leaving the safety of the harbor fort and returning to Boston without greater protection. The English ministry responded by dispatching troops—a provocative show of force meant to awe the colonists into submission, but one that would instead lead to bloodshed and further escalation. The British regiments arrived in September 1768; their intensely resented presence would culminate in the Boston Massacre a year and a half later. Thus, as one historian has described it, “Indirectly Hancock and his ship, the

Liberty

, had commenced a series of events leading to open revolution.”

28

In one respect, historian Clyde Barrow points out, the American Board of Customs Commissioners had been a modest success: the customs service in the colonies actually showed a profit for the first time between 1767 and 1774. The revenue generated was still much less than had been hoped, and operating costs had also risen due to greater enforcement, but it was a major turnaround.

29

This improved revenue collection, however, came at a high political cost. Through its stepped-up enforcement and implementation of the Townsend duties, the customs service became the main target of colonial anger toward the crown, increasingly in the form of mob violence.

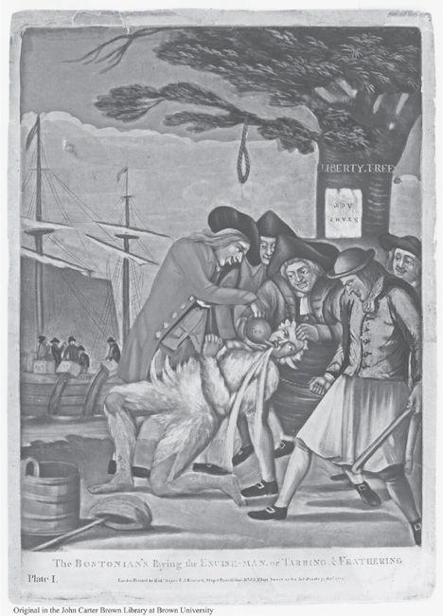

In Salem, Massachusetts, for example, customs officer James Rowe persisted in making a seizure rather than accept a bribe in 1769, and in response he was tarred and feathered, wheeled around the town in a cart, and forced to wear signs labeling him an informer.

30

The situation was equally volatile elsewhere. That same year, Providence customs

officer James Saiville “was seized while on duty.” He was “gagged; had his clothes cut from his body; was covered in turpentine and feathers from head to foot; was beaten; had dirt thrown on him; was carried about in a wheelbarrow.”

31

Further south, in November 1770, not only was a vessel seized by John Hatton, the customs collector at Salem and Cohensy in New Jersey, forcibly rescued, but Hatton was arrested and jailed for wounding one of the crewmen on the seized boat. Not giving up, Hatton then dispatched his son to try to recover the rescued vessel headed for Philadelphia. When the young Hatton discovered the vessel in the city’s harbor, the crew organized an attack in which Hatton was beaten, dragged, and tarred and feathered, and had hot tar poured into his wounds. Hatton barely survived. Without any witnesses willing to testify, the investigation into the matter was quickly dropped.

32

The head of customs in Philadelphia commented on the incident: “In short, the truth of the matter is, the hands of Government are not strong enough to oppose the numerous body of people who wish well to the cause of smuggling … What can a Governor do, without the assistance of the Governed? What can the Magistrates do, unless they are supported by their fellow Citizens? What can the King’s officers do, if they make themselves obnoxious to the people amongst whom they reside?”

33

One of the most brazen attacks on customs occurred a few years later in Rhode Island. On June 9, 1772, the Royal cutter

Gaspee

was stormed and burned late at night in Narragansett Bay. Earlier that day, the

Gaspee

had run aground while chasing a suspected smuggling vessel. Realizing it was stranded and vulnerable, local merchants, led by John Brown, quickly formed a raiding party that snuck up on the ship under cover of darkness and overwhelmed its crew. Long known as a particularly troublesome colony and a haven for illicit trade, Rhode Island more than lived up to its reputation on this particular night. After the

Gaspee

was ransacked and set ablaze, Governor Thomas Hutchinson warned London that if England “shows no resentment against that Colony for so high an affront … they may venture upon any further Measures which are necessary to obtain and secure their independence.” He concluded that if the perpetrators were not found and punished “the friends to Government will despond and give up all hopes of being able to withstand the Faction.”

34

The ministry of Lord North appointed a

commission to investigate the incident, but the inquiry generated little local cooperation and was eventually dropped. To deflect attention and criticism in the aftermath of the attack on the

Gaspee

, Providence leaders went into damage control mode: they conveniently blamed fringe elements of society and promised to look into the incident, while well aware that the ringleaders included some of the town’s most prominent merchant elites.

35

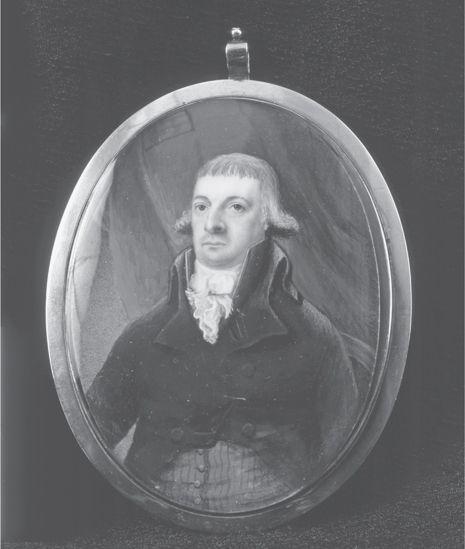

Figure 2.1 John Brown (1736–1803), prominent Rhode Island merchant, privateer, slave trader, and politician. Brown led the attack on the British customs schooner

Gaspee

in 1772 and later was the first American tried and indicted for violating the federal government’s 1794 Slave Trade Act. He was also one of the founders of the university that bears his name. Painting by Edward Malbone 1794 (New York Historical Society).

As provocative as the

Gaspee

affair was, London showed some restraint in its response. The same was not true, however, in what became known as the “Boston Tea Party,” which served as not only a lightning rod for colonial opposition but also a trigger for British overreaction. On the

evening of December 16, 1773, a group of irate Boston colonists, some thinly disguised as Mohawk Indians, boarded three ships of the British East India Company and for the next three hours proceeded to dump 342 chests of tea into Boston Harbor—cheered on by the crowds watching from the dock. The incident had a polarizing effect. Samuel Adams and other colonial opposition leaders celebrated and defended the “party” as a principled protest. Startled and appalled when news of the incident reached London, British politicians pushed to take a hard line. London retaliated by closing the port of Boston and introducing a series of punitive measures known as the Coercive Acts. This proved to be a tipping point: both the Boston Tea Party and the punishing British response served as a catalyst for mobilizing opposition throughout the colonies.

Figure 2.2 Burning of the British customs schooner

Gaspee

in Narragansett Bay, 1772. Painting by C. Brownell (Granger Collection).

What provoked this incident that proved to be such an historic turning point? The Boston Tea Party is remembered in the popular imagination as a protest against taxes. But it actually had more to do with smuggling interests than tax burdens. Relatively low-priced tea supplied to the colonies by the British East India Company—which had been given a monopoly on tea imports—undercut the sale of smuggled Dutch tea, which at that point dominated the local market in violation of the Townsend duty on tea. “The Smugglers not only buy cheaper in Holland but save the 3d duty,” complained Governor Thomas Hutchinson.

36

He speculated that three-quarters of the “prodigious consumption in America” was illicitly imported, and in another letter wrote, “We have been so long habituated to illicit Trade that people in general see no evil in it.”

37

In the summer of 1771 Hutchinson guessed

that more than 80 percent of the tea consumed in Boston was smuggled in.

38

No doubt many colonists found the granting of monopoly trade rights to the British East India Company irksome. But most threatened were the economic interests of those colonial merchants who had invested heavily in the illicit Dutch tea trade and enjoyed wide profit margins. As one economic historian puts it, “The ‘Party’ was organized not by irate consumers but by Boston’s wealthy smugglers, who stood to lose out.”

39