Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect (12 page)

Read Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect Online

Authors: Matthew D. Lieberman

Tags: #Psychology, #Social Psychology, #Science, #Life Sciences, #Neuroscience, #Neuropsychology

BOOK: Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect

13.11Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Others studies have suggested that our brains crave the positive evaluation of others almost to an embarrassing degree.

Keise Izuma conducted a study in Japan in which

participants in the scanner saw that strangers

had characterized them as

sincere

or

dependable

.

Having someone we have never met and have no expectation of meeting provide us with tepid praise doesn’t seem like it would be rewarding.

And yet it reliably activated the subjects’ reward systems.

When participants in this study also completed a financial reward task, Izuma found that the social and financial rewards activated the same parts of the ventral striatum, a key component of the reward system to a similar degree.

Sally Field really was speaking for us all when she expressed her delight at being liked by others.

Not only are we sensitive to the positive feedback of others but also our reward system in the brain responds to such feedback far more strongly than we might have guessed.

If positive social feedback is such a strong reinforcer, why don’t we use it more often to motivate employees, students, and others?

Why isn’t it part of our employee compensation plans at work, for example?

A kind word is worth as much to the brain in terms of rewards as a certain amount of money.

So why isn’t it part of the economy, like all other goods we assign a financial value to?

The answer is that it isn’t yet part of our theory of what people find rewarding.

We don’t understand the fundamentally social nature of our brains in general and the biological significance of social connection in particular.

As a result, it’s hard for us to conceptualize how positive social feedback will be reinforcing within the most primitive reward system of our brains.

When I was in graduate school at Harvard working in Dan Gilbert’s lab, I remember Kevin Ochsner telling me that I didn’t praise the younger students in lab enough.

I remember thinking, “Who am I to praise or not to praise?

I’m a fifth-year graduate student who has yet to publish a single paper.

My praise is meaningless.”

Of course, Kevin was right.

If a stranger saying we are “dependable” activates the reward system, imagine what praise from a boss, a parent, or even an unaccomplished slightly older graduate student will do.

Of course, we all know that praise is a good thing, as long as it isn’t too unconditional, but until very recently, we had no idea that

praise taps into the same reinforcement system

in the brain that enables cheese to help rats learn to solve mazes.

And positive

social regard is a renewable resource.

Rather than having less of something after using it, when we let others know we value them, both parties have more.

Varieties of Reward

Though it might not seem so, money is a social reward—a reward for doing something of social value.

Everyone who earns a salary is paid to do something that others want done, whether the person receiving the money is the biggest rock star in the world or her accountant.

We all get paid to provide a service, not because we are doing what we want to do.

Some of us are lucky enough to enjoy our work, but that is not why we get paid.

When I was a new professor, I used to joke that if I were in charge, most academics wouldn’t be paid at all because most of us enjoy it enough that we would do it for free.

But we are paid because of the value of our work to others.

Money is a social currency, just not an altruistic social currency.

Rewards can be divided

into primary and secondary reinforcers.

Things that satisfy our basic needs like food, water, and thermo-regulation are known as

primary reinforcers

—they are an end in themselves, and the brain comes prepared to recognize these things as reinforcing without needing to be taught about them.

When in a deprived state, all mammals work hard to obtain these primary rewards.

Secondary reinforcers

are things that are not initially rewarding in and of themselves but become reinforcing because they predict the presence or possibility of primary reinforcers.

If a rat is placed in a maze and has to choose whether to turn left or right in order find the cheese, it will do its best to learn where the cheese will be so it can up its odds of getting the reward each time.

If the cheese is randomly placed during each trial, the rat cannot learn.

But if the experimenter always places a little patch of red paint on the side of the maze leading to the cheese, the rat will learn

to follow the signs.

The red patch is not intrinsically rewarding

, but if it consistently predicts where the cheese will be, the rat’s reward system will start responding to the red patch.

Money is the world’s most ubiquitous secondary reinforcer.

You can’t eat or drink it, and you would need an awful lot of it to keep you warm.

Yet obtaining money is the best way adults can guarantee that their other basic needs will be met—it puts food on the table and a roof over their heads.

Although money doesn’t intrinsically satisfy any needs, it is often viewed as the most desirable reward of all.

Perhaps getting money is like getting several rewards at once, because we can imagine countless ways to spend it.

So where does social regard fall within this typology of reward?

It is probably both a primary and a secondary reinforcer.

When your boss tells you how impressed he is with your work on the Davidson merger, it is easy to imagine this praise leading to a larger Christmas bonus.

But studies like Izuma’s suggest that social regard might be a primary reinforcer as well.

The brain’s reward system is activated as a result of such praise, even from strangers who have no control over that Christmas bonus.

Evolution built us to desire and work to secure positive social regard.

Why are we built this way?

One possible explanation is that when humans, or other mammals, get together, work together, and care for one another, everyone wins.

Given that other living creatures are the most complex and potentially dangerous things in our environment, a push from nature to connect with others in our species, an urge to please one another, increases our chances of reaping the benefits of group-based living.

Working Together

In the Pixar film

A Bug’s Life

, an easygoing colony of ants is terrorized by a group of Mafioso grasshoppers demanding an unseemly cut of the colony’s food in return for their “protection.”

Early in the movie, the eventual protagonist, an ant named Flik, stands up to

the mob boss and is quickly put in his place; he is no match for the grasshoppers.

The rest of the film focuses on the ants and other bugs learning to work collectively to defeat their tormentors.

Predictably, after multiple failures, the ants succeed in ridding themselves of the grasshoppers by working together.

While depicted anthropomorphically through the life of ants, it is a classic story of human courage and cooperation.

When we pool our resources, we can do more together than we can alone.

Cooperation is one of the things that makes humans special.

Many species cooperate, but as Melis and Semmann write, no other species comes close “to the scale and range of [human] cooperative activities.”

Compared to the rest of the animal kingdom,

humans are supercooperators

.

Why do humans cooperate so often?

Why do they cooperate at all?

The easiest answer is that people cooperate when they stand to benefit directly from the cooperative effort.

In

A Bug’s Life

, the ants band together to defeat the grasshoppers, so that they will no longer have to give away their food.

Similarly, two college students taking the same class may study for an exam together because each believes they will improve their test scores more with their combined effort than by studying alone.

There are other kinds of cooperative helping where the self-interested payoffs are less conspicuous.

The

principle of reciprocity

is one of the strongest

social norms we have.

If someone does you a favor, you feel obligated to return the favor at some point, and with strangers we actually feel a bit anxious until we have repaid this debt.

This is why car salesmen will always offer you a cup of coffee.

By performing a small favor for you

, they render you indebted to them, and the only thing you can really do for them in return is buy a car, yielding a commission worth far more than that cup of coffee.

Obviously a free drink alone doesn’t always lead to a purchased car, but it can nudge people in that direction.

Similarly, we may cooperate with someone in such a way that, in the short run, we give up more than we gain, but with the expectation that we will benefit through reciprocity in the long run.

More interesting are the kinds of motivations that must be present when cooperating clearly reduces the benefit to oneself in the long run.

Behavioral economists use

a game called the

Prisoner’s Dilemma

to illustrate this phenomenon.

In this game, two players have to decide whether to cooperate with each other or not.

How much money players earn depends on the combination of their decisions.

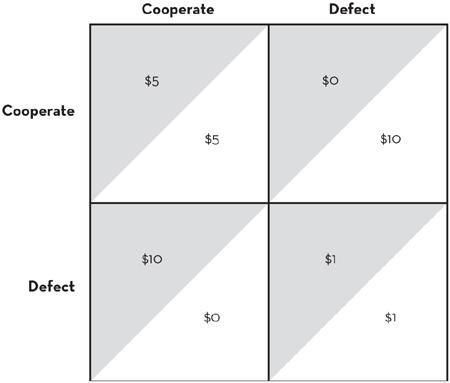

Imagine there is $10 at stake for you and another player (see

Figure 4.2

).

If you both choose to cooperate, you each get $5, and if you both choose not to cooperate, you each get $1.

So far the decision to cooperate is easy.

However, if one of you chooses to cooperate and the other chooses not to, the noncooperating defector gets the entire $10, and the cooperator gets nothing.

In other words, if you choose to cooperate, there’s a chance you’ll look like a chump as the other person takes all the money.

Figure 4.2 Prisoner’s Dilemma Contingencies

Assume that you have never met the other player, do not get to discuss your decision with the other player, and will have no further interactions with that person after this one game.

What do you do?

If you want to make the most money and you assume the

other person will cooperate, you should defect (because you’ll earn $10 instead of $5).

If you assume the other person will defect, then you should still defect (because you’ll earn $1 instead of nothing).

Regardless of what the other person does, you make more money by defecting.

Nevertheless, multiple studies have shown that under these conditions,

people still choose to cooperate

more than a third of the time.

The Axiom of Self-Interest

How can we explain why folks cooperate

, ensuring that they will earn less money and their partners will earn more?

Are players who know the contingencies but still choose to cooperate irrational?

If we believe nineteenth-century economist Francis Edgeworth’s contention that

“the first principle of economics

is that every agent is actuated only by self-interest,” then this cooperative behavior does seem irrational.

And Edgeworth is hardly alone in putting selfishness front and center (and alone) as the basic motivation behind all of our actions.

It’s a common refrain.

The eighteenth-century philosopher David Hume proposed that political systems should be based on the assumption that a man has

“no other end, in all his actions

, than his private self-interest.”

A century earlier, the philosopher Thomas Hobbes first formalized this account, charging that

“every man is presumed to seek

what is good for himself naturally, and what is just, … accidentally.”

This basic assumption is

known as the

axiom of self-interest.

A belief that self-interest guides everything we do leaves no room to explain the individuals who chose to cooperate, other than to suggest that they were irrational or they misunderstand the instructions.

But how would this axiom explain the following findings?

In some variants of the Prisoner’s Dilemma, Player A is informed of Player B’s decision before making his own.

Not surprisingly, when Player A is told that Player B has chosen to defect, Player A always

decides to defect (assuring himself of $1 instead of $0).

What is surprising, though, is that

when Player A is told that Player B has chosen to cooperate, Player A increases his own rate of cooperation from 36 to 61 percent.

Player A is willfully choosing to earn $5 instead of $10, when the supposedly rational thing to do would be to defect.

If you were going to play the game repeatedly with the same player, such a choice might be consistent with the axiom of self-interest.

By using your choice to create a reputation as a cooperator, you can hope to earn $5 in future rounds of the game, rather than have your partner start defecting, thus leaving you with less over time.

But in the studies I’ve described, the game is a one-time occurrence, and thus creating a reputation has no benefit.

The only reasonable explanation is that

in addition to being self-interested

, we are also interested in the welfare of others as an end in itself.

This, along with self-interest, is part of our basic wiring.

Other books

The Dragon's Appraiser: Part One by Viola Rivard

One Moment in Time by Lauren Barnholdt

Whispers (Argent Springs) by Stark, Cindy

On the Edge by Catherine Vale

The Guardian's Wildchild by Feather Stone

Sacrificed to Ecstasy by Lacy, Shay

A Fatal Stain by Elise Hyatt

Raising Steam by Terry Pratchett

The Handmaid's Tale by Margaret Atwood

Outcast by Oloier, Susan