Socrates (2 page)

Authors: C. C. W. Taylor Christopher;taylor

Chapter 1

Introduction

Socrates has a unique position in the history of philosophy. On the one hand he is one of the most influential of all philosophers, and on the other one of the most elusive and least known. Further, his historical influence is not itself independent of his elusiveness. First we have the influence of the actual personality of Socrates on his contemporaries, and in particular on Plato. It is no exaggeration to say that had it not been for the impact on him of the life and above all of the death of Socrates Plato would probably have become a statesman rather than a philosopher, with the result that the whole development of Western philosophy would have been unimaginably different. Then we have the enduring influence of the figure of Socrates as an exemplar of the philosophic life, of a total moral and intellectual integrity permeating every detail of everyday life and carried to the heroic extreme of steadfastness in the face of rejection and ignominious death. But the figure of Socrates the protomartyr and patron saint of philosophy, renewed in every age to speak to that age’s philosophical condition, is the creation, not of the man himself, but of those who wrote about him, above all of Plato. It is Plato’s depiction of the ideal philosopher which has fascinated and inspired from his day to ours, and if we attempt to penetrate that depiction in the quest for the historical Socrates we find the latter as elusive as the historical Jesus of nineteenth-century New Testament scholarship.

Again, there are two main reasons for this elusiveness (a situation which reinforces the scriptural parallel). First, Socrates wrote nothing himself, and secondly (and consequently), after his death he quickly became the subject of a literary genre, that of ‘Socratic conversations’ (

Sōkratikoi logoi

), in which various of his associates presented imaginative representations of his conversations, representations which focused on different aspects of his personality and style of conversation in accordance with the particular interests of the individual author. Plato’s dialogues and the Socratic writings of Xenophon are the only examples of this genre to survive complete, while scraps of other Socratic writings, notably those of Aeschines, survive through quotation by later authors. This literature will be discussed in more detail below. For the moment it should be emphasized that, while each of Plato, Xenophon, and the rest presents his own picture of Socrates in line with his particular purpose, each presents a picture

of Socrates

. That is to say, it would be a serious distortion to think of any of these writers as creating a free-standing figure, for example, of the ideal philosopher, or the model citizen, to which figure its author attaches the name ‘Socrates’. Socrates is, indeed, depicted by Plato as the ideal philosopher, and in my view that depiction involves at various stages the attribution to him of philosophical doctrines which Plato knew that Socrates never maintained, for the very good reason that Plato had himself invented those doctrines after Socrates’ death. But Socrates was in Plato’s view the appropriate paradigm of the ideal philosopher because of the kind of person Plato believed Socrates to have been, and the kind of life Plato believed him to have lived. In the sense in which the terms ‘fiction’ and ‘biography’ designate exclusive categories, ‘Socratic conversations’ are neither works of fiction nor works of biography. They express their authors’ responses to their understanding of the personality of a unique individual and to the events of that individual’s life, and in order to understand them we must seek to make clear what is known, or at least reasonably believed, about that personality and those events.

1. Bust of Socrates – a Roman copy of an original made shortly after Socrates’ death.

Chapter 2

Life

While Socrates’ death can be firmly fixed by the record of his trial to the early spring of 399

BC

(Athenian official year 400/399), there is an unimportant dispute about the precise date of his birth. The second-century

BC

chronicler Apollodorus (cited by the third-century

AD

biographer Diogenes Laertius (2.44)) assigns it with unusual precision (even giving his birthday) to early May 468 (towards the end of the Athenian official year 469/8) but Plato twice (

Apol

. 17d,

Crito

52e) has Socrates describe himself as seventy years old at the time of his trial. So, either Socrates, still in his sixty-ninth year, is to be taken generously as describing himself as getting on for seventy, or (as most scholars assume) the Apollodoran date (probably arrived at by counting back inclusively seventy years from 400/399) is one or two years late. The official indictment (quoted by Diogenes Laertius) names his father, Sophroniscus, and his deme or district, Alopeke (just south of the city of Athens), and in Plato’s

Theaetetus

(149a) he gives his mother’s name as Phainarete and says that she was a strapping midwife. That may well have been true, though the appropriateness of the name (whose literal sense is ‘revealing virtue’) and profession to Socrates’ self-imposed task of acting as midwife to the ideas of others (

Tht

. 149–51) suggests the possibility of literary invention. His father was said to have been a stonemason, and there is a tradition that Socrates himself practised that trade for some time; the fact that he served in the heavy infantry, who had to supply their own weapons and armour, indicates thathis

circumstances were reasonably prosperous. His ascetic life-style was more probably an expression of a philosophical position than the reflection of real poverty. His wife was Xanthippe, celebrated by Xenophon and others (though not by Plato) for her bad temper. They had three sons, two of them small children at the time of Socrates’ death; evidently her difficult temper, if real, was not an obstacle to the continuation of conjugal relations into Socrates’ old age. An unreliable later tradition, implausibly ascribed to Aristotle, mentions a second wife named Myrto, marriage to whom is variously described as preceding, following, or bigamously coinciding with the marriage to Xanthippe.

Virtually nothing is known of the first half of his life. He is reported to have been the pupil of Archelaus, an Athenian, himself a pupil of Anaxagoras; Archelaus’ interests included natural philosophy and ethics (according to Diogenes Laertius ‘he said that there are two causes of coming into being, hot and cold, and that animals come to be from slime and that the just and the disgraceful exist not by nature but by convention’ (2.16)). The account of Socrates’ early interest in natural philosophy put into his mouth in Plato’s

Phaedo

(96a ff.) may reflect this stage in his development; if so, he soon shifted his interest to other areas, while any influence in ethics on the part of Archelaus can only have been negative.

It is only with the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War in 432, when he was already over 35, that he begins to emerge onto the historical scene. Plato several times (

Apol

. 28e,

Charm

. 153a, and

Symp

. 219e ff.) refers to his military service at the siege of Potidaea on the north Aegean coast in the opening years of the war, and in the last of these passages has Alcibiades enlarge on his courage in combat and his remarkable endurance of the ferocious winter conditions, in which he went about wearing his ordinary (by implication, thin) clothing and barefoot. The latter detail is of interest in linking Plato’s portrayal of Socrates with our only unambiguously independent evidence for his personality and activity, the portrayal of him in fifth-century comedy. Some lines of the comic dramatist Ameipsias, quoted (according to most scholars, from his lost play

Connus

, which was placed above Aristophanes’

Clouds

in the competition of 423) by Diogenes Laertius, refer to his physical endurance, his ostentatiously simple clothing, and his going barefoot ‘to spite the shoemakers’; and shoelessness is twice mentioned as a Socratic trademark in

Clouds

(103, 363). Another comic poet, Eupolis, referred to him as a beggarly chatterbox, who didn’t know where his next meal was coming from, and as a thief, another detail reproduced in Aristophanes’ caricature (

Clouds

177–9). By the 420s, then, Socrates was sufficiently well known to be a figure of fun for his eccentrically simple life-style and for his loquacity. But, while his individual characteristics undoubtedly provided welcome comic material, it is as representative of a number of important and, in the dramatist’s eyes, unwelcome trends in contemporary life that he figures in the only dramatic portrayal to have survived, that in Aristophanes’

Clouds

.

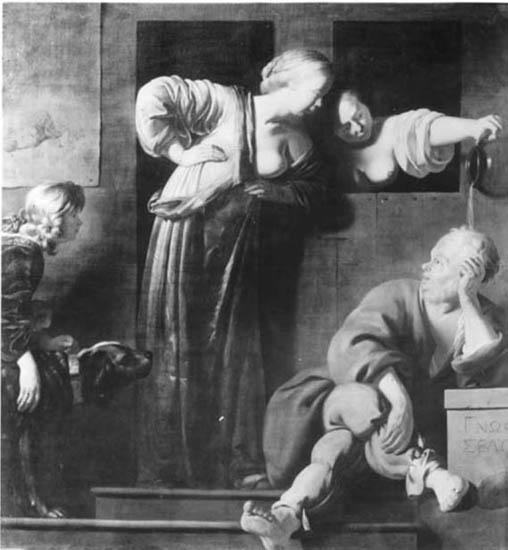

2. A comical representation of Socrates with his ‘two wives’, by the 17th-century Dutch painter Caesar Boethius van Everdingen (1606–78). The stone on which Socrates is leaning bears the maxim ‘Know Thyself’, inscribed on the temple of Apollo at Delphi, which was treated in antiquity as a Socratic slogan.

The crucial point is well summarized by W. K. C. Guthrie:

[W]e can recognize in the Socrates of the

Clouds

at least three different types which were never united to perfection in any single person: first the Sophist, who teaches the art of making a good case out of a bad one; secondly the atheistic natural philosopher like Anaxagoras; and thirdly the ascetic moral teacher, ragged and starving through his own indifference to worldly interests.

1

In the play Socrates presides over an institution where students pay to learn techniques of chicanery to avoid paying their debts; this is called ‘making the weaker argument defeat the stronger’, a slogan associated with the sophist Protagoras, and the combat between the two arguments, in which the conventional morality of the stronger (also identified as the Just Argument) succumbs to the sophistry of the weaker (the Unjust Argument), is a central scene of the play. But, as

well as a teacher of sophistry, the Socrates of the

Clouds

is a natural philosopher with a special interest in the study of the heavens, a study which involves rejection of traditional religion and its divinization of the heavenly bodies in favour of the new deities: Air, Aither, Clouds, Chaos, Tongue, and ‘heavenly swirl’, which displaces Zeus as the supreme power of the universe. Naturally, the new ‘religion’ provides the metaphysical underpinning of the sophistical immoralism, since, unlike the traditional gods (who are not ‘current coin with us’, as Socrates says (247–8)), the new deities have no interest in punishing wrongdoers. At the conclusion of the play Socrates’ house is burnt down specifically as a punishment for the impious goings-on which have taken place in it; ‘investigating the position of (peering at the arse of) the moon’ and ‘offering wicked violence to the gods’ (1506–9) are two sides of the same coin.

By 423, then, Socrates was sufficiently well known to be caricatured as a representative of the new learning as it appeared to conservatively minded Athenians, a subversive cocktail of scientific speculation and argumentative gymnastics, with alarming implications for conventional morality and religion. Such a burlesque does not, of course, imply detailed knowledge on the part of either dramatist or audience of the doctrines or activities either of Socrates or of contemporary intellectuals (though a number of commentators have been impressed by parallels between details of the doctrines ridiculed in

Clouds

and some of the doctrines of the contemporary natural philosopher Diogenes of Apollonia). But both dramatist and audience must have had some picture (allowing for a great deal of exaggeration, oversimplification, and distortion) of what sort of thing Socrates on the one hand and ‘intellectuals’ like Protagoras and Diogenes on the other were getting up to. We have to ask what Socrates had done by 423 to create that picture.

It is totally implausible that he had actually done what Aristophanes represents him as doing, namely, set up a residential institution for

scientific research and tuition in argumentative techniques, or even that he had received payment for teaching in any of these areas. Both Plato and Xenophon repeatedly and emphatically deny that Socrates claimed scientific expertise or taught for money (

Apol

. 19d–20c, 31b–c, Xen.

Mem

. 1.2.60, 1.6.5, and 1.6.13), and the contrast between the professional sophist, who amasses great wealth (

Meno

91d,

Hipp. Ma

. 282d–e) as a ‘pedlar of goods for the soul’ (

Prot

. 313c), and Socrates, who gives his time freely to others out of concern for their welfare and lives in poverty in consequence (

Apol

. 31b–c), is a central theme in Plato’s distancing of the two. It is impossible to believe that Plato (and to a lesser extent Xenophon) would have systematically engaged on that strategy in the knowledge that Socrates was already notorious as exactly such a huckster of learning, but not at all difficult to believe that comic distortion depicts him as such when he was in fact something else. What else? One thing every depiction of Socrates agrees on is that he was, above all, an arguer and questioner, who went about challenging people’s pretensions to expertise and revealing inconsistencies in their beliefs. That was the sort of thing that sophists were known, or at least believed, to do, and, for a fee, to teach others to do. It was, therefore, easy for Socrates, who was in any case conspicuous for his threadbare coat (

Prot

. 335d, Xen.

Mem

. 1.6.2, DL 2.28 (citing Ameipsias)), lack of shoes, and peculiar swaggering walk (

Clouds

362, Pl.

Symp

. 221b), to become ‘That oddball Socrates who goes about arguing with everyone and catching them out; one of those sophist fellows, with their damned tricky arguments, telling people there aren’t any gods but air and swirl, and that the sun’s a redhot stone, and rubbish of that kind.’ Rumours of his early interest in natural philosophy and association with Archelaus and (possibly) of unconventional religious attitudes may have filled out the picture, which the comic genius of Aristophanes brought to life on the stage in 423.