Socrates (3 page)

Authors: C. C. W. Taylor Christopher;taylor

Plato mentions two other episodes of active military service at Delium in Boeotia in 424 (

Apol

. 28e,

Lach

. 181a, and

Symp

. 221a–b) and at

Amphipolis on the north Aegean coast in 422 (

Apol

. 28e). His courage during the retreat from Delium became legendary, and later writers report that he saved Xenophon’s life on that occasion. As Xenophon was about six years old at the time the incident is obviously fictitious, doubtless derived from Alcibiades’ account of Socrates’ heroism in the earlier campaign at Potidaea, which included his saving Alcibiades’ life when he was wounded (

Symp

. 220d–e). At any rate, it is clear that exceptional physical courage was an element in the accepted picture of Socrates, along with indifference to physical hardship, a remarkable capacity to hold his liquor (

Symp

. 214a, 220a, 223c–d), and, in some accounts, a strongly passionate temperament, in which anger and sexual desire were kept under restraint by reason (Cicero,

Tusculan Disputations

, 4.37.80, cf. Pl.

Charm

. 155c–e,

Symp

. 216d) (or were not, according to the hostile Aristoxenus). We are given a detailed picture of his physical appearance in middle age in Xenophon’s

Symposium

, where he describes himself as snub-nosed, with wide nostrils, protruding eyes, thick lips (5.5–7), and a paunch (2.19), which exactly fits Alcibiades’ description of him in Plato’s

Symposium

as like a satyr or Silenus (215b, 216d; cf. Xen.

Symp

. 4.19). (For the snub nose and protruding eyes see also

Tht

. 143e.) Two scholia (i.e. marginal notes in manuscripts, probably written in late antiquity) on

Clouds

146 and 223 say that he was bald, but there is no contemporary authority for this, and it may be an inference from his resemblance to a satyr, as satyrs were often represented as bald.

Nothing more is known of the events of his life till 406, when there occurred what was apparently his only intervention, till his trial, in the public life of Athens. Following a naval victory the Athenian commanders had failed to rescue survivors, and the assembly voted that they should be tried collectively, instead of individually as required by law. Most offices being at that time allocated by lot, Socrates happened to be one of the committee who had the task of preparing business for the assembly, and in that capacity he was the only one to oppose the unconstitutional proposal. (That is the version of events

reported at

Apol

. 32b–c and by Xenophon in his

Hellenica

(1.7.14–15), but in his

Memorabilia

Xenophon twice (1.1.18, 4.4.2) gives a different version, in which Socrates was the presiding officer of the assembly during the crucial debate, and ‘did not allow them to pass the motion’ (which, given that the motion was in fact passed, must be understood to mean ‘tried unsuccessfully to prevent the motion being put’

2

).)

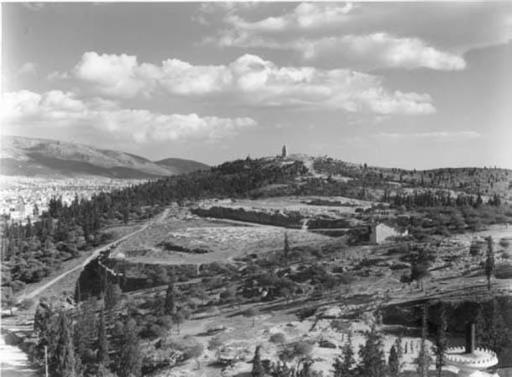

3. The Pnyx, the meeting-place of the Athenian assembly: a view from the Observatory.

On the final defeat of Athens in 404 the democratic constitution was suspended and power passed to a junta of thirty who, nominally appointed to revise the laws, soon instituted a reign of terror in which thousands were killed or driven into exile. This lasted for eight months until the tyranny was overthrown in a violent counterrevolution and the democracy restored. Socrates had friends in both

camps. Prominent among the Thirty were his associates Charmides and Critias (both relatives of Plato), both of whom were killed in the fighting which accompanied the overthrow of the tyranny, while among the democrats his friends included the orator Lysias and Chaerephon, both of whom were exiled and active in the resistance to the tyrants. Socrates maintained the apolitical stance which he had adopted under the democracy. He remained in Athens, but when the tyrants attempted to involve him by securing his complicity in the arrest of one Leon of Salamis he refused to co-operate ‘but just went home’ (

Apol

. 32d, cf. Xen.

Mem

. 4.4.3). There is no hint of political opposition, but the same simple refusal to be involved in illegality and immorality which had motivated his stand on the trial of the naval commanders. There is no evidence as to whether he took any part in the overthrow of the tyranny; the silence of Plato and, even more significantly, Xenophon on the issue suggests that he did not.

Trial and Death

Some time in 400 or very early in 399 an obscure young man named Meletus (

Euthyph

. 2b) brought the following indictment against Socrates:

Meletus son of Meletus of Pitthos has brought and sworn this charge against Socrates son of Sophroniscus of Alopeke: Socrates is a wrongdoer in not recognizing the gods which the city recognizes, and introducing other new divinities. Further, he is a wrongdoer in corrupting the young. Penalty, death.

Two others were associated in bringing the charge: Lycon, also unknown, and Anytus, a politician prominent in the restored democracy. After a preliminary examination (mentioned at the beginning of Plato’s

Euthyphro

) before the magistrate who had charge of religious cases, known as the king, the case came to trial before a jury of 500 citizens in the early spring of 399.

4. Remains of the Royal Stoa or

Stoa Basileios

, the headquarters of the King Archon, who was in charge of religious affairs. Socrates came to this building to be formally charged with impiety.

No record of the trial survives. In the years following various authors wrote what purported to be speeches for the prosecution or the defence; two of the latter, by Plato and Xenophon, survive and none of the former. After speeches and production of witnesses by both sides the jury voted for condemnation or acquittal. According to

Apol

. 36a the vote was for condemnation by a majority of sixty, presumably approximately 280 to 220. Once the verdict was reached each side spoke again to propose the penalty, and the jury had to decide between the two. The prosecution demanded the death penalty, while (according to Plato) Socrates, after having in effect refused to propose a penalty (in

Apol

. 36d–e he proposes that he be awarded free meals for life in the town hall as a public benefactor), was eventually induced to propose the not inconsiderable fine of half a talent, over eight years’ wages for a skilled craftsman (38b). The vote was for death, and

according to Diogenes Laertius eighty more voted for death than had voted for a guilty verdict, indicating a split of 360 to 140; Socrates’ refusal to accept a penalty had evidently alienated a considerable proportion of those who had voted for acquittal in the first place.

Execution normally followed very soon after condemnation, but the trial coincided with the start of an annual embassy to the sacred island of Delos, during which, for reasons of ritual purity, it was unlawful to carry out executions (

Ph

. 58a–c). Hence there was an interval of a month (Xen.

Mem

. 4.8.2) between the trial and the execution of the sentence. Socrates was imprisoned during this period, but his friends had ready access to him (

Crito

43a), and Plato suggests in

Crito

that he had the opportunity to escape, presumably with the connivance of the authorities, to whom the execution of such a prominent figure may well have been an embarrassment (45e, 52c). If the opportunity was available, he rejected it. The final scene is immortalized in Plato’s idealized depiction in

Phaedo

. The method of execution, self-administration of a drink of ground-up hemlock, was less ghastly than the normal alternative, a form of crucifixion, but medical evidence indicates that the effects of the poison were in fact much more harrowing than the gentle and dignified end which Plato depicts. According to Plato his last words were ‘Crito, we owe a cock to Asclepius; pay it and don’t forget’ (

Ph

. 118a). Asclepius was the god of health, and the sacrifice of a cock a normal thank-offering for recovery from illness. Perhaps those were in fact his last words, in which case it is interesting that his final concern should have been for a matter of religious ritual. (This was an embarrassment to rationalistic admirers of Socrates in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.) But the idealized quality of Plato’s description makes it plausible that the choice of these words was determined rather by dramatic appropriateness than by historical accuracy. On that assumption the point may have been to give a final demonstration of Socrates’ piety, but that would have been more appropriate to Xenophon’s portrayal than Plato’s. A recent ingenious suggestion is that the detail refers back to Phaedo’s

statement (59b) that Plato was absent from the final scene through illness. The offering is in thanks for Plato’s recovery, and marks Plato’s succession as Socrates’ philosophical heir. This degree of self-advertisement seems implausible; the older view (held by Nietzsche among others) that the thanks is offered on behalf of Socrates himself, in gratitude for his recovery from the sickness of life (cf. Shakespeare’s ‘After life’s fitful fever he sleeps well’), seems more likely.

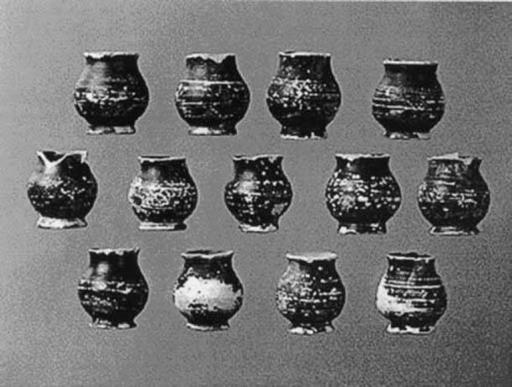

5. Thought to have contained poison for executions, these small containers were found in a cistern in the state prison.

The lack of any record of the trial makes it impossible to reconstruct precisely what Socrates’ accusers charged him with. The explicit accusations cited above are sufficiently vague to allow a wide variety of conduct to fall under them, and in addition Athenian legal practice sanctioned the introduction of material which, while strictly irrelevant to the letter of the charges, might be expected to influence the jury for or against the defendant. An ancient tradition holds that the real ground for the condemnation of Socrates was political, namely, his

supposed influence on those of his associates who had become notorious for anti-Athenian and anti-democratic conduct, above all Alcibiades and Critias; thus the orator Aeschines asserted categorically that ‘You, Athenians, killed the sophist Socrates because he was seen as having educated Critias, one of the thirty who overthrew the democracy’ (

Against Timarchus

173 (delivered in 345

BC

); cf. Xen.

Mem

. 1.2.12–16). Given the notoriety of Alcibiades, Critias, Charmides, and other known associates of Socrates such as Phaedrus and Eryximachus, both of whom had been involved (along with others of the Socratic circle) in a celebrated religious scandal in 415

BC

, it would have been very odd had the prosecution not brought up their misdeeds to defame Socrates as a corrupter of the young. An amnesty passed in 403 did indeed prevent people from being charged with crimes committed previously, but that was no bar to citing earlier events as indicative of the defendant’s character. It seems, then, virtually certain that the charge of corrupting the young had at least a political dimension. It would not follow that the specifically religious charges were a mere cover for a purely political prosecution, or that the alleged corruption did not itself have a religious as well as a political aspect. We have seen that in the 420s Aristophanes had made Socrates a subverter of traditional religion, whose gods are displaced in favour of ‘new divinities’ such as Air and Swirl, and a corrupter of sound morality and decent education. It is clear from his

Apology

that Plato thought that some of this mud still stuck in 399, and I see no reason to doubt that he was right. Though the evidence of a whole series of prosecutions of free-thinking intellectuals, including Protagoras and Euripides, in the late fifth century is gravely suspect, it is likely that Anaxagoras was driven from Athens by the threat of prosecution for his impious declaration that the sun was a red-hot stone, and the care which Plato takes in the

Apology

to distance Socrates from Anaxagoras (27d-e) indicates that he saw that case as looming large in the attack on Socrates.