Somebody's Heart Is Burning (25 page)

Rod became more affectionate than ever, clinging to my hand, sitting on my lap, hanging onto my legs. I sat with her sometimes from afternoon till evening, stroking her hair and singing. Her presence brought up my latent mothering instincts. I loved children, always had, the touch and feel and smell of them. They opened my heart in a way that nothing else could. There was a part of me that wanted children of my own, yearned for them with a longing so fierce it stopped my breath. Michael, too, had wanted children passionately. He had even tried to persuade me, on occasion, to play a little Russian roulette between the sheets.

“I can’t do it, Michael,” I’d said.

“Why not? You’re great with kids. Look at my nieces and nephews. They adore you.”

“I adore them, too.”

“Well then?”

“Because. I’m not ready. You know that. I want to do things. I’m not . . . stable enough yet. If I got pregnant now, I wouldn’t forgive myself. Or the child.”

Michael shuddered. “Don’t say that,” he said.

Now, with Rod on my lap, I was hard-pressed to remember what “things” I had to do that were so important. I wanted to squeeze her little body close to me, to bury my nose in her oiled and braided hair. Maybe I’d made a mistake. Maybe having children was exactly what I needed, the catalyst that would toss me headfirst into the clear cold pool of my own happiness. The ultimate wake-up call. Maybe. Maybe not. Unfortunately, I couldn’t take a trial run.

One evening, I sat next to Brigitte on her bed while she worked the sleeping Lidia’s hair into tight little braids. Rod had already been put down for the night.

“Lidia never lets me do this when she’s awake,” Brigitte explained.

I watched her fingers fly, dipping into oil, then sectioning, braiding, sectioning again.

“I don’t love my husband,” she said to me. “I used to love him, but now I don’t. He goes with other women.”

“How do you know?” I asked.

“I’ve seen the woman. My friend has pointed her out to me.” She made a disgusted face. “It makes me sick. And he doesn’t give me money.”

I looked around. “How do you buy things?”

“Oh, he pays for food, you know. School things. But anything for me, my clothes, my hair, I have to get it for myself. But he won’t let me get a job! He wants me to have more children.” She pulled another face.

I watched her fingers layer the braids into overlapping arches.

“As soon as I find someone else,” she continued, “I’m going to divorce him. I just have to find someone first. I don’t want to go around, going on dates. A woman isn’t safe that way. But I must hurry, before another baby comes. Can you find an American husband for me?”

“I can’t even find one for myself,” I joked.

“I want an old man,” she said. “Young men are too complicated. I want one who’ll appreciate me. I’ll give you a picture of me to give him and he can send his picture, and if we like each other, then he’ll send me the plane ticket and I’ll come.”

I pointed out that the visa might still be a problem.

“He’ll get it for me,” she said. “If he’s hot, he’ll do it.” She took her hands from Lidia’s hair and ran her palms up and down the sides of her body, over her breasts, arms, thighs. She closed her eyes. “An old man, who’ll treat me well.”

I said nothing. After a moment, she opened her eyes and went back to her hair sculpture. Lidia started for a moment, opened her eyes, and whimpered. Then, seeing her mother, she closed them again and drifted back to sleep.

“What about Lidia and Rod?” I asked. “What will they do if you go to the U.S. and marry some old fart?”

She shrugged impatiently. “Their father will take them. I will send money. It will be better for them.”

I looked down at the sleeping baby. “If I . . . If I had children like yours,” I said, “I could never leave them.”

Anger crossed Brigitte’s face, and I was immediately ashamed. Who was I to lecture her? Single and childless, I was a veritable poster child for the transient lifestyle.

“They’ll be okay,” she said.

We sat in silence, Brigitte’s hands resting on Lidia’s braided head.

“In your city, will you show me around?” she asked later that night, as we lay side by side on her white-sheeted bed under the gauzy canopy of the mosquito net.

“Of course,” I said, eager to reestablish our intimacy. “We’ll go dancing together, go shopping, to the movies.”

“Oh yes,” she said, “yes, that’s it. I’ll be in the movies. You’re an actress, aren’t you?”

I nodded, “But not in movies. On the stage.”

“I’ll do movies,” she said. “That’s the way to make money.”

I laughed, and she turned her head sharply toward me.

“It’s not that easy,” I said.

“Oh, but I can do it!” she said, and in the dark, I could feel the motion of her hands stroking the sides of her body, her head thrown back. “I can do the movies like that, the love scenes . . . I know how to do it.” She stopped abruptly. “Of course, if I had a husband, he wouldn’t let me. On my own, I could make some money.”

“Your husband probably wouldn’t stop you. In the U.S., it’s normal for women to work. Most women work.”

“Oh yes?” she said. “Good.”

When I got back from the Malian embassy the next afternoon, passport and visa in hand, I found Brigitte in the smoke-filled kitchen, waving a large stick at Nyanga. The wispy girl cowered in the corner, wailing with fear.

“She’s bête!” Brigitte shrieked, when she saw me, using the French word that means both “stupid” and “beast.”

“What? What happened?”

“

Bête!

I had some mayonnaise—did you see the mayonnaise? I bought it—it was supposed to last until Easter—and yesterday she served it

all

to the people who were here.

All

of it.

Il faut

économiser.

I don’t earn the money here, it’s my husband who earns the money. What’s he going to say? He will blame me, he will blame

me,

and then . . . Stupid beast!” She held the stick above her head, her face livid. The girl sobbed loudly, pressing herself into the wall as though she hoped to push through it and disappear. My eyes teared in the heavy smoke.

Behind Brigitte, Constantin appeared in the doorway, sucking on his fingers, a guilty smile on his face. Afraid his presence would further escalate things, I gestured sharply with my head, and he scampered off. I approached Brigitte slowly, holding out my hand for the stick.

“Everyone makes mistakes,” I said.

“The same stupid mistakes, again and again. I will beat her now. Never a word, this girl, never a sound, but she is trouble, she is bad!”

“She’s not bad. We all make mistakes,” I said again, evenly.

“I made the mistake, staying here with these stupid girls. I could be in America, with Rod, Peace Corps. There is a machine that washes, a machine that makes the food!”

“That’s not her fault, Brigitte. She’s just a child. Look at her, she’s terrified. Please. I’ll buy you more mayonnaise. A whole new jar.”

Brigitte looked at me as though I were a stranger, an alien being she was seeing for the first time. I tried to smile, but my lips wouldn’t do the trick. In the corner, the girl moaned. Out in the courtyard, I heard Constantin’s cackling laughter.

How desperate we humans are,

I thought.

How our hearts burn,

feeding on their own desire as if it were tinder.

Slowly, as though awakening from a dream, Brigitte lowered the stick.

At eleven o’clock that night, Brigitte and I sat on the couch in the living room, drinking beer. It was my goodbye party. Brigitte got up, went to the tape recorder, and put in a tape—a funky, bluesy groove. She pulled me up, and we started to dance. After about twenty minutes, I collapsed back onto the couch, my head swimming. Brigitte kept dancing, her eyes closed. I stared at her, mesmerized by the extreme grace of her bulky frame. Her hips seemed to move independently of her upper body, which hovered above them, regal and still. Her behind taunted the beat, tantalized it, waiting till the last possible instant, till I thought she wouldn’t make it, couldn’t, then it snapped into place, twitching and popping like corn in hot oil.

Over the rhythmic thump of the music, I heard Rod’s voice coming from the bedroom, soft and plaintive. “Mama. Mama. Mama. Mama.”

I longed to go to her, but what good would it do? Tomorrow I’d be gone, and besides, she wasn’t mine. I don’t know whether Brigitte heard her or not. She just kept dancing.

14

Sand Angel

In Ghana, funerals are parties, with drumming and dancing all night

long. The older the deceased, the bigger the bash. T-shirts commemorate

the prominent ones, with inscriptions like “In ever-loving memory of

Mercy Aidoo, alias Nanna,” silk-screened on the front and “Rest in

Peace” on the back. As one guy told me, “When a young man dies, it

is a sad thing. But when an old man dies, it is just natural, so we figure

we might as well entertain ourselves.” Others put it more delicately:

“We rejoice that the person has lived so very long and well.”

Maybe this blunt attitude toward death is part of why the average

West African seems so much happier than the average American. Perhaps the constant awareness that death could drop in makes people more

fully inhabit their lives. My Ghanaian friends strenuously protest the

comparison. “We are desperate here!” they say. Nevertheless, I dare anyone to walk down the streets of Accra and then San Francisco, observing

the faces, and tell me the Ghanaians aren’t happier. You might say that

smiling is just a habit, a cultural mannerism, but I think it goes beyond

that. These are not empty smiles. The approach to daily life is humorous and exuberant, even in difficulty, like popping a whole chili pepper

into your mouth and relishing the burn.

For better or worse, Katie’s absence had freed me to travel to whatever out-of-the-way place struck my fancy. One such place was the legendary city of Timbuktu. Its illustrious history as a trade center and seat of higher learning was enough to capture anyone’s imagination, but even more intriguing to me was the boat trip up the Niger River. According to my guidebook, people along the river were living much as they had for thousands of years. The more sedentary groups inhabited fishing villages, while the nomadic tribes set up temporary camps, pulling up stakes and moving with the migration patterns of the fish. Even before her illness, Katie had been reluctant to make the journey. If anything happened, she’d said, we’d be too far from anywhere to get decent medical care. Now that she was gone, there was no obstacle to me hopping on a boat.

Before I left Ghana, I discussed the matter with a bikini-clad English expatriate I encountered by the pool at the Accra Novotel. The Novotel was the most expensive hotel in the city, practically the only place in Ghana where you could pay European-scale prices for everything from soap to sandwiches. On hot days, I occasionally splurged on the three-dollar fee to spend an afternoon by the blue waters of its heavily chlorinated pool.

“You don’t want to go there!” the expatriate said in horror, reclining in a white plastic lawn chair while she rubbed cocoa butter onto her sleek, tan legs. “Timbuktu’s a ghost town! There’s nothing to see. It’s not the great trading mecca it once was. No camel caravans laden with gold. Just a few beleaguered beasts with feathers on their heads, and an army of guides waiting to mob you every time you step outside your hotel. Besides, how good is your French? Mali is Francophone, you know.”

Her equally sleek and sun-bronzed French boyfriend opened his eyes and chimed in. “Sand,” he said flatly. “A lot of sand. Sand in the hair, sand in the eyes, sand in the bread you eat,

crunch crunch.

” He wrinkled his nose and mimed picking grains of sand from his mouth.

“And the boat rides!” the woman continued, waving her hand in front of her nose in horror. “You know how sometimes a trip is really grueling, but when you finally arrive, you say, ‘Well, it was hell, but I’m glad I did it?’ ” She paused for emphasis. “This is not one of those trips. It’s just hell.”

The Niger is the third largest river in Africa, after the Nile and the Congo. If you include its delta—the surrounding wetlands created by the river’s sediment—it’s the largest in the world. Starting in Guinea, the river enters Mali just below the capital city of Bamako. It heads northeast across Mali until it reaches the edge of the Sahara at Timbuktu, then turns due east. Shortly thereafter it shifts toward the southeast in a great arc, passes through Niger and Nigeria, and empties into the Atlantic Ocean. In its entirety, the river basin overlaps nine countries.

I decided to catch the boat to Timbuktu in Mopti, a major trading center about 200 miles southwest of the legendary port. On my way to Mopti, I stopped for a few days in the city of Ségou, where I saw the river for the first time.

It was after dark when I made my way through the dusty streets to the banks of the Niger. I’d arrived from Ghana in the late afternoon, found a guesthouse, eaten, and showered. The day had been overcast, and the night was now very dark, with neither stars nor moon showing through the thick cover of clouds. A few streetlights and glimmers from windows illuminated my way. When I reached the river I saw a vast stripe of darkness that was more like an absence than a presence. On the bank a group of men huddled around a fire. Coming closer, I saw the fire’s light reflected in the water. Then I saw

pirogues

— the long, slender canoes of Mali—floating in darkness, their silhouettes supple bows against the reflected light.

It’s hard to explain what I felt then, or why. The water’s fathomless darkness seemed to beckon, as though it would draw me in. I’d never thought of myself as a spiritual person, and yet I’d spent my adult life seeking

something.

In that moment I felt that the river would change me, though I had no idea how.

The city of Ségou was a charming blend of old and new. Donkey carts, bicycles, mopeds, and taxis rattled side by side down the wide colonial avenues. Decaying mansions lined the boulevard, laundry hanging from their wrought-iron trellises, their yards full of banana trees. Alongside the great river, the earth had regained its color again, and red dirt like the kind I’d seen in Ghana replaced the pale desert dust.

Mali felt like another world. Here, the turbans of the desert began to appear. Old men walked the streets, their light-colored

bou-bous

reaching almost to the ground. The walled alleys made me feel as if I were in Morocco again. Hidden houses, hidden lives.

The Niger by day was a green expanse, striped with dark currents. The rocky beach was littered with bleached bits of paper and plastic. On my second day in Ségou I sat on a cement promontory overlooking the beach for much of the afternoon, observing the goings-on. Below me, women washed clothes, dishes, and their own bodies in the river. Some beat the clothes on the rocks, slapping, twisting, and wringing, while others scrubbed pots and pans with sponges made from the dry brown fiber of weeds. One woman sang a lyrical, slightly plaintive song in a high, nasal voice. The tone was pure and unadorned, beautiful in its openness—a bright free sound offering itself to the world.

Later, a group of teenage girls gathered on the beach, singing upbeat songs in brassy voices. They were playing a game. They stood in a three-quarter circle, holding hands, as one girl at a time separated from the chain, stepped back, then ran and hurled her body forward against the linked arms of the others. Red Rover, we used to call it, except these girls didn’t form teams. For them it wasn’t about competition, apparently, but about the exhilaration of hurtling your body into space and being caught and held.

Throughout the day, as I perched on my cement outpost, skinny children approached me, their faces smeared with dried snot and pale with dust. They wore oversized torn clothes and held tin cans or calabashes in their outstretched hands. They mumbled unintelligible strings of words in sugary voices, smiling vacant, ingratiating smiles.

From what I could see, these begging children were the poorest people I’d encountered on this trip. In Ghana I’d seen poverty, malnutrition even, but never such forlorn, naked hunger. The expressions on the children’s faces chilled me, and I remembered that Mali, once a wealthy empire, was now one of the poorest countries in the world. I distributed what money I had on me, then shook my head apologetically and turned out my empty pockets until they wandered away.

Halfway between the capital city of Bamako and the desert gateway of Timbuktu lies Mopti. The city of Mopti was originally built over several islands, which were later connected with dykes and landfill. In the fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth centuries, when Timbuktu was a great commercial center and seat of higher learning, Mopti was little more than a village. Now Timbuktu has fallen into decay, and Mopti houses the Niger River’s most vibrant port.

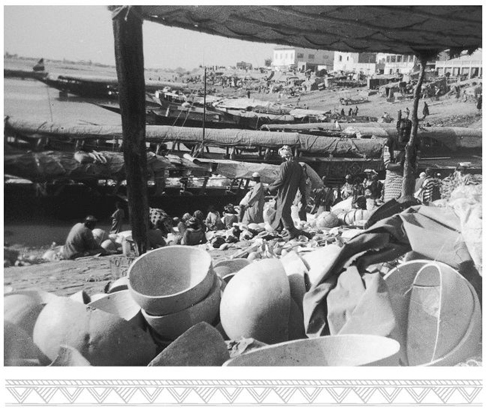

The port of Mopti is a sweeping expanse of pebble beach bustling with trade. In the packed riverside market, people hawk boat tickets, mats, cloth, blankets, and food for the journey. Others sell jewelry, leather goods, amber, and masks. Tablets of salt, also for sale, glow like enormous ice cubes in the afternoon sun. Women in bright cloth wraps with babies on their backs and men in

bou-bous

and turbans mill about, buying and bartering at top volume. Fabrics dyed in indigo, made in Guinea or by the Dogon people of southern Mali, are popular in Mopti. Standing at the top of a sandy slope, I looked down on a full range of blue and purple garments, from pale lavender to deepest navy, interspersed with splashes of other vivid fabrics, including decoratively painted rust-colored mudcloth.

I finally located Mohammed Hammed, an elderly gentleman in an electric blue turban who sold boat tickets to Timbuktu. He was standing on a wooden crate, next to a stand overflowing with oranges.

“You must go to the airport!” he shouted in French when he saw me.

“I don’t want the plane; I want the boat!” I shouted back. I’d been warned by other vendors that Mohammed Hammed was hard of hearing.

“The steamboat, it is not in season!”

“I don’t want the steamboat. I want the

pinasse

!”

In the wet season, tourists rode large steamboats to Timbuktu, but in the dry season you had only two options for river travel: the

pirogue

(canoe), or the

pinasse

(motorized canoe).

He stared. “You want to ride the pinasse? With all the African traders—black people—with their goods? No private cabin. No ‘comfort-of-home.’ ”

“Yes, that’s it. The ancient trade route,” I nodded vigorously. “No comfort! Crowded, smelly, difficult. That’s what I want.”

He shook his head in disbelief. “Well . . . Let me see if I have a ticket . . .” He made a show of shuffling through a small stack of papers. “Hup! One left.

Six mille CFA.

Six thousand francs.”

“Oh, come on! I saw you selling that guy a ticket for half that!” I indicated a portly African man who’d just walked away with a ticket and a bag of grain.

“You people take up space for two. You are not used to travel like we do. Will you be able to sleep like this?” He crouched, hugging his knees to his chest.

“Forty-five hundred?”

“Five thousand.”

“Including food?”

“Oh all right,” he said, with a

you-drive-a-hard-bargain

sigh.