Somebody's Heart Is Burning (23 page)

“You must talk more quietly; you’re talking very loudly.” He eyed a portly man at the next table, who was staring at us with unmasked curiosity. “I was just making several options available to you,” he whispered. “You never know what a person wants to do. I said, do you want to go to the concert tomorrow, to the museum, shall I go with you to the market? You said no. I said you are very interesting, can I take you to bed? You said no to that, too. I said all right. I was only giving you choices.”

My head was spinning from the beer, and I started to laugh. The day’s heat and exhaustion lifted off me, and I felt giddy and weightless. So what if I couldn’t find my hotel that night? I’d surely find it in the morning, when it was light.

Perhaps I am a

genie,

I thought,

full of hidden powers,

and the thought made me feel sexy, reckless. Something moved inside, not unlike the sensation before an impulse purchase, a rash, against-my-better-judgment stirring, a heart-knock of desire. I was lonely, too— why not indulge once in a while? Whose outdated ethic governed me? What was I defending, and why? Here was Jimmy, a physically stunning man, and vital, creative, alive. I could almost feel the heat of his hands against my body, the long smooth journey of my fingers down his back. Oh God, it had been so long . . .

I leaned forward and kissed his lips.

“You want to know what I am?” I asked softly. I was about to follow it up with something flirtatiously ironic, when Jimmy quickly scooted back his bench and stood up.

“Please,” he said, “The bartender, he knows all the hotels. He will help you. Please be kind. Don’t watch me. Don’t follow me. Please.”

And Jimmy was down the street and around the corner before I could tell him that of all my roadside suitors he was the lucky winner—that I was no genie at all, just a tipsy human female ready to step off her pedestal and seek a little comfort far from home.

13

She Kept Dancing

Sitting on buses and

tro-tros

, I find myself repeatedly telling strangers

the story of my life. Sometimes, hearing myself talk, I feel as if I’m doing

it more for my own benefit than for the hapless individual sitting beside

me, listening with such polite attention. Some need seems to drive my

narration, as if through the telling I’m constructing a self-image that I

can anchor myself to and believe in. I want the events to be linear and

the lessons cumulative, building on each other like Legos: this led me

here, and I learned this, and then I was here, and I was lost, and I found

this.

Life, of course, was never so orderly. It was more like my long hair

used to be after a ride in the open back of a truck: an ungovernable tangle. Growth wasn’t like that either. Growth happened when I wasn’t

looking. It happened later, after I’d given up hope. And love wasn’t like

that: so transparent and unequivocal, a balance sheet of pros and cons.

Life was life and love was love. All the explanations came later.

I hadn’t noticed Brigitte until we pulled up to the curb in downtown Ouagadougou and she leaned over and tapped me on the shoulder. “If you don’t have a place to stay during your visit,” she said with breathless timidity, “you are welcome in my house.”

I was used to sudden changes in plans and to West Africans’ amazing, nearly overwhelming hospitality. I hadn’t planned to stop off in Burkina Faso’s sprawling capital, but I suddenly realized I needed to apply here for my Malian visa. It would be just my luck to arrive at the border and get turned away. Besides, after spending a largely sleepless night at the side of the road while our

tro-tro

driver went in search of a tire, I was in no mood to coninue traveling. My cream-colored T-shirt and olive skirt had turned road-dust gray, and my shorn hair—the only part of my body retaining any natural oils—was plastered to my scalp. Something new and odd was happening with my body, which for days had produced the sensation of sweating, though no actual moisture appeared. I felt like a kettle that rattles and shakes, but never quite manages to sing.

I stood guard over Brigitte’s cloth-tied bundles while she used the phone box outside the upscale

Hôtel de l’Indépendance

to call her husband. Oceans of

motos

swerved around me. The air was thick with dust and exhaust, whipped about by the

harmattan

’s harsh gusts. The sunlight seemed to rob the landscape of depth, leaving it two-dimensional, like a painted set. Even with sunglasses on, the glare knit a hard ache behind my eyes.

Driving north from Ghana, the terrain had grown gradually drier. The color of the dirt had shifted, little by little, from red and brown to tan to almost white. The streets, buildings, and grass of Ouaga (as I soon came to call it) appeared washed out, as though they had been dipped in a bucket of bleach.

Brigitte was in her mid-twenties. She had a plump figure and a perky, impish face with round, shiny cheeks and eyebrows that leaped and danced when she spoke. She had managed to stay astoundingly clean on the journey from Bobo, where she’d gone to visit her cousin. Her bright orange and green print dress still looked freshly pressed. A matching cloth wrapped her head.

“I’m bringing a friend home,” I heard her say. She paused for emphasis, then added, “a

white

friend,” her voice simmering with excitement.

An expensive taxi ride took us from wide, heavily trafficked downtown boulevards lined with stately buildings to a gravel-paved neighborhood on the outskirts of town, where solid cinderblock houses with clean-swept dirt yards alternated with vacant lots filled with rubble. Goats nosed around in the debris, munching on garbage. Not the pygmy goats of Ghana, but lanky Burkina Faso goats, with drooping ears and tails, and doleful, basset hound eyes.

Brigitte lived in one of the cinderblock rectangles with her husband—a midlevel customs official—their three children, and two servant girls. In the open-air bathroom, a mud wall separated the neatly swept section where a board covered a hole in the ground from the area where you carried your bucket of water to bathe. With a television, boom box, and telephone inside the house, it was a solid middle-class home.

It was love at first sight for me and little Rod. She stood shyly at the gate with her three middle fingers in her mouth, twisting her upper body back and forth as the taxi pulled up. As I swung my bulky pack out of the roof rack, she was already at my side, and I swerved off-balance to avoid hitting her. When I flopped onto the couch in the tiny living room, she came and sat silently on my lap.

Rod was five years old and had silky skin the color of fresh coffee grounds, kept creamy by her mother’s daily application of shea butter. Her small face was a perfect oval with grave, wide-set eyes so dark you couldn’t separate iris from pupil, and pouty, beautifully shaped lips which often hung slack in the unselfconscious gape of childhood. She seldom spoke, but always stayed within a few steps of me, often slipping a hand into mine as I sat writing or talking in the yard.

“This one’s too quiet,” Brigitte said, holding Rod at arm’s length and brushing dust off her pink skirt with a brusque hand. “Here comes the smart one.” Her face lit up with a smile as a chubby two-year-old careened through the doorway with a stocky teenager following a step behind.

“Lidia already speaks French, don’t you?” Brigitte said to the little one.

“Tu parles français?”

“Oui!”

the baby shouted, and Brigitte laughed with delight. She barked a command at the teenager, who rushed out into the yard. “I’ve told her to get water for your bath,” Brigitte told me. Brigitte and I spoke French with each other, while she usually spoke to the children and servants in her native Mossi. She turned back to the crowing Lidia.

“This one,” she said, smiling, “this is my girl.”

Her son Constantin came home a few hours later, dragging a book bag behind him, his school uniform covered with mud.

“Tintin!” Brigitte called sharply. “Did you greet our guest?”

He slid to a halt in front of me, a nine-year-old bundle of kinetic energy: hands, knees, and feet all trembling to go.

“Pleased to meet you,” he murmured, sneaking a glance from lowered eyes.

“My pleasure,” I said.

He flashed me a smile, dropped his bag in front of the couch, and took off running, out the door and through the gate.

“Change your clothes,” Brigitte shouted as he tore around the corner. “Did you see him? That one is bad,” she said, sighing and shaking her head. “Bad.”

Rod and Constantin shared a bedroom with two teenage servant girls, Nyanga and Yolan, while Lidia slept in a crib in her parents’ bedroom. I shared the large bed with Brigitte. I never met her husband, who arrived home that night after we went to bed, slept on the couch, and left early the next morning on a business trip. When I asked Brigitte about him, she simply shrugged her shoulders.

“He’s not mean,” she said.

I was struck by the difference in appearance between Brigitte’s children and the two servants. I knew that it was common in West Africa for middle-class people to have live-in servants, but this was the first time I’d witnessed it firsthand. While the two little girls had neatly braided hair, clean dresses in appropriate sizes, and sandals on their feet, Nyanga and Yolan walked around in faded sacklike prints, barefoot, their hair in fuzzy plaits that looked as though they hadn’t been touched in weeks.

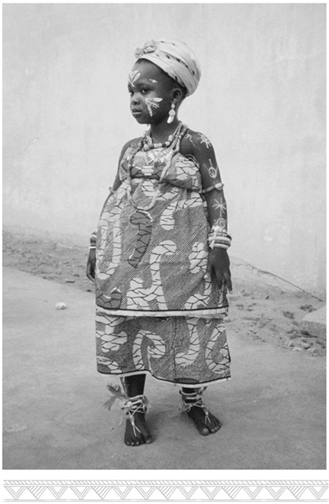

Yolan, the older girl, was seventeen years old, tall and robust, her affable face drawn in broad, clean lines. The other girl, Nyanga, was sixteen, according to Brigitte, but looked twelve. She stood about four foot ten, with slim hips and the barest hint of breasts. Her face was an impassive mask, eyes and lips locked in an expression of perpetual blankness. She looked as though she’d been through a war, and who knows? Maybe she had.

I never heard Brigitte speak a gentle word to these girls. If she spoke to them at all, it was to bark out commands, often adding the words “lazy” or “stupid” at the end. Yolan took this in stride, her sense of herself secure and unflappable, but the shouts seemed to hit Nyanga’s small body like blows. At every insult she flinched, and her face grew more determinedly blank.

When I asked Brigitte if Nyanga and Yolan had ever been to school, she said no. They were simple village girls, she told me; their families could not afford it. When I asked her what these village girls were doing in the city, she shrugged.

“The big one’s parents have died, and her family cannot keep her. Her uncle knew my husband in the army; he asked him to help. The other girl came with her. She is very ‘shhhhh.’ ” She made a zipping motion with her lips. “No one learns a word from her.” She shrugged. “They are lucky to have employment. Many such girls end up selling themselves to whichever man walks down the street.”

I wanted to speak to Brigitte about her treatment of them, but I didn’t know how, and I was wary of making things worse. I contented myself with indirect tactics, openly praising Nyanga and Yolan for their cooking, their washing, the care they took of the children. When I did this, Yolan giggled in embarrassment and Nyanga flashed a shy smile that completely transformed her appearance. Smiling, she revealed a classic African beauty, with her strong, narrow chin, high forehead, wide nose, and full lips.

Sometimes Brigitte regarded me strangely, as though suspicious of my intent.

“Don’t you think it’s a good idea to praise people when they do something well?” I asked cautiously.

“Oh yes,” she said absently. “When someone does well you must tell him so.”

Once Nyanga spilled water on the floor as she carried a bucket outside for my bath. After reprimanding her severely, Brigitte shook her head. “These girls,” she said, “they are lazy because I do not beat them.”

“They don’t look lazy to me,” I said. “They seem to work very hard.”