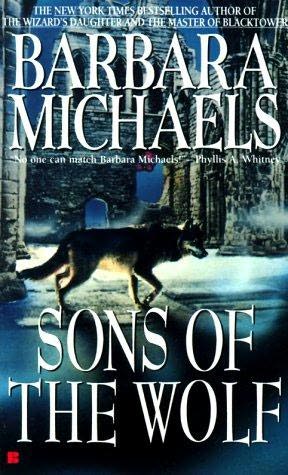

Sons of the Wolf

Authors: Barbara Michaels

Sons of the Wolf

Barbara Michaels

March 29, 1859

This morning I stood before the glass and looked at my face.

It has been a long time since I indulged in that vanity -if vanity it could be called. Black hair, straight and coarse as a horse's mane, brows black and threatening, a skin so swarthy that I fear Grandmother's unpleasant comments about my Italian mother are correct-there may be Moorish blood somewhere in that family tree. My coloring will win no crown of beauty in this land of pink complexions and flaxen curls, and the shape of my features is no more encouraging. I know what a physiognomist would say about them: the brow too high, too wide for a woman's, the nose too strong, the chin a square, uncompromising block. The mouth is wide and generous. But generosity, if that sort, is not a virtue prized by gentlemen-at least lot in their wives and daughters.

The high-collared, long-sleeved black dress deadened my skin; I scowled at it, and my ominous eyebrows dipped like little black crows. I hated both the black color and the hypocrisy it represented. My grandmother was dead. But he had hated me since the very moment of my birth. And ever since I had been old enough to understand that hate and the reason for it, I had returned the sentiment with a vigor that did my character and my Christian upbringing little credit. If I had dressed to suit my feelings, I would have blazed forth in crimson and gold.

As I stood scowling at myself the unsightly vision in the glass was obscured. Ten small fingers clasped themselves over my eyes and a sweet voice caroled in my ear, "Guess who it is!"

"Who else could it be?" I answered rudely and pulled the little hands away. The wrists were as delicate as those of a child; my own long fingers more than circled them. Over my shoulder, reflected in the glass, was Ada's face.

She must have been standing on tiptoe to reach so tall, for normally the top of her shining yellow head just reaches the bridge of my nose. She had tried to confine her curls, but they would break loose, a cascade of ringlets and waves and curls that resisted the sober black ribbon. The color of death, which is so hideous on me, only purified the delicate pallor of Ada's face; she looked even younger than her seventeen years. Now her blue eyes were wide with hurt affection, and her mouth was puckered into a pink rosebud of distress. She looked as sweet and winsome, and about as intelligent, as a Persian kitten. And, as always, guilt at my unkindness overwhelmed me. I turned and put my arms around her.

"I'm sorry, darling," I said.

She gave me a hearty hug in return; for all her delicate looks, there is nothing frail about Ada's constitution.

"It doesn't matter, dearest Harriet. I came on you too suddenly. You were thinking of-of dear Grandmother."

She is a creature of volatile moods: first hurt, then affection; then the blue eyes swam with sudden easy tears and the little chin quivered.

"Nothing of the sort," I replied-too sharply, for one tear slipped loose and flowed down the curve of Ada's nose. I made my voice more gentle as I went on. "If I was thinking of Grandmother, I assure you those thoughts don't deserve your tender consideration."

"She was always kind," Ada murmured, dabbing at her eyes with a lacy handkerchief.

"To you, perhaps-in her way. But you are her favorite daughter's favorite child and you look just like the well-bred young man of fortune she picked to be her daughter's husband. Whereas I-"

Ada's eyes sparkled. She glanced guiltily over her shoulder. The room was empty; it was my own bedchamber and, now that Grandmother was dead, no one would enter it without knocking first. But Ada has a childish love of mystery. She spoke in a thrilling whisper.

"Harriet. . . . Now that Grandmother is-is gone. . . . Oh, I have always wanted to know! What did your father do that made her so bitter toward him?"

"If you wanted to know, why didn't you ever ask me? I would have told you; there was nothing of which I am ashamed."

"But-but-Grandmother said it must never be spoken of."

"Yes, although she spoke of it herself, in hints and sly allusions, which made it worse than it was. And you never dared violate her commands, did you? No . . . come, Ada, don't cry. Darling, I am sorry! I will tell you all. It was nothing, really-nothing except an imprudent marriage against a dictatorial old woman's wishes. But that was the ultimate crime, for her."

"How can you speak so, when she is still . . ." Ada's hand made a fluttering gesture and I was reminded, with a sudden shock, that the mortal part of my grandmother was still in the house. Downstairs in the darkened library, surrounded by flowers . . . how she would have hated those sweet waxy lilies, she who had never allowed a fresh flower in the house! I laughed, to Ada's shocked surprise, and leaned forward in my chair to pat her hand.

"Our parents, as you know, were brother and sister," I said, trying to make the story simple enough for easy understanding. "Children of our grandmother. So we are cousins."

"Sisters," said Ada softly, and bounced from her chair to give me a quick kiss.

"Now sit down and be still," I said, pretending to frown at her, "or you will not follow my lecture. We are cousins by blood, if something dearer by affection. My father was the elder, as well as the only son. He was a gay, handsome fellow and Grandmother's pride; but, alas, he had inherited her arrogance and pride as well as-they say-her handsome looks. She had arranged a suitable marriage for him; but while he was on his Grand Tour, in Rome he met a young Italian peasant girl and married her. He didn't tell his mother until after the deed was done; he knew, I suppose, that she would have done anything, moral or immoral, to prevent the match."

"Your mother must have been very beautiful!"

I laughed and touched my cheek.

"According to Grandmother I am very like her. So you see it must have been her charm and wit, rather than her beauty, that won my father."

Ada bounced at me with hugs and kisses and protestations; I had to scold her again before I could go on.

"When Grandmother heard of the marriage, she was furious. She told my father that not a penny of the inheritance he had anticipated would be his. His father-our grandfather-had left him a small amount of money, to be given to him on his twentieth birthday. On this, and on what he could earn by the work of his own hands, he and his bride had to live. If he ever showed his face again at the door of his home-so his affectionate mother informed him-she would have the servants whip him away."

"How terrible!" Ada leaned forward, cheeks pink with excitement. "How could she do such a wicked thing?"

"She would fight anything that threatened her authority and her pride of lineage," I answered bitterly. "Her mother's name, as she never tired of reminding us, was Neville; she always believed that her ancestors were of that noble northern house. 'A Neville was once Queen of England, my dears.' " My voice was savage as I mimicked the voice that would never again taunt me.

"Yes, yes, I know. But to disinherit her own son-"

"They say," I remembered, "that it hurt her grievously. It was after that that she became so biting and withdrawn. And he did not suffer. He had no time for that. The climate of Rome, so healthful in summer, is deadly in winter. He died not long after I was born."

"Then you do not remember him?"

"No."

"Poor Harriet! And your poor mama!"

"How can I mourn him when I never knew him?" I asked reasonably. "I do remember my mother-just a little-as a soft warm voice singing sentimental Italian songs. And as a pair of flashing black eyes and a hard brown hand-I was a very bad child!"

Ada shook her head reproachfully.

"You pretend to have no sentiment, Harriet. But I know you better than that."

"How can I feel sentiment for a pair of ghosts? They are no more than that to me. They did nothing for me except bring me into the world. Before he died, my father, like any well-bred fool, had spent every penny of his little inheritance. My mother was no more inclined than he to save. She was a true child of Italy-gay, improvident, and selfish. Heaven knows I heard that often enough from dear Grandmother-that, and how she rescued me from the depths of iniquity into which my mother had fallen."

"Iniquity?" breathed Ada.

I hesitated, but only for a moment.

"In Rome, the girls from the provinces dress in their native costumes and stand on the stairs near the Spanish Embassy to be hired out by artists. She was an artists' model when my father met her. After he died, she went back to her old life. Well, she had to have money, Ada. What else could she do?"

Ada was shocked into silence; her blue eyes were as wide as saucers. I was wicked to tell her, but not wicked enough to add that other bitter conjecture which my grandmother had hurled at me once, in the heat of anger-that I was not her son's child at all. A well-bred young English miss is not supposed to know about such things. But my grandmother had not spared me the knowledge. I thought of the stiffening form which lay below in the library, hands folded on its breast in unaccustomed humility. She was no colder, no less remote, than she had been in life. My voice was just as cold as I said:

"When Grandmother heard of this through her Rome agents, she sent them to my mother. My mother sold me to them-for fifty pounds sterling. She was living with a French officer at the time and she was delighted to have the money. Our grandmother told me of that tender maternal gesture quite often. She also reminded me frequently how, but for her generosity, I would now be a starving urchin in a dirty alley in Italy. Generosity! I would rather be left to the charity of strangers than endure such generosity. As," I added darkly, "I may yet be left."

Ada, poor child, is accustomed to my wild moods. She had been patting and soothing me as I stormed, but at that last remark she sat up and stared at me.

"Harriet, what do you mean?"

"Ada, has it never occurred to you to wonder what is to become of us? Does the future hold no apprehension for you?"

"Why, no. There is Grandmother's money. We will have that now."

"I suppose so," I said, without voicing my own suspicions on that point. "But how and where and with whom will we live?"

"I don't care," Ada said simply. "So long as I am with you. Oh, Harriet, promise me-we will never be separated, will we? You will always take care of me, just as you do now?"

I do have some shreds of conscience. I could not look at that candid child's face and infect her with my own pessimism or even vex her with the unaccustomed effort of thinking.

"Of course I will," I said gaily. "But the time will soon come, Ada, when you will prefer another sort of protector. Someone young and handsome, with moustaches like those of the young gentleman who turned to stare at you in the park last week!"

I sent her away laughing and blushing and protesting, but even her affection could not lighten my dark mood. Of course she will marry, and soon; she is so sweet-and will be so wealthy! Suitors will overwhelm her and she will take the first one to propose, simply to keep him from feeling unhappy.

I began to pace up and down the room, as is my habit when I am worried. The sunlight of early spring lay in a narrow strip across the matting beside my bed. The window shades were drawn, naturally, in deference to the rigid form that lay at rest in the library. Her death had been sudden. One moment she had been sitting upright in her chair scolding Hattie, the housemaid, for some fancied neglect of duty; the next moment her face turned a strange dusky red, her speech died into harsh gurgles, and she fell forward onto the floor.

There has been so little time. I cannot accustom myself to this new freedom; sitting in my room, I still expect the door to burst open, without the courtesy of a knock. I expect to hear a harsh voice demand why I am moping, with idle hands, in darkness. I need not hide my diary any longer! I am sure she found it, no matter where I hid it; very little escaped her prying fingers. Once or twice, after I had written an account of a particularly bad day, I fancied her little bright black eyes regarded me with more than their usual irony. Oddly enough, she never said anything. Perhaps, after all, I imagined those looks. . . .

Still, I feel more free now that those bright black eyes are closed forever. Although I said what I pleased about her in these pages, defying my own uneasy suspicions, I never dared voice my wilder fancies; I could not expose them to her mockery, her harsh chuckle. My diary has been a great blessing; it was the only outlet for my rages against Grandmother, for of course I never dared shout at her directly. She did not break my spirit, but she bent it rather badly.