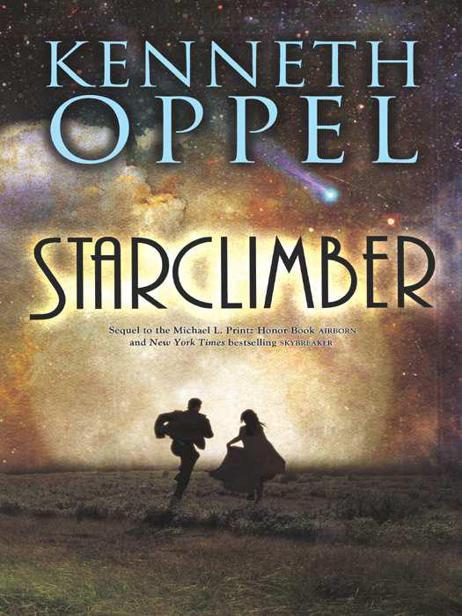

Starclimber

Authors: Kenneth Oppel

| Starclimber | |

| Matt Cruse [3] | |

| Kenneth Oppel | |

| HarperTeen (2010) | |

| Rating: | ★★★★☆ |

"Mr. Cruse, how high would you like to fly?"

A smile soared across my face.

"As high as I possibly can."

Pilot-in-training Matt Cruse and Kate de Vries, expert on high-altitude life-forms, are invited aboard the

Starclimber

, a vessel that literally climbs its way into the cosmos. Before they even set foot aboard the ship, catastrophe strikes:

Kate announces she is engaged—and not to Matt.

Despite this bombshell, Matt and Kate embark on their journey into space, but soon the ship is surrounded by strange and unsettling life-forms, and the crew is forced to combat devastating mechanical failure. For Matt, Kate, and the entire crew of the

Starclimber

, what began as an exciting race to the stars has now turned into a battle to save their lives.

Award-winning and bestselling author Kenneth Oppel brings us back to a rich world of flight and fantasy in this breathtaking new sequel to

Airborn

and

Skybreaker

.

Kenneth Oppel is the Governor General’s Award-winning author of the Airborn series and the Silverwing Saga, which has sold over a million copies worldwide. Kenneth Oppel lives in Toronto with his wife and their three children. Visit his website at KennethOppel.com.

For Philippa

1

The Celestial Tower

2

The Stars From Montmartre

3

A Little Schooling

4

Kepler’s Dream

5

Lionsgate City

6

The Garden Party

7

Training Begins

8

Underwater

9

Evelyn Karr

10

The Race Narrows

11

A Cycle in Stanley Park

12

The Final Trials

13

The First Astralnauts

14

The Astral Cable

15

The Starclimber

16

Liftoff

17

The End of the Sky

18

Raptures of the Heights

19

The Sky is Falling

20

Astral Fauna

21

A Message from Earth

22

The Counterweight

23

The Final Stretch

24

Etherians

25

A Reef in Space

26

Cut Loose

27

Reentry

28

Homeward Bound

R

ising into the wind, I flew, Paris spread before me.

For the first time in my life I was at the helm, though my ship was a humble one, and not my own. Aboard the

Atlas

we didn’t even use terms like “captain” or “first mate.” This was no fancy airship liner or private yacht; she was just an aerocrane, forty feet from stem to stern, but she was mine to command for the summer, and I loved every second of it.

“Elevators up five degrees, please,” I told Christophe, my copilot. “Throttle to one half.”

As the drone of the engines increased in pitch, I put the ship into a gentle starboard turn. We climbed, and I brought the

Atlas

about so that we faced the construction site. Though I had gazed upon it almost every day for two weeks now, the view still filled me with awe.

Rising three kilometers above the earth was the base of the Celestial Tower. Massive metal piers and arches supported its platforms, each one large enough to hold a city. The third platform had just been completed, and work on the next level was well under way, great spans of metal jutting skyward. Gliding over the site were dozens of aerotugs, delivering materials and prefabricated sections of piers to waiting work crews. From all across the tower came the flash of welders’ torches, fusing together girders. Already the tower was ten times higher than the Eiffel Tower, but it had much farther yet to go.

It was meant to reach all the way to outer space.

There was so much airship traffic around the construction site that it had its own harbor master. His voice crackled over our radio now, giving us our approach instructions. Hanging from the

Atlas

’s winch was a three-story-tall section of support pier to be delivered to the tower’s northern side. I turned the rudder wheel and brought us onto our proper bearing, circling the tower in a wide arc.

“Did you hear,” said Christophe, “that already they have named it the Eighth Wonder of the World?” Christophe was a Parisian, and extremely proud of the tower. He seemed to have an endless supply of information about it.

I nodded. “I saw it in the

Global Tribune

this morning.”

“How high you reckon they’re going to build this thing?” asked Andrew, coming forward from the cargo area, wiping his greasy hands with a rag. He was the winch operator, a hefty, red-faced fellow from Angleterre who’d moved to Paris, like so many others, to find work on the tower.

“I heard a hundred kilometers,” I said.

Christophe sucked his tongue in disagreement. “

Non, non, ce n’est pas vrai.

I heard at least a thousand.”

“Suits me,” said Andrew. “The higher they go, the longer I have a job. At these wages, I’ll be retired with me own castle before long.”

I too felt lucky. Piloting an aerotug for the summer would fund my final two terms at the Airship Academy. The French had hired tens of thousands of workers from all around the world. It was the greatest construction project in the history of mankind. The French boasted it made the Great Pyramids look like an afternoon garden project. Nothing, they said, would topple it. It was designed to sway, to bend with the elements, but it would never break. I hoped they were right, because if it ever did, it would fall over half of Europa.

“I thought it was meant to go all the way to the moon,” said Hassan, our Moroccan spotter, coming forward to peer out the windows of the control car.

“How could they do that, you numbskull?” said Andrew, whose tone was often a bit bullying. “The moon orbits around us, doesn’t it? We can’t go tying ourselves to it! We’d get all yanked about.”

Hassan nodded amiably. “Yes, I can see that would not be desirable.”

“At the summit of the Celestial Tower,” said Christophe with patriotic confidence, “they will launch a fleet of ships to travel into outer space, first to the moon and then beyond.”

This certainly seemed to be the government’s plan. All over Paris, buildings were plastered with posters,

PARIS TO THE MOON

! or

THE MARTIAN RIVIERA

! and showed chic ladies and gentlemen strolling through crystal lunar palaces or along red Martian beaches. Another poster proclaimed,

OUR BRAVE SPATIONAUTS

! and had a group of fit young men in silver suits, fists against their hips, staring arrogantly into the heavens.

“What I’d like to know,” said Andrew, “is where they’re finding these fellows daft enough to go into outer space.”

“They’ve set up some kind of special training facility, haven’t they?” I said.

“I have heard this also,” said Christophe wistfully.

“I think our Christophe here wants to be a

spationaut

.” Andrew sniggered.

“I am desolate I do not have the skills,” said Christophe, and he did manage to sound quite desolate when he said it.

“What about you, Matt?” Hassan asked. “If they asked, would you go?”

“In a heartbeat.”

“You’re a madman,” said Andrew. “Couldn’t drag me up there, not in a million years.”

“Of course, they will be selecting only Frenchmen”—Christophe sniffed—“so no need for you to worry.”

“The French are welcome to space,” said Andrew, “the entire black puddle of it.”

I didn’t share Andrew’s disdain. As cabin boy aboard the

Aurora

I’d spent lots of time in the crow’s nest staring at the stars. Their constellations blazed with myths and legends. I’d always wondered what it would be like to go farther, to get closer. At the Academy last term we’d studied celestial navigation, and now the night sky beckoned with even greater intensity.

But for now, space was for the French, just as Christophe said, and I’d have to be satisfied with helping them achieve their dreams. I didn’t feel too sorry for myself. My own dreams at the moment didn’t live in outer space anyway, but much closer to earth.

“We’re almost in position,” I told my crew. “Let’s get ready, please.”

Despite the fact I was the youngest aboard, the others never questioned my command, not even Christophe, who always gave the impression of knowing everything. My crew didn’t call me Captain or Sir or Mister, but I didn’t expect it. They knew I had authority over the ship, and I think they trusted me. We’d worked well together so far.

Andrew and Hassan went aft. The aerotug’s gondola was a single long cabin, taken up mostly by the cargo area, where the powerful winch was positioned above the open bay doors.

It was Andrew’s job to control the winch and Hassan’s to make sure we were positioned perfectly before lowering our cargo. From his caged spotter’s post on the underside of the gondola, Hassan had an excellent vantage point of what was directly below and gave me directions via speaking tube. His job might have sounded lowly, but it was vitally important.

“Level off, please,” I told Christophe, and throttled back, swinging us in toward the tower’s northern edge. I saw the waiting work crew below, the signaler guiding us in with his orange flags, and then we were almost overhead and Hassan was now the ship’s eyes.

“Slow ahead, slow, we’re almost at the mark,” came his voice through the tube.

I cut the engines back so we had just enough power to keep us dug in against the headwinds. Then I let Christophe take the throttle so I could concentrate on the rudder wheel for the final maneuvers.

“Nudge her to port,” said Hassan. “Too far. Bring her back a bit—you’re drifting astern…we’re on the mark!”

I heard the winch’s motor hum as it unspooled. It was always a tense time, lowering the cargo, because we had to keep the ship as steady as possible. Some days the crosswinds gave us a terrible shake.

“They’ve got hold of the guylines!” said Hassan. “We need another twenty feet, slowly.”

Andrew unspooled some more cable. I knew the workers would already be shunting the tower segment into place. Welding torches would flare to life, red-hot rivets would be swiftly hammered home. The tower had just grown another fifty feet.

“They’ve cast us loose,” Hassan said through the speaking tube. “Winch up!”

I put the throttle ahead a quarter and pulled us away from the tower. Behind us, the next aerotug was already waiting to deliver its load.

“That’s us done,” I said. We’d delivered our last load of the day, and our shift was over. I was looking forward to a break—and to seeing Kate this evening. I had a special surprise planned for her.

“What about this one?” Andrew asked from the cargo area.

I glanced back and saw a single wooden crate secured against the rear wall. I’d not noticed it until now.

“I thought we’d made all our deliveries,” I said to Christophe, reaching for the clipboard that held our manifest.

The sound of boots hitting the deck made me turn. A man had dropped down from the companion ladder that led up to the gas cells. In his hand was a pistol.

“Back against the wall!” he shouted at Andrew and at Hassan, who’d just climbed out of his spotter’s cage.

Two more men quickly dropped down from the ladder, guns clenched in their fists. All three wore construction coveralls. On their backs were bulky rucksacks.

Before I could radio a distress call, one of them, a pale fellow with a gaunt face, strode over and put a bullet through the transmitter. Then he leveled the gun at my head.

My first thought, absurdly, was: I’m going to be late for Kate.

“What the hell’s all this?” Andrew roared.

“Easy, everyone,” I cautioned. I didn’t know who these fellows were, or what they wanted, but it would do no good to anger them. Christophe seemed calm enough, though his cheeks were flushed. I was most worried about Andrew, for he had a brawler’s temperament, and I feared he might do something rash.

I doubted they were pirates, for we had nothing of value aboard. Maybe they were escaped convicts and needed speedy passage out of the country. They must have been aboard my ship the entire afternoon, waiting.

“We are going down to the southeast pier,” Christophe told me. “The first platform.”

I looked at him, confused, before realizing what was going on.

No one was pointing a gun at Christophe.

“You understand?” he said.

“What’s going on?” I demanded.

“We fly normally. Do not try to attract attention. We shall begin now.”

He was keeping me at the helm, which meant he didn’t know how to fly the ship alone. I took the rudder wheel and eased the throttle forward. “Elevators down three degrees.”

I would not say please anymore. My heart beat wildly, and I was glad I had my flying to keep my panic in check. The back of my head throbbed, as if the pistol projected deadly heat.

“Why’re we going down there?” I asked.

He ignored me.

“Christophe, you great gaseous frog!” Andrew roared. “What d’you think you’re doin’?”

“Shut your pie hole or we’ll gag you!” one of the other men said.

I guided the

Atlas

down toward the first platform, watching carefully for other airships. Our flight was unauthorized, and right now the harbor master would be trying to raise us on the radio. Frightened as I was, it irked me, knowing the harbor master and other pilots would be thinking me an incompetent menace.

The southeast pier was one of the four cornerstones of the tower, a massive fortress of interlocking girders that supported not only the first platform but all above it. We were approaching it from the south at a thousand meters. I throttled back, not wishing to draw too close. I had no idea what Christophe’s intentions were.

“Level us off,” I told him.

“No. We will go underneath the platform.”

“Underneath?”

“Correct. Inside the pier.” He pointed through the window at the close weave of girders. “There.”

“I’m not sure there’s room,” I said.

“There is room,” he said with complete assurance.

“You’ve studied this, have you?”

“A very great deal,” he said.

We were headed straight for an opening that looked no larger than the

Atlas

. A cross gust shook us off course, and we both struggled with elevators and rudder to keep us on target, for there was little margin for error. Into the pier we went, nearly grazing the underside of the platform. Stray ten feet to either side and our engines would be sheared straight off. We glided deeper inside.

Christophe reached for the throttle and killed the engines. “Tie up the ship,” he shouted back at his men.

The gaunt fellow who’d had his pistol trained on me strode aft to help.

“Your work is done,” Christophe said to me, pulling a pistol from inside his jacket and grabbing my arm. He marched me into the cargo area, where his men had thrown open the gondola’s side hatches. They held grappling lines and let fly. The hooks swiftly caught hold amidst the girders, anchoring the

Atlas

.

I looked down through the open bay doors and saw the ground through a crisscross of girders, a thousand meters below.

“You two!” shouted the gaunt fellow at Andrew and Hassan. “Bring the crate over here.”

Glaring hatefully at the hijackers, Andrew slowly walked over to the crate with Hassan. The two of them released the straps and pushed it across the deck toward Christophe.

“That’s far enough,” he told them, when it was within ten feet of the bay doors. “Back against the wall. You also,” he said, giving me a shove.

“I never liked him,” Andrew growled to me. “Always so full of himself.”

I looked over at Hassan, who was very quiet, but I saw his hands shaking.

“Open it, Pierre,” Christophe said to the gaunt man.

The fellow obediently holstered his gun and pushed back the crate’s lid. Inside was enough dynamite to knock the face off the moon. I felt sick, thinking this had been aboard my ship all day without my knowing. A complicated tangle of fusing sprouted from the dynamite and fed into an archaic device that looked half steam engine, half grandfather clock. The clock face had two hands, both pointing at twelve o’clock, and underneath a large winding key.