Stonehenge a New Understanding (26 page)

Read Stonehenge a New Understanding Online

Authors: Mike Parker Pearson

Tags: #Social Science, #Archaeology

This double arc was thought by Atkinson to be the partial remains of two concentric circles of bluestones. He called the outer arc the Q Holes and the inner arc the R Holes. Atkinson’s excavations in 1954 had found

that one of the stoneholes in the sarsen circle (Stone 3) cut into the edge of one of the Q Holes (Q Hole 4). Wherever one pit cuts another, we know that the second pit is later than the first. What Atkinson found meant that the Q and R Holes had to be earlier than the sarsen circle. Atkinson had excavated some twenty Q and R Holes but found nothing that could be used to radiocarbon-date their construction. Geoff and Tim hoped they would be luckier.

The Stonehenge Riverside Project made the second of that year’s applications. I had invited Julian Richards and Mike Pitts to join us. Julian’s Stonehenge Environs Project had made a major contribution to understanding Stonehenge,

3

and he was hugely enthusiastic about the opportunity to dig at Stonehenge itself. Mike also has a considerable amount of knowledge about Stonehenge, having dug there—outside the wire—in 1980 in advance of the cable trench.

4

We wanted to recover a large quantity of cremated human bones dug up by Hawley in the 1920s. These cremated remains were found primarily in the pits known as Aubrey Holes; this circle of fifty-six pits lies inside the Stonehenge ditch and dates to the first phase of activity at Stonehenge. In 1935 these remains had been reburied, for safe keeping, in Aubrey Hole 7 by archaeologists Robert Newall and William Young. It seems that they could find no museum prepared to take the cremated bones, probably because back then, long before the development of today’s methods and techniques of analysis, there appeared to be no possibility of ever learning anything from them.

5

The committee members of EHAC must have had a difficult decision to make: Should they refuse both applications, on the grounds that Stonehenge’s below-ground remains should never be disturbed, or grant permission to just one project, or agree to both? Fortunately the committee was happy to see both proposals go forward. Each project had a long and fruitful track record over the previous five years, Tim and Geoff in the Preselis and ourselves around Stonehenge. The excavations were supported by meticulous research designs, and would have little impact on preserved remains because of the small sizes of the proposed trenches. Plus, these quite tiny trenches would be placed in or adjacent to areas already dug by earlier archaeologists.

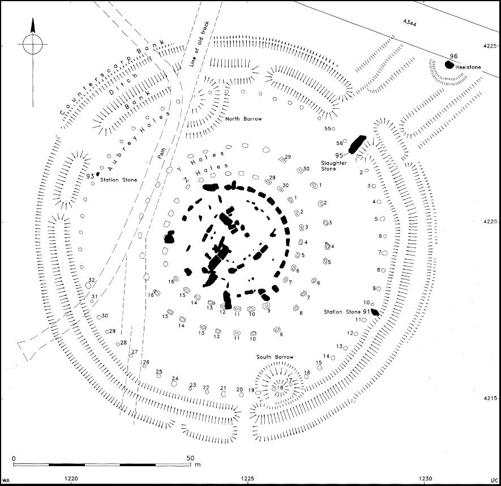

Tim and Geoff planned to re-open one of Atkinson’s trenches, between the sarsen circle and the trilithons, and then extend for

about two meters into untouched deposits. The trench was positioned in the southeast area of the monument (between Stones 10 and 35; see figure on

page 29

), on top of the line of Q Holes, immediately outside the stones of the bluestone circle.

6

Atkinson had recorded half of a Q Hole in the end of his trench here; Tim and Geoff would be able to dig out its other half, and they hoped to find another Q Hole to its west.

7

This end of Atkinson’s trench had been full of postholes, so there was a good chance that they might find more of these and be able to date them.

A plan of Stonehenge showing the locations of the excavated cremation burials (black circles) in the Aubrey Holes and ditch.

By 1956, Atkinson had mapped out the extent of the Q and R Holes in the northeast and east areas of Stonehenge.

8

He must surely have looked very hard for a similar double arc of stoneholes on the west and southwest sides, but there is only a single arc in this area. The Q and R Holes, and their place in the story of Stonehenge, can be difficult to follow, particularly because these are stone

holes

, not stones. Briefly, the Q and R Holes are where bluestones once stood. The bluestones were pulled out of these holes around 2400 BC and then reerected, in much the same arrangement, as a bluestone circle. The Q and R Holes are mostly underneath where the bluestone circle stands today; nobody knows why the prehistoric builders went to the trouble of removing and then re-erecting these stones.

Some archaeologists think that the rings of Q and R Holes were never finished. Others think that an incomplete double arc was all that was intended. Another possibility, which seems to me more likely, is that as far as the builders were concerned the arrangement

was

complete, given the symmetry in the arrangement of bluestones in a double arc on the northeast side and single stones on the southwest side.

Atkinson’s other major discovery was that Q Hole 4 appeared to be cut by the stonehole containing one of the stones of the sarsen circle (Stone 3).

9

Thus the Q and R Holes were thought to be earlier than the sarsen circle, and probably earlier than the sarsen trilithons. Atkinson appeared to have discovered a separate phase of construction at Stonehenge, between the earliest phase of bank and ditch and the sarsen circle. The arrangement of small bluestones belonging to this phase was itself later modified by the erection of the sarsens and the re-arrangement of the bluestones into a bluestone circle and bluestone oval at the center of the monument. If the Q and R Holes were the first bluestone construction at Stonehenge, then if Tim and Geoff could find dating evidence in one of the Q Holes this would, they reckoned, reveal when the bluestones were brought from Wales.

Their dig started in March 2008, with cameramen jostling to film Tim and Geoff cutting the first sods. There were daily updates on the web, a live feed to a screen in a tent in the visitors’ parking lot, a blog, and web forums. Mike Pitts, Julian Richards, and I visited them after their first week’s digging. Tim told us that he had spotted that the cuts of the

features in the end of Atkinson’s trench were not doing what they should have done. He could see that the Q Hole actually cut the hole for the fallen stone of the sarsen circle. According to Atkinson, the relationship between these two pits should have been the other way around. We were all mystified.

Tim and Geoff were unlucky: There was no antler pick in the Q Hole. Given that more than twenty Q and R Holes had already been dug out by Hawley and Atkinson without a sniff of one, it had always been a long shot; it seems it just wasn’t Neolithic practice to leave picks in these particular pits. The situation was, however, salvageable. Geoff and Tim hoped to collect enough pieces of charcoal and bone to be able to radiocarbon date groups of such items from particular layers. By the end of the excavation, their hard-working flotation team had accumulated a modest collection of charcoal lumps, along with a few pieces of animal bone and a human tooth.

There was a lot of pottery, too. Atkinson’s excavation team hadn’t sieved the soil and had missed some sizeable shards of Beaker pottery. What really surprised Tim and Geoff, though, was the quantity of Roman pottery. Just like the Cuckoo Stone, this place had been a magnet for people in the Roman period. They didn’t come just to look at the standing stones, but actually dug holes into the site. Even deep in the Q Hole, Geoff and Tim found a shard of Roman pottery. It was no wonder that the stratigraphy was mixed up, as we’d seen on our site visit. These holes had been dug into and refilled long after they were first used in the third millennium BC.

By the end of the environmental processing, Tim and Geoff had enough pieces of charcoal to submit several samples from each context. These came from a sarsen circle stonehole (Stone 10), from two stoneholes belonging to the bluestone circle, and from a Q Hole. Cut by the Q Hole, and therefore earlier than it, were two small postholes. Only one had a piece of charcoal in it. This was the first opportunity in many years to look carefully at postholes in Stonehenge. Like the others found by Hawley and Atkinson, these two were less than half a meter across. Curiously, they had no post pipes and no packing, nor was there any indication that posts had been withdrawn. Their fills were utterly homogeneous. Tim even wondered whether they had really held posts.

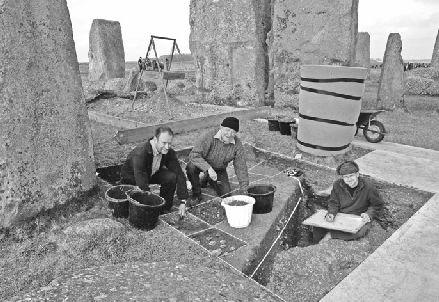

Tim Darvill (left), Geoff Wainwright (center), and Miles Russell (right) excavating at Stonehenge in 2008.

After a cold few weeks of gray skies and rain (and some unseasonable snow), Tim and Geoff finished off and filled in their trench. They would now have to wait months for the results of the radiocarbon dating. Mike Allen was advising them on this and, well aware of the amount of previous disturbance, set out a strategy to follow:

- First of all, identify the tree species from which the charcoal came, and then select only those pieces that derived from small roundwood. Dating charcoal formed from heartwood is not much use; if a heartwood sample happens to have come from a large tree, it will have already been centuries old when it was burned. Such a date only tells us how old the tree was, not the date of the event at which it was burned.

- Then submit the roundwood samples for dating.

- The dates from such a strategy can only be considered reliable if pairs of dates from the same context are consistent with each other. If inconsistent, then the layers have been mixed up at a later date.

- In addition, the dates must be consistent with the stratigraphy: Earlier dates should come from layers lower down in the stratigraphic sequence, and later dates should come from the upper layers.

- If the dates were to come out all over the place—completely different dates from the same layer, say, or much older dates from layers above much younger dates—then none of the stoneholes and postholes could be considered as securely dated.

In August 2008 came our turn. We’d be digging Aubrey Hole 7 to recover Hawley’s finds of cremated bones. Because Tim and Geoff had gone first, digging at Stonehenge was no longer big news so we were spared the press onslaught. Nevertheless, there were going to be thousands of visitors at Stonehenge every day in August, so part of our project design concerned visitor management. We needed a good team to explain to the visitors why we were digging, and what we hoped to find. Pat Shelley, a professional Stonehenge guide who had worked with us at Durrington Walls, ran a small army of trained students and National Trust volunteers from a tent outside the parking lot, giving guided tours of accessible excavations in a nearby field as well as dealing with visitors gathering inside the monument near the excavation site.

As we set up, we noticed a white-robed figure displaying a banner on the fence outside the visitors’ entrance to Stonehenge: a Druid, protesting against the Stonehenge entry charge. His banner proclaimed that the site should be open to all, free of charge; the fences should all come down and people should be allowed to walk among the stones whenever they like. It’s a nice idea. When I saw Stonehenge as a child, everyone could wander about at will and it was definitely a better experience. Many people find Avebury henge a much more interesting and atmospheric place than Stonehenge, partly because it has unrestricted access, but we have to remember that Avebury is much bigger than Stonehenge and not on the tourist track in the same way.

Whatever we may think about access to Stonehenge, it now attracts almost a million visitors a year, and that’s a problem in terms of its preservation. English Heritage has decided that the best way to protect the site from erosion is to keep visitors to a fixed path that runs outside the

sarsen circle. Anyone wanting to see the stones up close can get inside the circle only as a visitor with a reservation and outside normal opening hours. The two exceptions are the solstices, when anyone and everyone is allowed in. Currently about 37,000 turn up for the midsummer solstice; the midwinter solstice is still very much for the hard core, and usually only a couple of hundred people brave the winter weather for a night in the open. English Heritage and the National Trust have to take responsibility for all the arrangements for the solstices (for which no charge is made): They install portable johns, arrange the parking, campsites, and first-aid facilities, and pick up all the garbage.

The Stonehenge manager had been in touch with his Druid contacts to tell them what we’d be doing. Many different people today call themselves Druids, from members of Friendly Societies established before the twentieth century to twenty-first-century Pagans. The Stonehenge management team has a tough job: It must not just protect the monument, and provide a fulfilling and informative experience for visitors, but also try to stay in touch with the many different interest groups. Our plan being to retrieve human bones from Stonehenge, I could see that some people would find a new grievance to campaign against. Sure enough, it wasn’t long before a new placard appeared near the ticket office: “We the loyal Arthurian warbands and our orders, covens, and groves, and the Council of British Druid Orders oppose the removal of our ancient guardians: Aubrey Hole seven.” It was going to be an interesting week.