Stonehenge a New Understanding (51 page)

Read Stonehenge a New Understanding Online

Authors: Mike Parker Pearson

Tags: #Social Science, #Archaeology

In spite of Renfrew’s impeccable refutation of the Mycenae theory, we do still have to ask whether some distant civilization, flourishing at an earlier date, could have influenced the building of Stonehenge. It seems that many people are intrigued by the possibility of a link between Stonehenge and some other culture, being apparently reluctant to

accept that a group of Stone Age British farmers could have come up with either the idea or the engineering skills without outside help. We therefore need to look at ancient Egypt (although I’m not going to waste any space discussing the “built by aliens” nonsense).

The first of the three great pyramids of Giza, the pyramid of Khufu or Cheops, was built during the first half of the twenty-sixth century BC.

38

It would have been a brand-new, state-of-the-art structure when the sarsens went up at Stonehenge, probably at the end of that century. Each pyramid at Giza had an associated mortuary temple that was connected by a causeway to a valley temple beside the Nile. Although Stonehenge has nothing in common with the form of the Giza pyramids’ construction, it does have a vague similarity to the architecture of the valley temple of Khafra (or Chephren), who reigned in the second half of the twenty-sixth century BC and built the second Giza pyramid. Although Khufu’s valley temple can no longer be seen, Khafra’s has a rectangular arrangement of pillars and lintels.

The arrangement of valley temple, linking causeway, and mortuary temple (placed next to the pyramid) also strikes a faint chord with the relationship between Bluestonehenge, the avenue, and Stonehenge. Unfortunately for the enthusiasts for foreign-intervention arguments, this slight similarity is entirely fortuitous. Construction at Stonehenge started long before the great pyramids were built, and the juxtaposition of Stonehenge and Bluestonehenge is probably many centuries earlier than Khufu’s pyramid and valley temple. To claim any direct link is pushing interpretation of similarities much too far, especially in the total absence of any other evidence for contact between Britain and ancient Egypt at that date.

The Amesbury Archer’s long-distance movement does, however, prove that some individuals traveled more than 400 miles in a lifetime. We cannot rule out the possibility of garbled stories about distant splendors passing from ear to ear over a distance of 2000 miles or more and over many lifetimes. Yet we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that Stonehenge and the contemporary wooden circles at Durrington Walls were built in geometrical styles whose ancestry was definitely British. There never were any Egyptian or Mediterranean missionaries, architects, or builders.

Ultimately, we don’t need to look for the source of the ideas behind Stonehenge by going any further than Britain. Putting really big stones on top of each other had long been practiced, since the fourth millennium. All around western Britain, the simple megalithic structures called portal dolmens were built hundreds of years before Stonehenge, around 3800 BC and after. In the case of Pentre Ifan in Preseli, the capstone, perched on three uprights, weighs around 16 tons.

39

Closer to Stonehenge, the long barrow of West Kennet near Avebury contains a stone chamber, built around 3650 BC, whose entrance consists of a large slab supported by upright sarsens.

40

Although access to West Kennet was blocked off around 2400 BC, constructions like these were visitable ancient monuments for Stonehenge’s designers around 2500 BC.

It is possible that these old tombs provided food for thought for the Stonehenge builders. The only problem is that, having been built more than a thousand years earlier, their style would have been rather “retro.” There might have been another, more current source of architectural ideas, albeit in another material. Josh has sometimes said that Stonehenge is our most impressive example of a timber circle. What he means by this curious (and at first glance contradictory) statement is that Stonehenge was built to look as if it were made of wood. The stonemasons used the techniques of wood-working, as archaeologists have known for decades. The dressing of the faces of the stones, the mortise-and-tenon joints, and the tongue-and-groove jointing of the lintels all derive from carpentry.

Neolithic builders would have been completely familiar with the appearance and construction of house doorways, in which a horizontal lintel rests on two upright jambs. In addition, they probably used lintels in monumental wooden architecture. Over the previous century or three, Neolithic people had been building timber circles throughout Britain and Ireland with regularly spaced uprights whose tops could have been spanned by wooden lintels.

41

We cannot prove that lintels were added to these timber circles, since we only ever see where the bases of the posts stood, but it seems more likely than not. Stonehenge was something of a

trompe l’oeil

, a timber circle made of stone.

The interiors of many timber circles had central posts arranged in a square. The Northern Circle and the Southern Circle at Durrington

Walls are both good examples of this use of a square within a circle. The structure inside Coneybury henge is probably another, earlier example.

42

This format of a circle with an interior square arrangement can be found as far away as Ireland, where similar post circles are known at Ballynahatty near Belfast, and at Knowth on the Bend in the Boyne near Dublin.

43

Josh has also spotted that the houses at Durrington Walls have the opposite arrangement—a circle within a square. In domestic architecture, a circular hearth pit was set within a square-walled house with rounded corners. The two houses excavated by Julian Thomas within the western half of Durrington Walls are a variation on a theme. These had four interior postholes forming a square around the circular central hearth, as well as being enclosed within square walls. Both houses were enclosed by circular palisades.

Does this juxtaposition of circles and squares provide a clue for understanding why there was a horseshoe-shaped setting of five trilithons within the center of Stonehenge? It is possible that the four shorter trilithons are a representation of the corners of a stylized house, in which the great trilithon is the doorway. The problem with this idea is that the trilithons’ horseshoe arrangement is more of a curve than a square. We might also expect corners to be marked by single uprights rather than pairs.

Of course, not all houses were square in plan. The largest ones in southern Britain, around 12 to 13 meters by 11 meters, had D-shaped or horseshoe-shaped plans. Ephemeral traces of one of these D-shaped structures were found next to the Southern Circle at Durrington Walls in 1967, although at the time of excavation it was thought to be just a hollowed-out midden, or garbage heap. Another is located just inside the south entrance through the ditch at Stonehenge, and was later covered by the South Barrow. Stonehenge’s North Barrow may hide a third example. With no obvious hearth, these may have been public buildings or meeting houses.

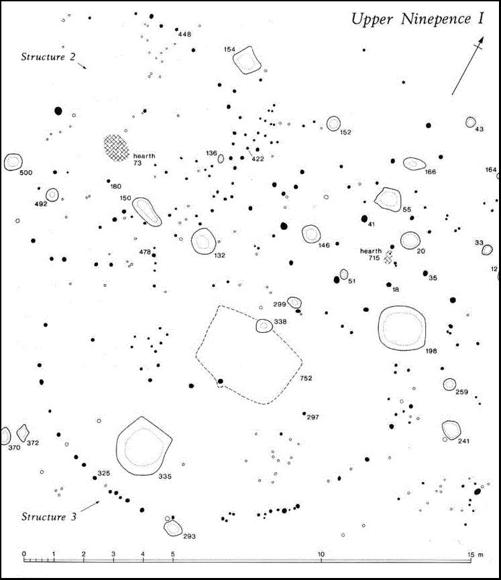

Such D-shaped houses are known from one other location in Britain, from the charmingly named village of Upper Ninepence in Powys, Wales.

44

In 1994, archaeologist Alex Gibson was excavating a Bronze Age barrow near the village and discovered Neolithic remains preserved underneath this burial mound. Among the various pits were three

semicircular settings of stakeholes. Alex was sure these had to be the remains of circular houses but there were no traces of stakeholes to form full circles despite the excellent preservation of the ground surface beneath the barrow. In hindsight, these structures can be interpreted as D-shaped houses. The two smaller ones had hearths but the largest, at 12 meters by 9 meters, had no fireplace. Radiocarbon dates put their construction in the period 2900–2500 BC, probably slightly earlier than the Durrington Walls D-shaped house.

The plan of the Durrington Walls D-shaped house, located next to the Southern Circle, can fit snugly within a horseshoe setting of ten large posts at the center of the Southern Circle’s second phase. Given that the D-shaped house probably belongs with the circle’s first phase, it could have been the model for this horseshoe setting. This horseshoe of posts replaced an earlier square of posts at the center of the circle. Thus, the horseshoe setting in the Southern Circle may represent in monumental form the D-shaped meeting house, a new architectural design to replace the traditional format of a square of posts that represented the rectangular domestic house. This would also explain the shape and size of the trilithon setting at Stonehenge, or at least its southwestern arc formed by the great trilithon and its two neighboring trilithons. Yet there is an additional form in which the D-shaped meeting house was represented monumentally.

Turning to Woodhenge, the arrangement here of six concentric rings of posts has conventionally been perceived as an oval. Even allowing for minor inaccuracies in excavator Maud Cunnington’s plan, it is better understood as a pair of concentric semicircles of posts facing each other across the middle of the monument. Look carefully at the plan in Chapter 5 and it is apparent that the two half-circles do not meet precisely along the structure’s northwest-southeast axis. The builders of the two halves also positioned the ramps of the largest post circle in two different ways. In the northeast D-shape, the posts were erected from ramps inside the semicircle. The southeast D-shape is distinctly different, because the posts were erected from outside the semicircle. Perhaps Woodhenge represents the joining of two monumental representations of the D-shaped house.

On this plan of the pits and stakeholes excavated by Alex Gibson at Upper Ninepence in Wales, one can trace the outlines of two D-shaped buildings. The larger (Structure 3) appears to have had no hearth; the smaller (Structure 2) does.

Such a “double D” form is also found in the bluestone oval at the center of Stonehenge. Although it, too, has been considered as an oval, it may in fact be formed of two semicircles. The clue to this is the position of one particular bluestone (Stone 61a), now reduced to a stump.

It is off the line of a proper oval (which may explain why it is even sometimes left off plans of the bluestone oval) and lies at the intersection of the two semicircles formed by the two halves of the oval.

We may conclude that Stonehenge incorporates constructional principles also found in the Southern Circle—the horseshoe plan of uprights—and from Woodhenge—the double D plan. Since the Southern Circle was laid out using long feet, and Woodhenge was laid out in short feet, this could explain why both units of measurement were employed at Stonehenge. In summary, Stonehenge amalgamates architectural elements of both timber circles. At its center is a stone representation of a meeting house—the meeting place of the ancestors of the people of Britain.

If the plan of the trilithons can be explained in this way, how do we account for their lintels and for there being five of them? They have long been considered as representations of doorways, but we have no idea where the doorways were on the D-shaped meeting houses. People have wondered if the trilithons represented doors to another world, but they could equally have symbolized five tribal lineages charting their descent from five original households or founding ancestors. In this respect, it is interesting that there are five house enclosures in the interior of Durrington Walls, forming an approximate arc facing down the valley toward midwinter sunrise. Could these be five tribal or clan houses, with the largest of them in the center represented at Stonehenge by the great trilithon? Unfortunately, the otherwise neat arc of enclosures is not perfect, as the southernmost enclosure is about 100 meters off the line of the arc.

The Stonehenge of 2500 BC is an amalgam not just of features referencing the timber circles of Woodhenge and the Southern Circle, but also of two types of stone already present on the site. At this time, the shaped sarsens were brought to Stonehenge, dressed and arranged so that they enclosed the re-arranged bluestones (formerly in the Aubrey Holes). The stones with Welsh origins were now contained within arrangements of stones brought mostly from the Marlborough Downs. This raises the possibility that Stonehenge’s identity, as expressed through the stones’ origins, represented a union of two groups with geographically diverse ancestries—the people of the bluestones and the people of the sarsens.

One of the problems with which we’ve been wrestling at Durrington Walls is why there were two wooden versions of Stonehenge—the Southern Circle and Woodhenge—and why Woodhenge was placed in a location marginal to the Southern Circle and its avenue. We did think that the two timber circles might have been built and used at different times, with Woodhenge replacing the Southern Circle, but the dates of the two structures suggest that this is not a good explanation. Although Woodhenge’s henge ditch was not dug until 2400–2280 BC, the person whose cremated bones were buried in hole C14 of Woodhenge died around the same time as the Southern Circle was constructed, more than a century earlier.