Stonehenge a New Understanding (6 page)

Read Stonehenge a New Understanding Online

Authors: Mike Parker Pearson

Tags: #Social Science, #Archaeology

Barrow-digging went on all over Britain, a cross between a gentleman’s hobby, a sport, and serious research. In 1802 a famous barrow digger called William Cunnington dug a pit two meters deep by the Altar Stone, close to Stukeley’s trench.

7

Halfway down he found Roman pottery but close to the bottom there were pieces of charred wood, prehistoric pottery, and pickaxes made from red-deer antlers. Without realizing, Cunnington too had blundered into the mysterious prehistoric pit in the middle of Stonehenge. In 1803 and 1810 he dug against the recumbent Slaughter Stone, establishing that it had originally stood upright.

In 1839 a naval officer, Captain Beamish, dug out an estimated 114 cubic meters (400 cubic feet) of soil from the front (northeast) of the

Altar Stone, much of which was probably chalk bedrock.

8

Captain Beamish’s big hole was probably the final blow for any prehistoric features—pits, postholes, stoneholes, or ephemeral hearths—that once lay at Stonehenge’s center. Whatever was there was almost certainly utterly destroyed by these early investigations.

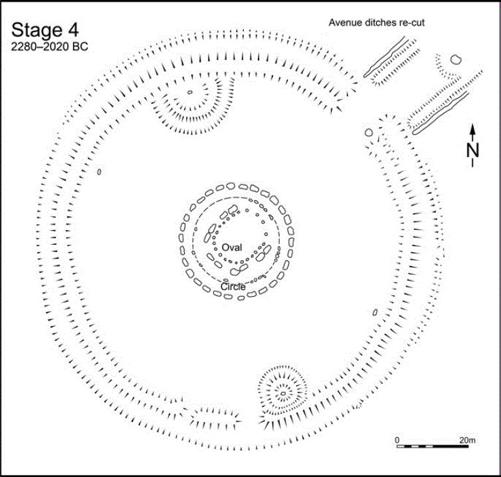

Plan of Stonehenge Stage 4 (2280–2020 BCE), showing the bluestone oval and circle.

The famous Egyptologist Sir William Flinders Petrie began his archaeological career with a survey of the stones between 1874 and 1877; he was keen to produce something accurate to improve on the plans produced by earlier antiquarians John Wood and Sir Richard Colt Hoare. Petrie’s main legacy was a numbering system for the sarsens and bluestones that archaeologists still use today.

9

Petrie was a

great archaeologist; he never dug at Stonehenge but was nevertheless the first to work out that the henge ditch and bank were constructed before the sarsen circle and trilithons. He also pointed out that the sarsen circle, with its ring of horizontal lintels resting on the upright stones, had possibly never been finished, because one of its stones (Stone 11) is too short—perhaps the builders couldn’t get enough large sarsens to finish the circle.

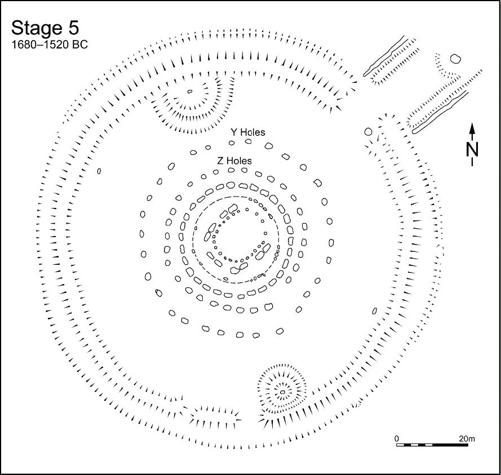

Plan of Stonehenge Stage 5 (1680–1520 BCE), showing the Y & Z Holes.

In 1877, Charles Darwin took his family on a picnic to Stonehenge.

10

He and the children dug two small holes, one against the fallen upright of the great trilithon and the other against another fallen sarsen, not to look for finds but to investigate the power of earthworms to move huge

stones. Darwin had realized that earthworms not only convert organic material into soil, but also sort the soil so that even large stones, as well as small components, are moved vertically downward. When we look at a soil profile that has not been disturbed by plowing for many centuries, we can see the effects of worm-sorting because the stones and pebbles lie at the bottom, beneath a layer of fine earth. In 1881, Darwin published his findings in his other great book,

The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms, with observations on their habits

. Although he was not particularly interested in archaeology, Darwin’s work on earthworms still has relevance for anyone excavating at Stonehenge today.

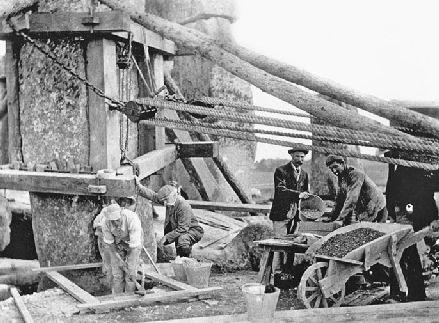

The first director of excavations at Stonehenge in the twentieth century was William Gowland, a professor in his sixties, who dug around the base of the surviving upright of the great trilithon (Stone 56).

11

He did this as part of an exercise to re-set the sarsen monolith, which was leaning heavily and likely to fall down. Although a mining engineer, chemist, and metallurgist by training, Gowland had a background of amateur archaeological research in Japan, where he had excavated more than four hundred ancient tombs. The work on the great trilithon was carried out in 1901, and the results published promptly and in great detail the next year. Though his trench was only small, Gowland found more than a hundred artifacts—mostly worked flints and sarsen hammerstones. His recording was meticulous—sections

g

were drawn of the stone sitting in its stonehole, a plan was made of the trench, and the major finds were plotted in three dimensions. He could have had little idea that his records would be essential for working out the chronology of Stonehenge over a hundred years later.

In 1918, Stonehenge was given to the nation.

12

The Office of Works realized that more stones were leaning dangerously and that there would

have to be a modest program of restoration. Gowland was too old to carry out the excavations that the repairs would necessitate, so the job was given to Lieutenant-Colonel William Hawley. Petrie had wanted to excavate Stonehenge himself—with this in mind, he had even intended to buy it from its last private owner, Cecil Chubb—but Hawley was director of the Society of Antiquaries, the archaeological body advising the Office of Works, and got the job. Over the next eight years Hawley excavated not just the holes of the stones to be restored but almost half of the entire monument.

13

Many archaeologists have since bemoaned this twist of fate. Petrie was the greatest archaeological excavator of his age, whereas Hawley’s abilities were later described as regrettably inadequate.

14

Professor William Gowland (kneeling center) supervising excavations at Stonehenge in 1901.

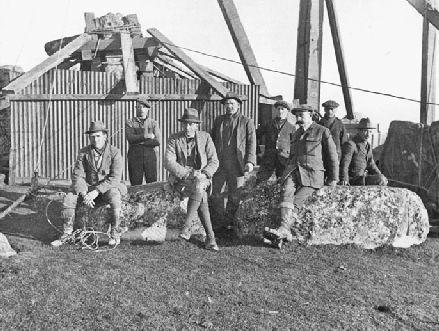

Hawley had served in the British army and was a keen amateur archaeologist who had dug at Old Sarum (the old medieval town of Salisbury, nestled within the ramparts of an Iron Age hillfort). Already widowed, Lieutenant-Colonel Hawley was sixty-nine when he started work on Stonehenge in 1919.

Apart from during the stone repairs, which were carried out by workmen employed by the Office of Works, Hawley mostly worked alone over long annual seasons, between spring snowstorms and autumnal gales, occasionally helped by Robert Newall, a local enthusiast. Most days he walked the five miles from his lodgings in the old mill at Figheldean, and occasionally lived on site at Stonehenge in an Office of Works hut.

He and his team dug trenches in various areas, from Stonehenge’s external ditch to the central settings of sarsens and bluestones. Across much of the interior he found nothing but bare chalk. However, the ditch that encircles the stones was full of Neolithic deposits. Inside this ditch there was once a bank of soil standing two meters high (now less than a meter high). Just inside the bank, Hawley found a circle of fifty-six pits, known as the Aubrey Holes. These are named after the antiquarian John Aubrey.

Hawley excavated thirty-two of these Aubrey Holes, digging out the soil and artifacts that filled them. In both the surrounding ditch and in this circle of pits he found lots of cremation burials—small heaps of burned human bones that, he surmised, had been deposited in long-since rotted leather bags. Hawley dug every year at Stonehenge from 1919 to 1926 (by which time he was seventy-six years old). His methods were thorough and he recorded his observations daily in a notebook. At the end of each season he delivered a lecture on his findings to the Society of Antiquaries, which published it in its annual journal. Although Hawley lived to a ripe old age (into his nineties), he never published an overall account of his work; today Salisbury Museum takes care of his notebooks.

Lieutenant-Colonel William Hawley (seated right) with his team of workmen at Stonehenge in 1919.

There’s no doubt that Gowland and Petrie were better excavators: Hawley failed to draw many of the plans or sections that we would expect from modern excavations, and his section drawings in particular are often too schematic to be of much use. And not only did he fail to publish a book on his discoveries but also he seemed never to develop any working hypotheses or research questions to test in his excavations. At the end of his work he admitted to being at just as much of a loss about the purpose of Stonehenge as he’d been when he began.

15

In some ways, however, Hawley has had bad press. We know what he found and roughly where he found it. Between his diary and his interim reports, there’s enough to be able to re-explore and re-interpret some of the more tangled problems created by his digging. There are some very detailed accounts in the fillings in the Aubrey Holes and the Stonehenge ditch, for example. Working through his reports has proved to be an exciting armchair excavation, almost as much fun as carrying out the excavation itself, discovering important clues that have been missed by previous researchers.

After the Second World War, a group of three archaeologists—Atkinson, Piggott and Stone—agreed with the Society of Antiquaries that they should write a full report on Stonehenge and carry out some limited excavations to resolve some of the problems thrown up by Hawley’s work. In 1950 they began with two Aubrey Holes. By 1964 their “limited program of fresh excavations” had turned into more than forty trenches within Stonehenge and its avenue.

16

(Professor Richard Atkinson returned

in 1978 for a final season with a Cardiff colleague, environmental archaeologist John Evans, and Alexander Thom.

When he began working at Stonehenge, Atkinson was a young and dynamic lecturer at the newly created archaeology department of Cardiff University, and his methods were revolutionary, using skilled archaeologists working with trowels and making careful observations of soil and stratigraphy. Even as late as the 1950s the actual digging in archaeology was usually left to unskilled laborers; in his textbook on field archaeology, Atkinson not only outlined a better way of going about things but he also put it into practice.

17

From his first dig of two Aubrey Holes in 1950 to his last excavation (of the circular ditch in 1978), he brought into common use new methods and skills.

Atkinson was helped in the Stonehenge excavations by Stuart Piggott, professor of archaeology at Edinburgh University, and by J. F. S. ‘Marcus’ Stone, an amateur archaeologist who worked nearby as a scientist at Porton Down, the Ministry of Defence research center. Atkinson published his team’s Stonehenge excavation results in 1956, and in 1979 he added a few pages to a new edition of this important book on Stonehenge, but he never published the full details of his findings, so it has been hard for others to evaluate his work and results.

18

Paradoxically, he criticized Hawley’s work for the same reasons: “A regrettable inadequacy in his methods of recording his finds and observations and, one suspects, an insufficient appreciation of the destruction of archaeological excavation per se, has left for subsequent excavators a most lamentable legacy of doubt and frustration.”

19

Unlike Hawley, Richard Atkinson seems not to have written much at all in the way of field notes.