Strange Embrace (19 page)

Authors: Lawrence Block

“Lennie? Yeah, I thought he’d call. He wants me to give him a job. I’ll have to find something for him to do.”

“He doesn’t want a job.”

“You sure?”

Ito nodded positively. “Matter of fact, he wanted to make an appointment with you. A business appointment.”

“Of course. You see, I told him I’d get him some sort of job in the theater. The production end of things. Something to do so he can learn the business—”

But Ito was shaking his head. “He said to tell you that he read the story in the newspapers. He said that the theater seems a little too risky. ‘A cat only lives once, he might as well live as long as he can.’ I think those were the words he used.”

“Then,” Johnny asked, puzzled, “what in hell does he want from me?”

“He said he wants to sell you some life insurance,” Ito explained. “He said nobody else would do you such a favor. Because, he said, you’re a terrible risk.”

I

DON’T SEEM TO REMEMBER

writing

Strange Embrace.

Oh, I know it’s mine. I can tell by flipping through it that I did indeed write it, and in fact I remember having written it. But I have no recollection of being at work on the book, or where I was when I wrote it. I’m pretty sure I know what I was paid for writing it—$1000, as I recall, which would come to $900 for me and $100 for Scott Meredith, who was representing me at the time. I know there were never any royalties (or if they were, they were all for Scott Meredith.) I’ve learned through the miracle of Google Books that an Australian edition was published, with the title changed to

Act One: Murder!

and Ben Christopher’s name on the cover, and that never brought me a dime, or the Aussie equivalent thereof.

I’m not complaining, mind you. Just letting you know what I remember, and what I don’t.

Strange Embrace

started life as an assignment, which came to me from Beacon Books via Scott Meredith. What they wanted was a mystery novel of 50,000 words or so based on a TV series called

Johnny Midnight.

Edmund O’Brien played Johnny, a theatrical producer with a wise–cracking Japanese houseboy. The series ran for 39 episodes in 1959–60, which is to say it ran for a year. Back then you ran new stories for nine months and then gave way to a summer replacement. Nowadays a full season is what, 26 episodes? 22?

Well, it turns out that 39 episodes of

Johnny Midnight

was more than enough. Edmund O’Brien’s girth may have had something to do with this. He’d put on a substantial amount of weight since he starred in the noir film classic,

D.O.A.

, and the producers of the TV show tried to save things by putting the poor sonofabitch on a crash vegetarian diet. He may have lost a pound or two, but he didn’t pick up many viewers, and the network waved bye–bye after a single season.

Now this was not the first TV show shot out from under me. That distinction belongs to

Markham,

which starred Ray Milland, and which also quit the airways after a single season. And,

mirabile dictu

, both of these TV wonders emanated from the same studio. (Revue, back then, later Universal Studios.)

What exactly did they want me to do?

Beacon Books wanted me to write a tie–in novel. I’d be making use of the characters from the TV series and fashioning an original plot for them. There were a lot of TV tie–in novels back then, and I guess they sold well enough, if the shows on which they were based were themselves popular. If not, not; if nobody would watch the show for free, why would anyone shell out 35¢ to read a printed version thereof?

So that was the assignment, and I said okay. Why not? I’d already done this sort of thing once by then.

In fact I’d done it twice. It was Belmont Books that commissioned

Markham,

and I sat down and wrote it, and it turned out rather well. At least I thought so, and I showed it to Don Westlake, and he thought so , too. and Henry Morrison (who represented me at Scott Meredith) read it and agreed with both of us, and sent it over to Knox Burger at Gold Medal, who bought it and paid me $2500 for it. I changed Roy Markham’s name to Ed London and called the book

Coward’s Kiss,

and Gold Medal changed the title to

Death Pulls a Doublecross

, and it came out in due course as the second book published under my own name. (It’s since been republished a few times, and it’s

Coward’s Kiss

once again. If you can just outlast the bastards, sooner or later you get to set things right.)

Then I had to fulfill my obligation to Belmont, and I wrote a book I called

Markham,

and they kept the title and added a subtitle:

The Case of the Pornographic Photos.

Isn’t that catchy? It sounds like Nancy Drew gone wrong. It’s now available as an Open Road ebook with the title I gave it when a paperback publisher reprinted it some years ago:

You Could Call It Murder.

It has my name on it, but then it always did.

Strange Embrace.

I was living in New York when I wrote it, but whether it was just before or just after we moved from 110 West 69

th

Street to 444 Central Park West I couldn’t tell you.

I do know this much: By the time I delivered the book, which wouldn’t have been more than three weeks after I started work on it,

Johnny Midnight

was history. The same fate fell upon

Markham

, but Belmont went ahead and published it all the same, fulfilling their agreement with Revue, and perhaps figuring that the Ray Milland connection wouldn’t hurt the book’s chances, even if the series was toast. Maybe there was no way to get out of their contract with Revue. Who knows? The series was dead, but the book went to the printer all the same.

It was a different story at Beacon. They had to buy the book, they were fine with the book, but why pay money to a TV studio to tie in with a piece–of–shit series that nobody watched in the first place? So one of their editors went to work, changing Johnny’s last name from Midnight to Lane. (Hey, why not? It could have been worse. “There but for the grace of God goes Johnny Daybreak.”)

They hung their own title on it. I’d called it

Johnny Midnight,

imaginatively enough, and they picked

Strange Embrace,

which gave me a titular hat trick—three novels under three different names, each with the word

strange

in it. (

Strange Are the Ways of Love

, by Lesley Evans;

A Strange Kind of Love

, by Sheldon Lord; and, duh,

Strange Embrace

, by Ben Christopher.) Each title was the publisher’s contribution. Nobody asked me.

Neat, huh? I’d have to call it weird. Even eerie. Or—what’s the word I’m looking for?

Oh, right.

Strange.

About the pen name.

Why did I use one? If my first tie–in novel,

Markham,

was respectable enough to have my own name on it, why slap a pen name on

Johnny Midnight?

I don’t remember what I was thinking at the time, but my guess is that it had something to do with the publisher. Beacon was a pretty cheesy house, a second–rate publisher of soft–core erotica, and who would put his own name on a Beacon book? (Well, Charles Willeford would and did, but then it’s hard to find a rule to which Charles wasn’t an exception. Fine man, brilliant writer, and

sui generis

as all get out.)

But why Ben Christopher?

Right around this time, my great good friend Don Westlake also wrote a TV tie–in, and used the name Ben Christopher on it. It was, he said, his name for tie–ins. Well, how would it be if I used it for one of mine? He said it would be fine, because he figured he was done with it, and done with tie–ins.

So just now I tried to find out what tie–in novel Don did, and it turned out he didn’t—not a book, that is. He seems to have used the name one time only, on a story that appeared in

77 Sunset Strip Magazine

. It was very likely the lead story, unquestionably a tie in, and probably novella length. But it wasn’t a book. I seem to be the only person to have used the name Ben Christopher on a book.

Strange, innit?

Lawrence Block (b. 1938) is the recipient of a Grand Master Award from the Mystery Writers of America and an internationally renowned bestselling author. His prolific career spans over one hundred books, including four bestselling series as well as dozens of short stories, articles, and books on writing. He has won four Edgar and Shamus Awards, two Falcon Awards from the Maltese Falcon Society of Japan, the Nero and Philip Marlowe Awards, a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Private Eye Writers of America, and the Cartier Diamond Dagger from the Crime Writers Association of the United Kingdom. In France, he has been awarded the title Grand Maitre du Roman Noir and has twice received the Societe 813 trophy.

Born in Buffalo, New York, Block attended Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio. Leaving school before graduation, he moved to New York City, a locale that features prominently in most of his works. His earliest published writing appeared in the 1950s, frequently under pseudonyms, and many of these novels are now considered classics of the pulp fiction genre. During his early writing years, Block also worked in the mailroom of a publishing house and reviewed the submission slush pile for a literary agency. He has cited the latter experience as a valuable lesson for a beginning writer.

Block’s first short story, “You Can’t Lose,” was published in 1957 in

Manhunt

, the first of dozens of short stories and articles that he would publish over the years in publications including

American Heritage

,

Redbook

,

Playboy

,

Cosmopolitan

,

GQ

, and the

New York Times

. His short fiction has been featured and reprinted in over eleven collections including

Enough Rope

(2002), which is comprised of eighty-four of his short stories.

In 1966, Block introduced the insomniac protagonist Evan Tanner in the novel

The Thief Who Couldn’t Sleep

. Block’s diverse heroes also include the urbane and witty bookseller—and thief-on-the-side—Bernie Rhodenbarr; the gritty recovering alcoholic and private investigator Matthew Scudder; and Chip Harrison, the comical assistant to a private investigator with a Nero Wolfe fixation who appears in

No Score

,

Chip Harrison Scores Again

,

Make Out with Murder

, and

The Topless Tulip Caper

. Block has also written several short stories and novels featuring Keller, a professional hit man. Block’s work is praised for his richly imagined and varied characters and frequent use of humor.

A father of three daughters, Block lives in New York City with his second wife, Lynne. When he isn’t touring or attending mystery conventions, he and Lynne are frequent travelers, as members of the Travelers’ Century Club for nearly a decade now, and have visited about 150 countries.

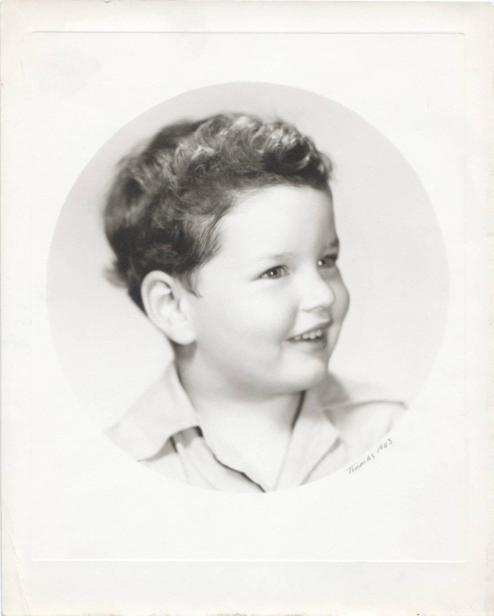

A four-year-old Block in 1942.

Block during the summer of 1944, with his baby sister, Betsy.

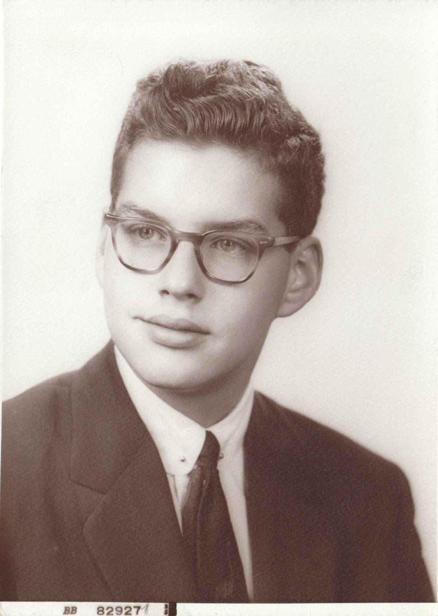

Block’s 1955 yearbook picture from Bennett High School in Buffalo, New York.