Strength to Say No

Read Strength to Say No Online

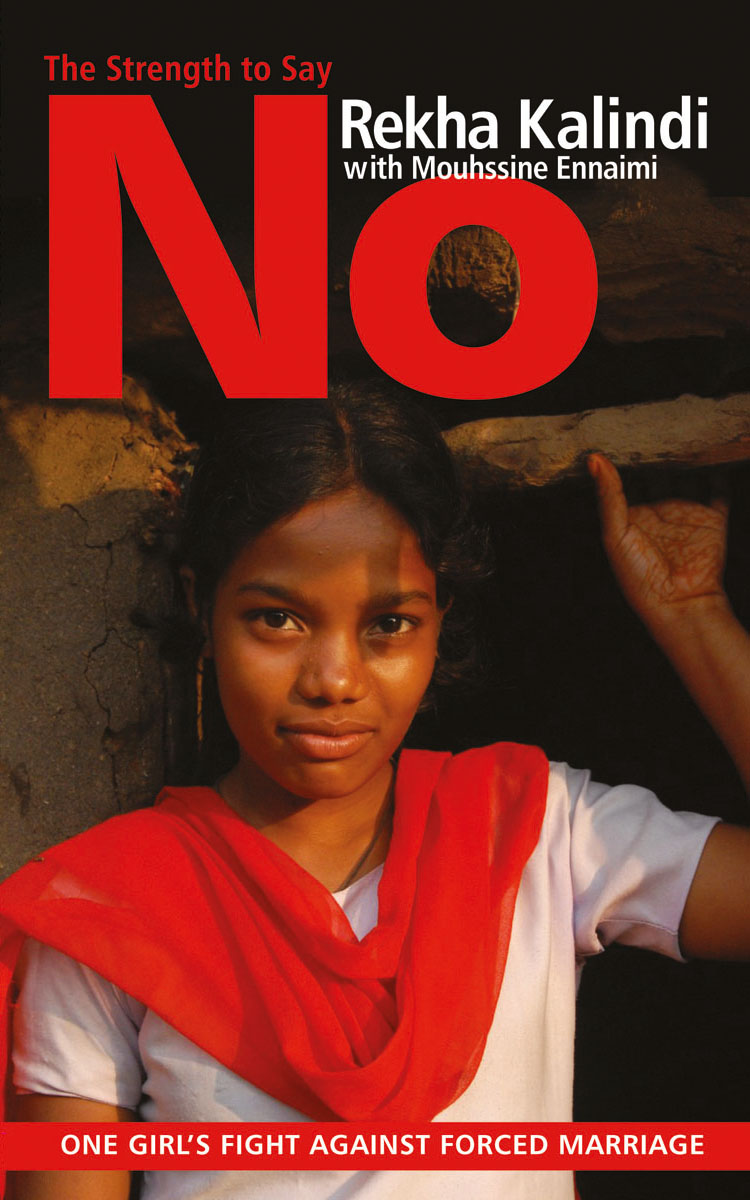

Authors: Mouhssine Rekha; Ennaimi Kalindi

THE STRENGTH TO SAY NO

REKHA KALINDI was born into a poor family in a village in West Bengal in 1997. From a young age she was obliged to give up her education to work and help bring in money to feed her family. Going back to school with the assistance of the Indian National Child Labour Project, she became a model pupil. However, at the age of eleven her parents said they had found her a husband. She staunchly opposed this, flying in the face of age-old custom and bringing her into conflict with her family. Only through the intervention of her teachers and the Minister of Labour of West Bengal was she able to continue her schooling. Since her story became known she has become a voice for millions of young people in India denied the opportunity to receive an education and have a proper childhood. She now travels all over India to speak, and her international profile continues to grow. Her story was one of only twenty (that of Anne Frank and Malala Yousafzai were two others) included in a book called, in English,

Children Who Changed the World

published to mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of the Child, and she is the recipient of India's National Bravery Award.

MOUHSSINE ENNAIMI is a distinguished correspondent for Radio France, widely acknowledged as a specialist on India. His posting to South Asia led to a meeting with Rekha Kalindi and their collaboration on this book.

Arranged marriages are extremely widespread in Indian society, and these arranged unions frequently merge into forced marriages. This ancient cultural tradition then produces forced marriages that deprive the young couple of their individual liberty in flagrant violation of the rights of man and of the child according to the United Nations and Unicef. More than 40 per cent of the forced marriages in the world take place in India. This is a national curse that the authorities are trying to root out.

In spite of a clear and precise legislative arsenal (the Child Marriage Restraint Act of 1929 â popularly known as the Sarda Act) traditions are tenacious: girls and boys are always subject to their parents' decisions from the moment that their marriage comes up for discussion. The main motivations that drive parents to choose the future wife or husband of their children are respect for caste and social class, the patronymic and dynastic line and economic considerations. These arrangements are sometimes made without the children ever having met one another, or when they have met only briefly. The minimum legal age for marriage is eighteen for women and twenty-one for men, but this is ignored, neglected and sometimes not known, even by the privileged classes.

Children who are sometimes married off for reasons of economic survival (one less mouth to feed) are deprived of their liberty, separated from their friends, isolated from the rest of their family and forced to abandon their schooling. As for health, such

children are more likely to be exposed to sexually transmitted diseases. A pregnancy during teenage years or earlier incurs the risk of causing serious after-effects on the female reproductive organs and the death of the infant and its mother during childbirth. The risk of death for the baby is 60 per cent greater when the mother is under the age of eighteen (source: United Nations). In India two out of five women are married before the legal age, and one in five before the age of fifteen. Furthermore the figures apply to all the childbirths in the population regardless of caste or education (source: âThe Situation of Children in India in June 2011', Unicef).

Of course, Rekha Kalindi did not know these statistical data any more than she knew that the rate of infant mortality in India is one of the highest in the world (higher than that in sub-Saharan Africa). However, her personal experience convinced her that an early marriage inevitably means damage to a girl's health as well as exclusion from the school system.

Mouhssine Ennaimi

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

All photographs by Mouhssine Ennaimi

Rekha Kalindi was just eleven years old when she met former Indian president Pratibha Singh Patil

Rekha cycling through her home village of Bararola

Rekha and all her family in Bararola village

Rekha at the door of her sister Josna's home

A teacher congratulates Rekha following a talk at a school

MEETING THE PRESIDENT

We were warned from the moment we went in. Don't look her in the eye, don't try to approach her and, most of all, be polite. This person, who I didn't even know existed until a few days ago, is the most important and the most respected person in the country. I could hardly believe that it could be a woman and furthermore that she wanted to meet me.

We go through the gardens before getting to the marble porch. We arrive in a luxurious room in which the carved walls are inlaid with symmetrical patterns. My new sandals slip on the white marble floor. I hitch up my long scarf-like

dupatta

so that I won't trip over it. The route we take is lined with pillars as big around as elephants' legs. The golden patterns of the mosaics sparkle from the combined reflection of sunlight and lit lamps. I fix my eyes on the doorway opposite to avoid being dazzled by all this light. I have never seen such a beautiful residence. Two armed guards stand motionless in front of our passage without, however, taking their eyes off us.

We cross a patio where we are received by several members of the security guard wearing uniforms of dark-grey shirts and trousers. One of the bodyguards speaks in Hindi into a walkie-talkie. I understand only part of the exchange. The women are called into an adjacent room. The women security guards in dark grey search us one by one. They ask us if we have electronic objects, pens or any other accessories in our possession. I reply

politely in the negative. The frisking is embarrassing, and I glance at my friends and smile to make light of this ordeal. We get through a gate and find ourselves again on the patio. The men are put through the same treatment. Cameras and mobile phones are confiscated. My father is given a more rigorous search than the others. I go towards him, but the guards ask me to stay to one side. They have found some bidis â little cigarettes hand-rolled in a eucalyptus leaf â in my father's pockets. Although he maintains that he has no matches the guards search for anything that could produce fire, but in vain. The man takes up his walkie-talkie again to talk to his colleague. I gather that we can go on.

The floor is covered with a thick carpet with a floral pattern. There is no longer any risk that I'll slip. On the contrary, my sandals catch on it and now I have to be careful not to lose them. I look at the chandeliers hanging from the ceiling and I think to myself that they must weigh as much as a cow. The table in the middle is spread with a brilliant white tablecloth that almost touches the floor. Light-blue ribbons encircle the backs of the chairs. A man is standing behind each of the covered dishes. We are told that after we've met the president we can eat as much as we like. As I cross the room I notice that the vegetarian dishes are separated from the dishes with meat: the two buffet tables are several metres apart. We walk through umpteen rooms, one after the other. I wonder how many people live in this house.

Other guards are posted in front of a door made of dark, shiny wood. These men are wearing a different outfit, red and white, and they are not armed, unlike the ones who have been accompanying us since the beginning and who searched us

meticulously. There are several double doors â to the right, the left and straight ahead. Each one of them is guarded by men wearing yet another uniform. There is a large chair, a microphone and several rows of smaller chairs. The guards talk to my parents, as well as to the people from the National Child Labour Project (NCLP) who supervise us in Purulia.

âThere is a protocol, and you must respect it to the letter,' our tutor informs us. âYou mustn't speak to her before she addresses you, nor go too close to her, nor look her in the eye. You must not touch her feet as you're used to doing with your parents or your teachers. Confine yourself to a simple and respectful hello in Hindi â

namaste

. Also don't forget that you must wait until she is seated and tells you to sit. Pay attention and never interrupt her, and don't forget to say “ma'am” after anything you say to her.'

I look at my friends Afsana and Sunita. They look tense. My father is squeezed into his jacket and doesn't seem very relaxed either. There are a lot of people in the room â other people that I don't know â and most of them are wearing suits and ties. There are journalists and some of them have made the trip with us from Purulia. Prosenjit, our tutor, comes up and reminds us that we have to have perfect manners in front of the president. He seems to be nervous and overexcited at the same time.

The door opens, and I finally see the person I've been hearing about non-stop for several days. She is Pratibha Patil, the first woman president of India (from 2007 to 2012) and before that the first woman governor of Rajasthan. She has a nice face, little glasses and undoubtedly one of the most beautiful saris that I have ever seen. She is followed very closely by four armed men responsible for her protection. She comes

up to me, and I put my hands together and bow my head. The president puts her hand on my shoulder.

âWhat's your name?'

âRekha. Rekha Kalindi, ma'am.'

âI am very proud of you and very proud to meet you,' she says, taking my hand in both of hers.

âThank you very much, ma'am,' I say, moved and nervous at the same time. I don't even think to tell her that I am honoured and proud to meet her in this palace.

âYou are an example to a whole generation and for millions of girls â¦' The president speaks to me without this famous protocol that has been drummed into me from the beginning. She strokes my hands, while all the time looking me in the eye. I thank her for welcoming us in this house, and she smiles.

When she gets to Sunita and Afsana she just joins her hands to greet them. They have a brief conversation, and she thanks them for coming so many miles to be in New Delhi today. The president also greets my father, the mothers of my friends and the rest of the NCLP personnel. When she is seated we sit down, too.

The president tells us that she read our story in the local papers. She couldn't believe her eyes. âSome girls have succeeded where government policy has been failing for thirty years.' She asked local staff to find out more about us. Ever since she received the findings and the confirmation of our experiences she was eager to meet us. I believe that she really meant it when she described us as heroines.