Stripping Down Science (25 page)

Read Stripping Down Science Online

Authors: Chris Smith,Dr Christorpher Smith

In what turns out to be an amusing example of nominative determinism, Cambridge University researcher Christopher Bird and his colleague Nathan Emery

86

challenged four peckish rooks (relatives of crows) called Cook, Fry, Connelly and Monroe, to serve themselves a tasty treat in the form of a worm floating out of reach in an upright tube of water. The birds needed to work out how to raise the water level in the tubes by

shovelling in stones that were lying nearby to bring the worm within pecking distance. Although none of them had seen this precise experimental set-up before, and this particular species is not known for using tools in the wild, they all quickly solved the problem.

In an added twist, when the researchers varied the water level in the tubes they found that the birds would initially size up how many stones they thought they would need and first drop in that number before making any attempt to retrieve the worm. Also, when the four rooks were offered a choice between using large and small stones, they invariably selected the large ones, having realised that these raised the water level more quickly. The researchers point out that the birds never added further stones to the tubes once they had successfully plucked out the worm, indicating that they genuinely saw the stones as a means to a meal, rather than performing the act for any other reason.

To prove that the birds were really learning from and reacting to the results of their efforts, the researchers included a tube containing sawdust in place of water. The rooks quickly realised that in this setting, the stones made no difference to

the height of the worm, so they stopped dropping them in. This shows that just like their close relatives the crows and jays, which have been labelled by some as âfeathered Einsteins', rooks also possess a remarkable aptitude for problem solving. They owe their intellect, as do other corvid (crow) family members, to their large brains which, relative to their body sizes, put them at par with a chimpanzee.

One other unusual feature of this bird family is that they possess the rare (amongst animals) ability to recognise themselves in a mirror. Most animals â human babies included â when presented with their own reflections are fooled into thinking they are seeing another individual and respond with displays of interest or aggression. Despite multiple exposures, they never seem to learn that they're staring at themselves. But so-called âhigher' animals, including chimps, dolphins and elephants, don't fall for this trick and neither, it now turns out, does another crow relative, the European magpie. This discovery was made recently by Helmut Prior, from Goethe University in Germany.

87

He made small red or yellow marks on the neck feathers of Lilly, Harvey, Gerti, Schatzi and the somewhat oddly named Goldie, five magpies in his laboratory. When the black-and-white birds were placed in front of a large mirror, they scratched at the marks on their feathers. As soon as they successfully removed them, the scratching stopped, indicating that they realised that the reflection was their own image and suggesting that they may have what scientists call a âtheory of mind'.

Other experiments have shown that animals of this family also have a strong sense of time and can remember the past and use that knowledge to plan for the future. Working with scrub jays, Cambridge scientist Nicky Clayton

88

built the crow equivalent of a hotel, with a dining room where âresidents' were always fed and a sleeping room where they were locked at night. After a few stays in the hotel, the birds realised that once they were shut into the sleeping area, there was no further access to food. Their solution? On subsequent occasions, as soon as they were fed in the dining room, they would sneak into

the sleeping area and hide a tasty treat or two, on the off chance they might be in the mood for a midnight feast later!

Some crow family members are also known to be impressive toolmakers, but researchers at Oxford University were still gobsmacked when a New Caledonian crow they were studying called Betty picked up a piece of straight wire and bent it into a hook in order to retrieve an object lodged at the end of a pipe. Alex Kacelnik and his colleagues

89

had given Betty, and a second male crow called Abel, a choice between either a straight or hook-shaped piece of wire to see which they would use to retrieve a snack. But when Abel got in a flap and stole the more useful hook-shaped wire, Betty made her own. According to Professor Kacelnik, âAlthough many animals use tools, purposeful modification of objects to solve new problems, without training or prior experience, is virtually unknown'.

But the icing on the cake must be the canny crows filmed in Japan by David Attenborough for his

Life of Birds

television series. In this instance, crows in Tokyo had learned to make use of

traffic lights and pedestrian crossings across the city to unlock a new source of food â previously impenetrable nuts. Having collected a kernel, a bird would drop it onto the road into the path of the oncoming traffic, close to a crossing. It would then wait patiently for a car to crush it open. Once this had happened, and at the next convenient gap-in-the-traffic juncture â usually when the lights were red, the crow would hop down and retrieve its titbit. Initially just a few of the animals were at it, but quickly they learned the trick from each other until it was common crow knowledge!

FACT BOX

Don't mock my memory

It's not just crows that are endowed with an impressive intellect: other birds have been shown to possess remarkable memories too, including mockingbirds.

In a recent study, University of Florida

Gainesville researcher Douglas Levey

90

asked a human volunteer to repeatedly disturb a pair of nesting mockingbirds over several days while he monitored the birds' responses. (Sensible chap. If I were the volunteer, I'd have asked to swap!) Predictably, with each successive incursion close to their nest, the birds made increasingly exaggerated responses, including making more frequent attacks on the approaching human on day four compared with day one.

One might predict, therefore, that a second â unknown â human approaching the nest on day four would elicit the same vigorous response from the birds, reflecting their generalised state of alarm. Instead, when a second researcher independently approached the nest, the birds reacted relatively mildly as they had done towards the first person the first time he had approached.

This shows that the birds were able to learn very quickly to recognise and distinguish

between different humans who approached their nests. While this sort of behaviour has been seen before amongst social mammals and livestock, and between individuals of the same bird species, birds discriminating between different members of an entirely different species had never previously been reported.

This is important, Levey says, because growing human populations are leading to increased human encroachment into the habitats of many animals. Under these circumstances some species âurbanise' very well, others less so. The ones that tend to do well under these crowded human-dominated conditions could be those with the sorts of natures displayed by these mockingbirds â the ability to size up, discriminate and react accordingly to different levels of threats, rather than in a one-size-fits-all fashion, which would almost certainly be deleterious to them in the long run â or should that be flight â¦?

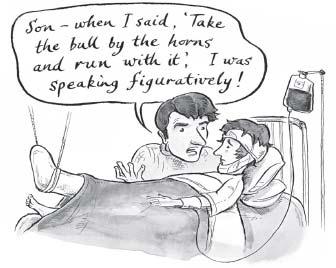

âDon't talk to strangers,' your mother always admonished, along with advice about trusting your instincts and believing in yourself and your own judgement. But this early age brainwashing to ignore the opinions of others in the name of self-belief looks to be bad advice, because a recent study â that had Harvard students speed dating in the name of science â has shown that phoning a friend, or even asking a stranger, will probably provide you with a far more accurate insight into how you will react to future events than if you rely only on your own intuition.

Most of us believe that we are sufficiently well acquainted with our own minds and bodies to make a pretty reasonable assessment of how we'd behave in a given situation. But intuitive and logical as this sounds, surprisingly, it's wrong. Worse still, it appears that we also resolutely refuse to accept the fact.

To prove this, Harvard psychologist Daniel Gilbert

91

set up a study in which he asked 33 female

students to go on five-minute âspeed dates' with one of eight male students. Half of the women, before embarking on the date, were first shown a profile of the man they were going to meet, including his photograph, details about what films, music and books he liked, where he lived and what he was studying. The other half of the women were shown only a report from another woman indicating â on a numerical scale â how much she had enjoyed the interaction with that particular man. Both groups then predicted how much they would enjoy the date, before being taken individually to meet the man in question for five minutes. Afterwards, both women were then asked again to ârate their dates'.

Incredibly, when the before and after ratings were compared, the women who had been given only the reports of another woman's experience with the same date before making their anticipated enjoyment predictions were found to have been far more accurate than the women who had been given the full profiles of the men before they met them. In fact, the amount by which the women were âout' in their predictions was nearly 50% lower when they had seen only the report from another woman.

Ironically though, three-quarters of these women nonetheless said that they felt they would have made more accurate predictions about their date if they had seen the full profile.

So does this relate just to a date, or does it apply to other life events too? To find out, David Gilbert set up a further experiment in which he asked a group of volunteers to write a short story which, he told them, would be used to determine which of three personality types they fitted into, A to C, where A was good, B was neutral and C was negative.

In reality, everyone was told they were personality type C, someone who sacrifices their beliefs for an easy life and eschews a challenge.

This was intended to provoke feelings of mild unhappiness amongst the volunteers. Groups of students were then shown either detailed descriptions of the personality types and asked to predict how they would feel if they were rated as each type, or they were shown the response from another volunteer rated previously as personality type C before being asked to predict their own response if they were labelled likewise.

Just like the dating experiment, the students given the reactions of other individuals to look at first were far more accurate â by 63% â in their assessments of how they would feel when they were rated as personality type C, compared with the individuals given the detailed personality descriptions. In this regard, maybe our mothers have âmyth-led' us when they advised against consulting strangers. Instead, they should have referred us to the work of the writer François de La Rochefoucauld, who pointed out in the 17th century, âBefore we set our hearts too much on anything, let us first examine how happy those are who already possess it.'

Despite our hunger for information, knowledge isn't necessarily power, but the opinion of another human being is priceless.