Stuka Pilot (22 page)

Authors: Hans-Ulrich Rudel

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #World War II, #War & Military

Meanwhile telegrams of congratulations have been pouring in from every point of the compass, even from members of the Reich government. It is going to be a hard fight to obtain leave to continue flying. The thought that my comrades are getting ready for another sortie and that I have to go to Odessa upsets me. I feel like a leper. This rider to the award disheartens me and kills my pleasure at the recognition of my achievement. In Odessa I learn nothing new, only what I already know and do not wish to hear. I listen to the words of congratulation absently; my thoughts are with my comrades who do not have this worry and can fly. I envy them. I am to proceed immediately to the Führer’s headquarters to be personally invested with the Diamonds. After stopping off at Tiraspol we change over to a Ju. 87—if only Henschel were with me, now Rothmann sits behind. Over Foskani—Bucharest—Belgrade—Keskemet—Vienna to Salzburg. It is no every-day occurrence for the Head of the State to receive an officer reporting in soft fur flying boots, but I am happy to be able to move about in them, even though in great pain. Wing Commander von Below comes in to Salzburg to fetch me while Rothmann goes home by train, it being agreed that I shall pick him up in Silesia on my way back.

For two days I bask in the sun on the terrace of the Berchtesgadener Hotel, inhaling the glorious mountain air of home. Now gradually I relax. Two days later I stand in the presence of the Führer in the magnificent Berghof. He knows the whole story of the last fortnight down to the minutest detail and expresses his joy that the fates have been so kind, that we were able to achieve so much. I am impressed by his warmth and almost tender cordiality. He says that I have now done enough; hence his order grounding me. He explains that it is not necessary that all great soldiers should lay down their lives; their example and their experience must be safeguarded for the new generation. I reply with a refusal to accept the decoration if it entails the stipulation that I may no longer lead my squadron into action. He frowns, a brief pause ensues, and then his face breaks into a smile: “Very well, then, you may fly.”

Now at last I am glad and happily look forward to seeing the pleasure in the faces of my comrades when they hear that I am back. We have tea together and chat for an hour or two. New technical weapons, the strategic situation, and history are the staple of our conversation. He specially explains to me the V weapons which have recently been tried out. For the present, he says, it would be a mistake to overestimate their effectiveness because the accuracy of these weapons is still very small, adding that this is not so important, as he is now hopeful of producing flying rockets which will be absolutely infallible. Later on we should not rely as at present on the normal high explosives, but on something quite different which will be so powerful that once we begin to use them they should end the war decisively. He tells me that their development is already well advanced and that their final completion may be expected very soon. For me this is entirely virgin ground, and I cannot yet imagine it. Later I learn that the explosive effect of these new rockets is supposed to be based on atomic energy.

The impression left after every visit to the Führer is enduring. From Salzburg I fly the short distance to Görlitz, my home town. All the receptions given in my honor are more of a strain than some operational sorties. Once when I am lying in bed at seven o’clock in the morning a girls’ choir serenades me; it requires a good deal of persuasion on the part of my, wife to make me say good morning to them. It is hard to explain to people that in spite of being decorated with the Diamonds one does not want any celebrations or receptions. I want to rest and that is all. I spend a few more days with my parents in my home village in an intimate family gathering. I listen to the news bulletins from the East on the wireless and think of the soldiers fighting over there. Then nothing holds me back any longer. I ring up Rothmann at Zittau and a Ju. 87 flies over Vienna—Bucharest southwards to the Eastern Front once more.

14. FATEFUL SUMMER 1944

A

few hours later I land at Foscani in the North Rumanian zone. My squadron is now stationed at Husi, a little to the north. The front is very much more firmly held than it was a fortnight ago. It runs from the Pruth to the Dniester along the edge of the plateau north of Jassy.

The little town of Husi nestles among the hills. Some of these heights have extensive vineyard terraces. Are we in time for the vintage? The airfield is situated on the northern rim of the town, and as our billets are directly on the opposite side of it we have to go through the streets every morning on our way to dispersal. The population watches our activities with interest. When one talks to them they always show their friendliness. The representatives of the church especially maintain close contact with us, following the lead given by the bishop whose guest I often am. He is never tired of explaining that the clergy see in our victory the only possible chance of keeping religious liberty and independence, and that they long for it to come with the least possible delay. There are many tradesmen in the town, the place is full of little shops. This is very different from Soviet Russia which we have left so recently, where the middle class has vanished, swallowed up by the proletarian Moloch.

What especially strikes me as I walk through the town is the enormous number of dogs. To all appearances these hordes are masterless. They roam around and one meets them at every comer and on every square. I am temporarily quartered in a little villa with a vineyard, on one side of which flows a small stream where one can bathe. Whole processions of dogs wander through this vineyard in the night. They move in Indian file, in packs of twenty or thirty. One morning I am still abed when a huge mongrel looks in at my window with his forepaws on the sill. Behind him, likewise standing on their hind legs, are fifteen of his colleagues. They rest their forepaws on the back of the dog in front, all peering into my room. When I chase them away they slink off sadly and without barking, back to their restless prowling.

There is no shortage of food; we live well, for we receive our pay in leis, and even if there is not much worth buying there are always eggs. Consequently almost the whole of our pay is converted into eggs. Flg./Off. Stähler holds the record of egg-consumption among the officers; he puts away astounding quantities. On days when shortage of petrol makes it impossible to fly this new source of energy is immediately put to the test; the whole squadron, to a man, takes some form of exercise, generally a long cross country run, gymnastics and, of course, a game of football.

I still find these exertions painful because the soles of my feet are not yet quite healed and my shoulder hurts me if I move it injudiciously. But for the squadron as a whole these ultra-routine sports are a splendid recreation. Some, and I am the keenest among them, take advantage of this extra leisure to stroll in the mountain woods or to practice some other sport.

Usually we drive to the airfield for the take off between 4 and 5 A.M. On the far side of the town we always run into a huge flock of sheep with a donkey walking in front. The donkey’s eyes are almost completely covered by a long and straggling mane; we wonder how he can manage to see at all. Because of this mane we nickname him Eclipse. One morning as we squeeze past we tweak his tail in fun. The shock provides a whole series of reactions: first he lets fly with his hind-legs like a kicking horse, then remembering his asinine nature he stands stock still, and lastly his chicken heart begins to thump and he streaks off like the wind. The flock of sheep entrusted to his care of course understand nothing of this unusual contretemps, still less of the reason for his kicking and haring off. When they see that the donkey has left them in the lurch the air is filled with a pandemonium of bleating, and suddenly the sheep set off at a gallop in pursuit…

Even if we meet with heavy opposition on our first sortie we do not care, for we still see the picture of this comic animal performance and our hearts are light with the joy of living. This gaiety robs the danger of the moment of its meaning.

Our missions now take us into a relatively stabilized sector where, however, the gradual arrival of reinforcements indicates that the Reds are preparing a thrust into the heart of Rumania. Our operational area extends from the village of Targul Frumos in the west to some bridgeheads over the Dniester S. of Tiraspol in the southeast. Most of our sorties take us into the area north of Jassy between these points; here the Soviets are trying to oust us from the high ground round Carbiti near the Pruth. The bitterest fighting in this sector rages round the ruins of the castle of Stanca on the so-called Castle Hill. Time and again we lose this position and always recapture it.

In this zone the Soviets are constantly bringing up their stupendous reserves. How often do we attack the river bridges in this area; our route is over the Pruth to the Dniester beyond Kishinew and further east. Koschnitza, Grigoriopol and the bridgehead at Butor are names we shall long remember. For a short period comrades of the 52nd Fighter Wing are stationed with us on our airfield. Their C.O. is Squadron Leader Barkhorn who knows his job from A to Z. They often escort us on our sorties and we give them plenty of trouble, for the new Yak 3 which has made its appearance on the other side puts up a show every now and then. A group advanced base is operating from Jassy, from where it is easier to patrol the air space above the front. The Group Captain is often up in the front line to observe the cooperation of his formations with the ground troops. His advance post has a wireless set which enables him to pick up all R/T interchanges in the air and on the ground. The fighter pilots talk to one another, the fighters with their control officer, the Stukas among themselves, with their liaison officer on the ground and others. Normally, however, we all use different wave lengths. A little anecdote which the Group Captain told us on his last visit to our dispersal shows the extent of his concern for his individual lambs. He was watching our squadron approaching Jassy. We were heading north, our objective being to attack targets in the castle area which the army wanted neutralized after making contact with our control. We were met over Jassy, not by our own fighters, but by a strong formation of Lags. In a second the sky was full of crazily swerving aircraft. The slow Stukas were ill matched against the arrow-swift Russian, fighters, especially as our bomb load further slowed us down. With mixed feelings the Group Captain watched the battle and overheard this conversation. The skipper of the 7th Flight, assuming that I had not seen a Lag 5 which was coming up from below me, called a warning: “Look out, Hannelore, one of them is going to shoot you down!” I had spotted the blighter a long time ago, but there was still ample time to take evasive action. I dislike this yelling over the R/T; it upsets the crews and has a bad effect on accuracy. So I replied: “The one who shoots me down has not yet been born.”

I was not bragging. I only meant to show a certain nonchalance for the benefit of the other pilots because calmness in an awkward spot like this is infectious. The commodore ends his story with a broad grin:

“When I heard that I was no longer worried about you and your formation. As a matter of fact I watched the scrap with considerable amusement.”

How often when briefing my crews do I give them this lecture: “Any one of you who fails to keep up with me will be shot down by a fighter. Any one who lags behind is easy meat and cannot count on any help. So: stick closely to me. Flak hits are often flukes. If you are out of luck you are just as likely to be hit on the head by a falling slate from a roof or to fall off a tram. Besides, war is not exactly a life insurance.”

The old stagers already know my views and maxims. When the new-comers are being initiated they hide a smile and think: “He may be right at that.” The fact that they have practically no losses due to enemy fighter interception corroborates my theory. The novices must of course have some proficiency by the time they reach the front, otherwise they are a danger to their colleagues.

A few days later, for instance, we are out in the same operational area and are again attacking under strong enemy fighter interference. As the recently joined Plt./Off. Rehm follows the aircraft in front of him into a dive he cuts off the other’s tail and rudder with his propeller. Luckily the wind carries their parachutes into our own lines. We spiral round them until they reach the ground because the Soviet fighters make a regular practice of opening fire on our crews when they have bailed out. After a few months with the squadron Plt./Off. Rehm has become a first-rate airman who is soon able to lead a section and often acts as flight leader. I have a fellow-feeling for those who are slow to learn.

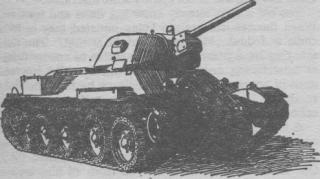

T 34

Plt./Off. Schwirblat is not so lucky. He has already 700 operational sorties to his credit and has been decorated with the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross. He has to make a forced landing after being hit in the target area just behind the front line and loses his left leg, as well as some fingers. We are to be together again in action in the final phase of the war.