Stuka Pilot (7 page)

Authors: Hans-Ulrich Rudel

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #World War II, #War & Military

“I know you are going to be mad at me for taking your aircraft, but as I am in command I must fly with the squadron. I will take Scharnovski with me for this one sortie.”

Vexed and disgruntled I walk over to where our aircraft are overhauled and devote myself for a time to my job as engineer officer. The squadron returns at the end of an hour and a half. No. 1, the green-nosed staff aircraft—mine—is missing. I assume the skipper has made a forced landing somewhere within our lines.

As soon as my colleagues have all come in I ask what has happened to the skipper. No one will give me a straight answer until one of them says: “Steen dived onto the

Kirov

. He was caught by a direct hit at 5000 or 6000 feet. The flak smashed his rudder and his aircraft was out of control. I saw him try to steer straight at the cruiser by using the ailerons, but he missed her and nose-dived into the sea. The explosion of his two thousand pounder seriously damaged the

Kirov

.”

The loss of our skipper and my faithful Cpl. Scharnovski is a heavy blow to the whole squadron and makes a tragic climax to our otherwise successful day. That fine lad Scharnovski gone! Steen gone! Both in their way were paragons and they can never be fully replaced. They are lucky to have died at a time when they could still hold the conviction that the end of all this misery would bring freedom to Germany and to Europe.

The senior staff captain temporarily takes over command of the squadron. I chose A.C. 1st class Henschel to be my reargunner. He has been sent to us by the reserve flight at Graz where he flew with me on several operational exercises. Occasionally I take some one else up with me, first the paymaster, then the intelligence officer and finally the M.O. None of them would care to insure my life. Then after I have taken on Henschel permanently and he has been transferred to the staff he is always furious if I leave him behind and some one else flies with me in his stead. He is as jealous as a little girl.

We are out again a number of times over the Gulf of Finland before the end of September, and we succeed in sending another cruiser to the bottom. We are not so lucky with the second battleship

Oktobreskaja Revolutia

. She is damaged by bombs of smaller calibre but not very seriously. When we manage on one sortie to score a hit with a two thousand pounder, on that particular day not one of these heavy bombs explodes.

Despite the most searching investigation it is not possible to determine where the sabotage was done. So the Soviets keep one of their battleships.

There is a lull in the Leningrad sector and we are needed at a new key point. The relief of the infantry has been successfully accomplished, the Russian salient along the coastal strip has been pushed back with the result that Leningrad has now been narrowly invested. But Leningrad does not fall, for the defenders hold Lake Ladoga and thereby secure the supply line for the fortress.

5. BEFORE MOSCOW

W

e carry out a few more missions on the Wolchow and Leningrad front. During the last of these sorties it is so much quieter everywhere here in the air that we conclude the balloon must be about to go up in some other part of the line. We are sent back to the central sector of the Eastern front, and as soon as we get there we begin to notice that the infantry is spoiling for action. There are rumors here of an offensive in the direction of Kalinin—Jaroslavl. Over the air bases Moschna—Kuleschewka we bypass Rshew and land at Staritza. Flight Lieutenant Pressler has replaced our late skipper as squadron commander. He comes from a neighboring wing.

Gradually the cold weather sets in and we get a foretaste of approaching winter. The fall in the temperature gives me, as engineer officer of the squadron, all kinds of technical problems, for suddenly we begin to have trouble with our aircraft which is only caused by the cold. It takes a long time before experience teaches me the answer to the problems. The senior fitters, especially, now have their worries when every one is doing his utmost to have the maximum possible number of aircraft serviceable. Mine has an accident as well. He is unloading bombs from a lorry when one of them tips over and smashes his big toe with its fins. I am standing close by when it happens. For a long time he is speechless; then he comments, gazing ruefully at his toe: “My long-jumping days are over!”

The weather has not yet become really cold.

The sky is overcast, but there are warmer currents again with low clouds. They are of no help to us in our operations. Kalinin has been occupied by our troops, but the Soviets are fighting back very bitterly and still holding their positions nearer the town. It will be difficult for our divisions to develop their advance, especially as the weather is of great assistance to the Russians. Besides, the incessant fighting has seriously reduced the strength of our units. Also our supply lines are not functioning any too smoothly, because the main communications road from Staritza to Kalinin runs right in front of the town in the hands of the enemy who exerts a continuous pressure from the East on our front line. I can soon see for myself how difficult and confused the situation is. Our effective strength in aircraft is at the moment small. The reasons are casualties, the effects of the weather, etc. I fly as No. 1—in the absence of the C.O.—in a sortie to Torshok, a railway junction N.W of Kalinin. Our objectives are the railway station and the lines of communication with the rear.

The weather is bad, cloud level only about 1800 feet. This is very low for a target with extremely strong defense. Should the weather deteriorate sufficiently to endanger our return flight we have been ordered to make a landing on the airfield near the town of Kalinin. We have a long wait for our fighter escort at our rendezvous. They fail to show up; presumably the weather is too bad for them. By waiting about in the air we have wasted a lot of petrol. We circuit round Torshok at a moderate altitude trying to discover the most weakly defended spot. At first it seems that the defense is pretty uniformly heavy, and then having found a more favorable spot we attack the railway station. I am glad when all our aircraft are in formation again behind me. The weather goes from bad to worse, plus a heavy fall of snow. Perhaps we have just enough petrol left to reach Staritza provided we are not forced to make too wide a detour because of the weather. I quickly decide and set course for the nearer Kalinin; besides, the sky looks brighter in the East. We land at Kalinin. Everybody is running round in circles in steel helmets. Aircraft from another fighter-bomber wing are here already. Just as I am switching on my ignition I hear and see tank shells fall on the airfield. Some of the aircraft are already riddled with holes. I hurry away in search of the operations room of the formation which has moved in here to obtain a more accurate picture of the situation. From what I learn we shall have no time to waste in overhauling our aircraft. The Soviets are attacking the airfield with tanks and infantry, and are less than a mile away. A thin screen of our own infantry protects our perimeter; the steel monsters may be upon us at any moment. We Stukas are a godsend to the ground troops defending the position. Together with the Henschel 123s of the fighter-bomber wing we keep up a steady attack on the tanks until late in the evening. We land again a few minutes after taking off. The ground personnel are able to follow every phase of the battle. We are well on the mark, for everybody realizes that unless the tanks are put out of action we have had it. We spend the night in a barracks on the Southern outskirts of the town.

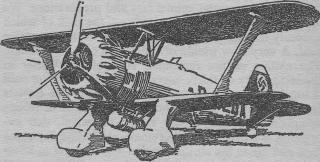

Henschel 123

We are startled out of sleep by a grinding noise. Is it one of our flak tractors changing position or is it Ivan with his tanks? Anything can happen here in Kalinin. Our infantry comrades tell us that yesterday some tanks drove into the market square, firing at everything that showed itself. They had broken through our outposts and it took a long time to deal with them in the town. Here there is an incessant thunder of gunfire; our artillery is in our rear shelling Ivan above our heads.

The nights are pitch dark with a low blanket of cloud. There is no air fighting except close to the ground. As once again the supply road has been cut the battle-weary ground troops are faced with many shortages. Yet they never falter in their superhuman task. A sudden cold snap of over forty degrees freezes the normal lubricating oil. Every machine gun jams. They say the cold makes no difference to the Russians, that they have special animal fats and preparations. We are short of equipment of every kind, the lack of which seriously impairs our effective strength in this excessive cold. A very slow trickle of supplies is coming through.

The natives cannot remember such bitter weather in the last twenty or thirty years The battle with the cold is tougher than the battle with the enemy. The Soviets could have a more valuable ally. Our tank troops complain that their turrets refuse to swivel, that everything is frozen stiff. We remain at Kalinin for some days and are in the air incessantly. We soon get to know every ditch. The front line has been pushed forward again a few miles to the East of our airfield, and we return to our base at Staritza where we have long been expected back. From here we continue operations, also in the direction of Ostaschkow, and then we are ordered to move to Gorstowo near Rusa, about fifty miles from Moscow.

Our divisions which have been thrown in here are pushing forward along the motor road through Moshaisk towards Moscow. A narrow spearhead of our tanks advancing through Swenigorod—Istra is within six miles of the Russian capital. Another group has also thrust even further Eastwards and has established two bridgeheads to the North of the city on the East bank of the Moscow—Arctic canal; one of them at Dimitrov.

It is now December and the thermometer registers 40-50 degrees below zero (centigrade). Huge snowdrifts, cloud cover generally low, flak intense. Pit./Off. Klaus, an exceptionally fine airman and one of the few left of our old companions, is killed, probably a chance hit from a Russian tank. Here, as at Kalinin, the weather is our chief enemy and the savior of Moscow.

The Russian soldier is fighting back desperately, but he, too, is winded and exhausted and without this ally would be unable to stem our further advance. Even the fresh Siberian units which have been thrown into the battle are not decisive. The German armies are crippled by the cold. Trains have practically stopped running, there are no reserves and no supplies, no transportation for the wounded. Iron determination alone is not enough. We have reached the limit of our strength. The most needful things are lacking. Machinery is immobilized, transport bottle-necked; no petrol, no ammunition. Lorries have long since been off the roads. Horsedrawn sleighs are the only means of locomotion. Tragic scenes of retreat recur with ever greater frequency. We have few aircraft. In temperatures like these engines are shortlived. As previously when we had the initiative we go out in support of our ground troops, now fighting to hold the attacking Soviets.

Some time has passed since we were dislodged from the Arctic canal. We are no longer in possession of the big dam N.W. of Klin in the direction of Kalinin. The Spanish Blue Division after putting up a gallant resistance has to evacuate the town of Klin. Soon it will be our turn.

Christmas is approaching and Ivan is still pushing on towards Wolokolamsk, N.W. of us. We are billeted with the squadron staff in the local school and sleep on the floor of the big schoolroom; so every morning when I get up my nocturnal ramblings are repeated to me. One finds out that five hundred operational sorties have left their mark. Another part of our squadron is quartered in the mud huts common here. When you enter them you can imagine you have been transported to some primitive country three centuries ago. The living room has the definite advantage that you can see practically nothing for the tobacco smoke. The male members of the family smoke a weed which they call Machorka and it befogs everything. Once you have got used to it you can make out the best piece of furniture, a huge stone stove three feet high and painted a dubious white. Huddled round it three generations live, eat, laugh, cry, procreate and die together. In the houses of the rich there is also a little wooden-railed pen in front of the stove in which a piglet romps in pursuit and evasive combat with other domestic animals.

After dark the choicest and juiciest specimens of bug drop onto you from the ceiling in the night with a precision that surely makes them the Stukas of the insect world. There is a stifling frost; the Pans and Paninkas—men and women—do not seem to mind it. They know nothing different; their forebears have lived like this for centuries, they live and will go on living in the same way. Only this modem generation seems to have lost the art of telling stories and fairy tales. Perhaps they live too close to Moscow for that.

The Moskwa flows through our village on its way to the Kremlin city. We play ice hockey on it when we are grounded by the weather. In this way we keep our muscles elastic even if some of us are somewhat damaged in the process. Our adjutant, for example, gets a crooked nose with a slight list to starboard. But the game distracts our thoughts from the sad impressions over the front. After a furious match on the Moskwa I always go to the Sauna. There is one of these Finnish steam baths in the village. The place is, however, unfortunately so dark and slippery that one day I trip over the sharp edge of a spade propped against the wall and come a cropper. I escape with a nasty wound.