Summer in the South (19 page)

Read Summer in the South Online

Authors: Cathy Holton

Tags: #Fiction, #Contemporary Women, #Sagas, #Romance, #Contemporary

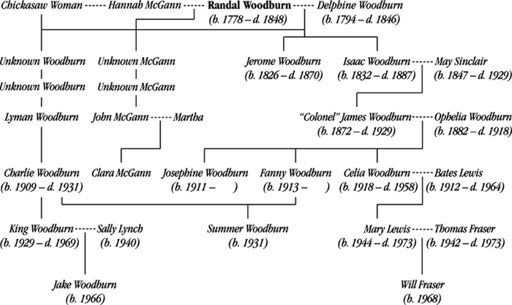

But she couldn’t. Instead, she thought of the way Maitland tenderly kissed Fanny’s hand as they sat watching television at night. She thought of the sepia-tinted Woodburn family photographs showing solemn, slightly menacing young men in slouch hats and boots, long rifles nestled in their arms. She thought of austere, taciturn Josephine, the keeper of the family history, the guardian of its honor, a woman who seemed capable of anything, even murder.

And later that night as she eased into sleep, as pale moonlight flooded her room and crickets chanted outside her window, she thought of doe-eyed Clara McGann tending her beautiful poisonous plants in the moonlit garden.

T

hat evening she suffered another attack of sleep paralysis.

She awakened to the sound of someone whispering her name. She could feel a presence in the room with her, although she could not turn her head to look. Her eyes were open and staring at the ceiling but she could not move them; she could not move any part of her body. She lay as if encased in a tomb of ice.

The blackness inside the room was thick, and smelled of smoke and old linen. As Ava stared upward, she became gradually aware of a dark shadow flitting across the ceiling at regular intervals. She was terrified by the fear that a strange face might lean, horrifyingly and without warning, into her field of vision.

The episode went on for several minutes and just as the feeling of dread became too much for her to bear, she found herself quite suddenly able to blink her eyes.

Instantly, as if released from a spell, she was able to move again, and she cried out.

She leaned to switch on a lamp. The room was empty, cheerful and cozy in the lamplight. Gradually her breathing evened. Her heart stopped its wild thudding and beat a calm, steady rhythm. One of the old plantation ledgers was lying on her bedside table and she pulled it into bed and curled on her side, cradling it.

The horror of the episode gradually faded. She opened the ledger and began trying to decipher the old-fashioned script. She read:

April 19th. Sunday. Did not go to church. Wind very fresh but no rain. Laramore and Phipps came around noon. Went down to the Negro houses and took five Negroes viz.—Peter, John, Sam, Titus, and Louisa. They are sold to a man near Carthage. They seemed in good spirits but I am loath to part with them through no fault of theirs, but by my own extravagance. This should pay my debts to Barnwell and Cuffy and leave some for the children’s tuition.

Spent the afternoon reading

Chevalier de Faublas.

It was horrible, the way someone could describe a human being as if they were of no more consequence than a cow. She had admired the Woodburns’ collection of artifacts, their wealth and prestige and history, and yet all those things had come at the price of human misery.

April 20th. The yard Negroes pulled up the floor of one of the outhouses and killed 60 rats. Clear and hot in the morning. The Negroes at home are disconsolate over the sale yesterday but they know it could not be helped. They may yet see their children again. Took a hunt with Sumner Whitson. Killed a very large buck. Bathed and dressed and rode over and dined with W. F. Fraser.

Wife sick again.

She flipped back to the opening page of the ledger.

1832

it read, in flowing script. Old Randal would have been master in those days. These were his words Ava was reading.

April 24th. Clear, calm, and beautiful. All hands planting cotton. While at supper, Old Judy came in crying that Toby was worse. Went down to the Negro houses and found him

perfectly dead.

They told me yesterday he was better and so I did not send for the doctor. Toby was a good boy, about 15 years old, and will be a great loss to me. He lost an eye last summer and was not the same after that, very dispirited and low. Taken sick on Tuesday, died Thursday.

Somewhere deep in the house Ava heard a steady thumping sound, a vague knocking. It went on for a minute or two, then stopped. She closed the ledger and lay back, thinking about the boy, Toby, who had died one hundred and sixty-six years ago. It was easy to imagine him, wounded and disheartened, going about his dreary life.

Had he welcomed death when it finally came?

The Negro houses were where the Harvard students had come to excavate several summers ago. The next time she was at Longford she would ask to see them, to see if she might catch some lingering presence of Toby, to walk where he had walked, to see what he had seen.

She wondered if Josephine and Will had ever read the plantation journals. She wondered how much of their family history they had truly been willing to face.

Longford

T

he following evening, Ava began her novel.

She was taking a bath in the old-fashioned claw-foot bathtub when a sentence came into her head:

He was tall and dark, and when he entered a room all eyes turned his way.

She climbed out of the tub, dressing quickly, and padded down the hallway. The house was quiet; the others had climbed the stairs to bed hours ago, and she went into her room and switched on the desk lamp. The room, beyond the dimly glowing light, was bathed in shadow. She sat at the computer and opened a new file, waiting as the glowing page loaded on the screen, and then without thinking about it too much, she began to write.

Time passed, but she was unaware of its passing; she was in turn-of-the-century New Orleans with a destitute boy and his mother. A boy she named Charlie Finn. She saw him and his mother step aboard a streetcar, saw them sit at a window and watch the scrolling scene, the ancient oaks draped in moss, the beautiful old houses lining St. Charles Avenue. She saw them climb down from the car and walk along the brick sidewalk to a grand white house that sat like a wedding cake behind a wrought-iron fence, taking up the entire block. She watched as Charlie and his mother, a seamstress, went in through the gate and around to the back of the house and rang the bell. Later they were shown through a series of large cool rooms, and up a back staircase to a room where the lady of the house sat waiting to be measured for new undergarments: lace-trimmed drawers and corset covers and chemises. Ava saw the boy, Charlie, with his large dark eyes and black hair, sitting quietly and patiently, waiting for his mother to finish. She saw his face as he looked around the large room with its expensive furnishings, saw his mother, weary and broken from work and poverty, on her knees before the lady of the house, her worn tape measure in her hands. She felt something stir in his chest then, something determined and fierce.

She saw him as an adolescent and then as a handsome young man, standing in front of his mother’s burial vault in Lafayette Cemetery.

And later, she watched as he drove triumphantly into Finn’s Crossing, the sun shining brightly on his dark hair and along the gleaming chrome of his Ford Model T Runabout. She saw his face on the day he first laid eyes on the beautiful Fanny Finn, strolling along the downtown street on the arm of her beau, Maitland Wallis. Charlie fell instantly, irrevocably in love with Fanny, determined, despite his lack of prospects and her social standing, to have her.

At three a.m. Ava stopped. She was tired, her eyes were dry, and her shoulders ached. Her whole body felt sore and heavy, as if she had run a great distance. She had written nearly six thousand words, and she had no clear recollection of how it had happened.

She shut the computer down and clicked off the lamp, and, climbing into bed, fell into a deep and oblivious sleep.

I

n the morning when she awoke, Will was there. He knocked on her door and entered carrying a cup of coffee in his hands. She sat up in confusion, looking around the bright, sunlit room.

“What time is it?”

“Nearly ten-thirty.” He set the coffee down on the bedside table.

“My God,” she said, yawning. “I had no idea.”

He sat down gingerly on the edge of the bed. She pushed herself up against the headboard, pulling her legs up and resting the steaming cup on one knee. Outside the window the trees made a lacy pattern on the screen.

“I came by to show you the list,” he said.

She sipped her coffee. “What list?” she said.

He stared out the window, his profile severe in the slanting light. “The invitation list,” he said. “For the party at Longford.”

“Oh, right.”

“You don’t have to help if you don’t want to.” He looked tired; the skin beneath his eyes was dark and dull, and there were lines around his mouth.

“Don’t be silly,” she said. “Of course I want to help.” She wasn’t bothered by his moods today. She was happy, remembering that she had begun her novel, remembering the work she had done last night. She smiled and put out her hand. Without a word, he gave her the list.

She looked it over carefully. She recognized very few of the names, although she had, no doubt, met everyone on it. Jake Woodburn, she noticed, was not listed.

She took a pen and added a name at the bottom, then gave it back to him.

He said, “Darlene Haney?”

“She’s been nice to me. You don’t mind, do you?”

“Invite whomever you like,” he said, folding the paper and sliding it back into his pocket. His manner was brusque, irritated.

“I started working last night.”

“Working?”

“On my novel. It just seemed to flow out of me, Will. It was incredible.”

He put his hands down on either side of him on the bed and looked at her. “That’s great,” he said mildly.

“And now I don’t want to stop. I want to keep going and see how far I can get.”

“Well, of course I don’t want to interfere with your work,” he said, sounding as if he would very much like to do just that.

She sipped her coffee. She was restless, wanting him to go, wanting to read over what she’d written last night to see if it was any good.

“I thought you might like to walk downtown with me to the stationers,” he said. “And maybe get some lunch afterward.” He hesitated at her expression. “Or not,” he added quickly.

She set her cup down, crawled over, and put a hand on his shoulder. “You don’t mind, do you? It’s just that I’ve got so much work to do. I want to get back to it while it’s fresh.”

His eyes in the slanting light were almost blue. There was a childlike quality about him that many women would have found endearing, but Ava did not. She was finished with men who ruled her with their moods and petty withholdings of affection. She had her work now, and that was all that mattered. She had caught a glimpse last night of what it could be like, the intoxication, the dreamlike abandonment.

“I don’t mind,” he said.

Yet she owed him a debt of gratitude. Her novel, her story was a gift from him, from his family. Not that she could tell him, of course; he would try to put a stop to it. Still, she owed him something. She opened her mouth to speak but stopped, her attention drawn suddenly to the mantel. She stared, feeling a vague sense of unease. She had left Clotilde’s vase resting on the left side of the mantel but now it was pushed to the far right.

The cleaning ladies

, she thought,

must have moved it.

He stood abruptly, causing her hand to drop. “I’ll see the caterer and take care of ordering the tables and chairs. I thought we’d set everything up in the dining room and front parlor.” He stood awkwardly beside the bed, his hands at his sides.

“Yes,” she said. “Yes, of course.”

His look was bitter, reproachful, as if he’d suspected all along that she’d let him down. “I’ll let you get back to work then,” he said.

And because she was grateful to him and because she felt guilty that she

had

let him down, she said insistently, “Let me do something! Please. I want to help.”

“You can order the table arrangements.”

“All right,” she said, her gazed fixed once more on the mantel. “I’ll order the flowers. Let me take care of that.”

And it wasn’t until after he had left, his footsteps echoing eerily down the hallway, that she realized,

My God, I sound like Clarissa Dalloway.

S

he had an absurd desire to please people. It was something about herself that had always driven Ava crazy.

In the beginning of her love affair with Jacob she had kept part of herself back. He was cheerful and vulgar, and she pretended a kind of bemused detachment, like an overindulgent mother with a spoiled child. But over time she lost her footing. It became a kind of competition between them, and she began to feel herself weakening, while he seemed to grow in strength and confidence. Unable to understand this relationship, she had finally seen a professional.

“I’ve tried to make myself over to please him and it isn’t working. He’s bored, I can feel it, and I don’t know if he loves me. He says he does but I wonder.”

“What about you? Do you love him?” The doctor, a bald and rather paunchy man, watched her with a benign expression.

She was quiet. “I want him to love me,” she said anxiously.

“And if he doesn’t, how would you feel?”

“Like a failure.”

Something had been exposed, a quivering nerve that seemed to run through the core of her.

Later, as she drove home through the rain, the words taunted her, clanging through her head like a fire alarm.

She did not see the doctor again.

H

aving begun the novel that she tentatively called

Old Money

, Ava found over the next two weeks that her days passed in a frenzy of creative activity. She rose around ten-thirty every morning, and after a quick breakfast and coffee, sat down at her desk to read over and rewrite what she’d written the day before. After lunch she would take a long walk around the garden, thinking about the scene she was preparing to write, and when she felt that she had it right, she would go in and sit down at the computer.

The novel ran through her head like a movie. The characters were so real she could picture the faint gleam of sweat along their upper lips, could smell the burnt-sugar scent of their starched clothes. Sometimes to help her set the scene she played music, Respighi’s “The Pines of Rome,” or Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue,” and more recently, Debussy’s “Preludes” for piano.

After supper she would return to her computer, writing long into the night when the house was quiet and shifting shadows settled in the corners of the room. She had read once of a historical novelist who wrote only by candlelight, feeling that the flickering light and the trancelike state it engendered transported her back to another time and place. Ava could certainly understand that now. Sitting in her darkened room, lit only by a desk lamp and the glowing screen of her computer, it was easy to find herself carried away.

And yet after two weeks of steady, relentless work, she found herself at an impasse.

Fanny has run away with Charlie and they are living in Finn Hall. But Fanny has begun to feel guilty over her betrayal of Maitland. She has begun to miss his company. And Charlie, too, has begun to feel adrift, living in the big house he has always dreamed of, yet surrounded by a family that despises him. It is only his love for Fanny that sustains him. He is handsome (when she closes her eyes Ava imagines Jake) and sociable, and the many parties he throws are an attempt to amuse Fanny, to bind her to him.

But she had it wrong, Ava realized. The story was too simplistic in a way that life never was. Being poor didn’t make Charlie “good” any more than being rich made Fanny “bad.” And yet Fanny’s upbringing would have influenced who she was, the decisions she made. As would Charlie’s. And what of Josephine, Clara, Maitland, and Charlie’s illegitimate child, King? What part might they have played in the tragic love story of Charlie and Fanny? A story that was becoming less clear, the morality more clouded, the more Ava wrote.

She couldn’t stop now, though. She had come too far. She could only hope that the characters would eventually reveal themselves, that their motives would emerge as she blundered along. She had only been writing two weeks and already she had almost eighteen thousand words. A phenomenal start. And Will, busy getting ready for the party at Longford, trying desperately to finish the kitchen renovation before then, seemed more than willing to let her spend her evenings working. Which was fine with Ava.

Sometimes though, in the middle of a particularly moving love scene, or more often as she imagined Charlie going about his daily routine, the sun shining on his black hair and dark eyes, she thought of Jake. She had not heard from him since that day at his mother’s house, although she had not really expected him to call. He had made it clear that he wanted no further trouble with the Woodburns. And neither did she. She could not imagine writing anywhere else but here in this fateful house.

She could not afford to be thrown out now, before the story had fully formed itself, materializing before her like a ghost.

A

va went out to Longford early to see if she could help Will get ready for the party but he seemed to have everything under control. He had obviously done this before. He and the caterer were on a first-name basis, and when he saw Ava he smiled at her distractedly and reminded her to put her things upstairs (she was spending the night). The buffet table had been set up in the room Will called the small parlor, and several large round tables had been set up in the dining room and front parlor. The tables were covered in white tablecloths and a mix of sterling silver pieces. White floral arrangements stood in silver vases in the center of each table: white tea roses, lilies, hydrangeas, and baby’s breath (Ava had let the florist suggest the flowers; she knew nothing of such things). Tea light candles were scattered among the flowers, and with the dimmed chandeliers and the faded wallpaper the rooms looked like something out of a

Martha Stewart Weddings

book.

Ava wandered around, amazed at the transformation Will had managed in the kitchen. He had installed a new bank of black cabinets and soapstone countertops, and the walls were covered now with dry-wall, although none of the finish work had been done. Still, the overall look was pleasing, and she could imagine what the room would look like when he was finished. Three women dressed in chef coats, members of the catering staff, introduced themselves to Ava. She wandered out onto the back gallery where the bar had been set up, smiling at the bartender, who was busily setting up glassware and stocking the shelves.

It was late June. The afternoon sun had begun to settle in the sky, and the heat was slowly waning. Long shadows lay over the grass. Over by the foundation where the old cabin once stood, birds sang in a clump of fig trees. Clusters of muscadine grapes hung from a long white trellis, separating the lawn from the distant rolling fields.