Summer of '49: The Yankees and the Red Sox in Postwar America

Read Summer of '49: The Yankees and the Red Sox in Postwar America Online

Authors: David Halberstam

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History, #Biography

Summer of ’49

David Halberstam

For David Fine

Contents

A Biography of David Halberstam

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.

—

J

OSEPH

C

AMPBELL,

The Hero with a Thousand Faces

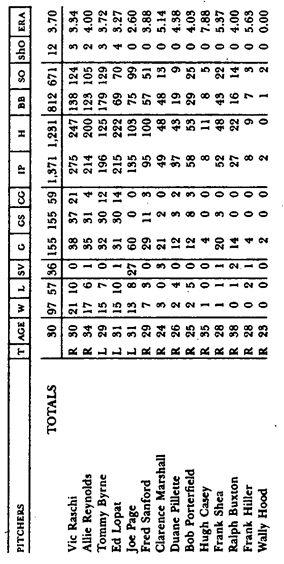

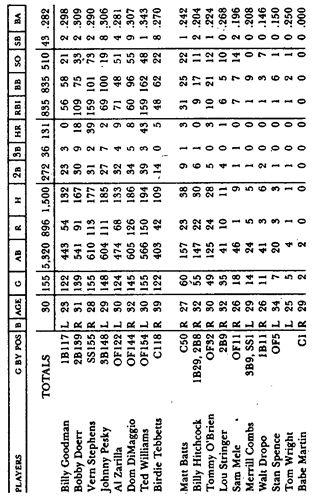

THE NEW YORK YANKEES OF 1949

Casey Stengel—Manager

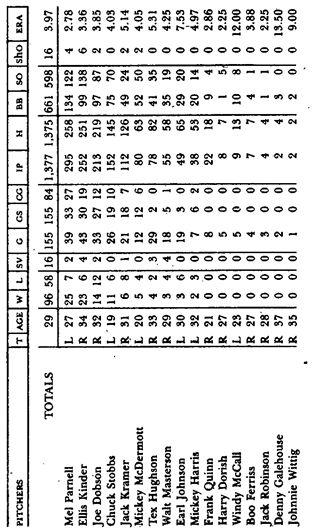

THE BOSTON RED SOX OF 1949

Joe McCarthy—Manager

PROLOGUE

I

N BOSTON THE EXCITEMENT

over the last two games of the 1948 season was unprecedented, even taking into account that city’s usual baseball madness. The fever was in the streets. On Saturday morning the crowd gathered early, not only inside Fenway Park, to watch the Red Sox and the Yankees in their early workouts but also outside the nearby Kenmore Hotel where the Yankees were staying—the better to get a close look at these mighty and arrogant gladiators who had done so much damage to the local heroes in the past. Such veteran Yankee players as Tommy Henrich and Joe DiMaggio loved big, high-pressure games like these. Henrich particularly enjoyed playing against the Brooklyn Dodgers and the Red Sox because the parks were so small that you could really see and hear the fans. Such intimacy was missing in the cathedrallike Yankee Stadium. It did not matter, Henrich thought, that the fans were rooting against you. What mattered was their passion, which was contagious to both teams. For some of the younger players, it was a bit unsettling. When Charlie Silvera, a young catcher just brought up from the minor leagues, saw the streets outside the hotel jammed with excited Boston fans, he felt like a Christian on his way to the Coliseum. Along with his buddies, Hank Bauer and Yogi Berra, he left the hotel ready to run this relatively good-natured gauntlet. The

fans crowded around to tell them that the Sox were going to get them, that Ted (Ted Williams, of course, but in conversations this intimate, he was merely Ted) was going to eat Tommy Byrne alive. It was, thought Silvera, as if nothing else in the world matters except this game.

What a glorious pennant race it was in 1948, with three teams battling almost to the last day. The Red Sox, the beloved Sox, had started slowly. They were eleven and a half games out on the last day of May. But the Boston fans did not lose faith, even if it was mixed in almost equal parts with cynicism. The Sox came back, took first place in late August, and stayed there for almost a month. Then the Cleveland Indians, with their marvelous pitching staff—including Bob Feller, the fastest pitcher in either league; Bob Lemon, judged by many hitters to be Feller’s equal; and a young rookie named Gene Bearden—made their challenge. The possibility of winning the pennant so electrified the Indians that near the end of the season Lou Boudreau, the young playing manager, had to ask the sportswriters not to come into the locker room. The players were so emotional, he said, that he feared a writer might overhear something said in anger, write it up, and an incident would be created. The writers, reflecting something about the journalistic mores of the time, all agreed.

While Boston and Cleveland battled for first, the Yankees stayed just within striking distance. All three teams set attendance records, drawing among them more than 6.5 million fans (the Indians drew 2.6 million, the Yankees 2.37, and the Red Sox, in their much smaller ball park, 1.55 million). Newspapers throughout the country headlined the pennant race every day, and in countless offices everywhere men and women brought portable radios to work—for the games were still played in the afternoon then.

The best player on each of the three teams was having a remarkable year: Joe DiMaggio of the Yankees, although

hobbled by painful leg and foot injuries, was in his last great statistical year, and was in the process of driving in 155 runs; Ted Williams of Boston ended up hitting .369 with 127 runs batted in; and Lou Boudreau of the Indians led Williams for part of the summer and ended up hitting .355, 60 points above his career average. Williams, the greatest hitter of his era, hated to be behind anyone in a batting race. While Boudreau was slightly ahead of him, the Red Sox played a doubleheader with Chicago late in the season. That day Birdie Tebbetts, the Boston catcher, needled Williams: “Looks like the Frenchman’s got you beat this year, Ted,” he said. “The hell he has,” Williams answered. He went seven for eight, with three hits to the opposite field. The last time up, with six hits already under his belt and his average having edged above Boudreau’s, he yelled to Tebbetts, “This one’s for Ted,” and hit it out.

With one week, or, more important, seven games, left in the season, the three teams were tied with identical records of 91-56. “They wanted a close race. Well, they’ve got it,” said Bucky Harris, the Yankee manager, speaking to reporters as the Yankees prepared to meet the Red Sox for a brief series in New York. “It couldn’t be any closer. But somebody has to drop tomorrow. Maybe two of us will be off the roof. But I’m not dropping my switch.”

Then the Indians moved ahead; they continued to win while the Red Sox and Yankees faltered. On Thursday the

New York Times

headline observed:

INDIANS NEAR PENNANT AS FELLER WINS.

The Indians had a two-game lead, with only three games left.

As the Yankees prepared to take on Boston at Fenway, the Indians played their last three against fifth-place Detroit. On Friday Cleveland took a 3-2 lead into the ninth inning behind Bob Lemon. But Lemon tired, and Detroit rallied to win 5-3. So the door had opened just slightly for either Boston or New York.

Fenway was one of the smallest parks in the majors and

every one of its 35,000 seats was taken on Saturday. The Boston management noted sadly that if they had had 100,000 seats they could have sold them all that day. In the first game at Fenway, the Red Sox beat the Yankees when Williams hit a long home run off Tommy Byrne. Rundown by a cold he seemed unable to shake—despite his use of penicillin, then still a miracle drug—Williams had clinched the batting title. There had been a special pleasure for Williams in getting the crucial home run off Byrne because Byrne normally tormented Williams every time he came up: “Hey, Ted, how’s the Boston press these days? Still screwing you. That’s a shame. ... I think you deserve better from them. ... By the way, what are you hitting? ... You don’t know? Goddamn, Ted, the last time I looked it up, it was three-sixty or something. Not bad for someone your age. ...” Williams, in desperation, would turn to Yogi Berra, the Yankee catcher, and say, “Yogi, can you get that crazy left-handed son of a bitch to shut up and throw the ball?”

With the victory over the Yankees, the Red Sox still were a game out of first; to win a share of the pennant they needed to beat the Yankees in the final game. That night, the DiMaggio brothers—Joe, the center fielder of the Yankees, and Dominic, the center fielder of the Red Sox—drove together to Dominic’s house in suburban Wellesley. There was to be a family dinner that night for Dominic, who was scheduled to be married on October 7. Their parents had left San Francisco for a rare trip east to attend the wedding and to see the final games of the season as well. If the Red Sox made the World Series, then the wedding would be postponed to October 17.

For a long time it was quiet in the car—Joe could be reserved even with his family and closest friends and even in the best of times. “If he said hello to you,” his contemporary Hank Greenberg once said, “that was a long conversation.” This day, when his team had been eliminated

from the pennant race, was not the best of times. Finally he turned to his younger brother and said, “You knocked us out today, but we’ll get back at you tomorrow—we’ll knock you out. I’ll take care of it personally.” Dominic pondered that for a moment. The role of being Joe DiMaggio’s younger brother had never been easy. Dominic chose his words carefully.