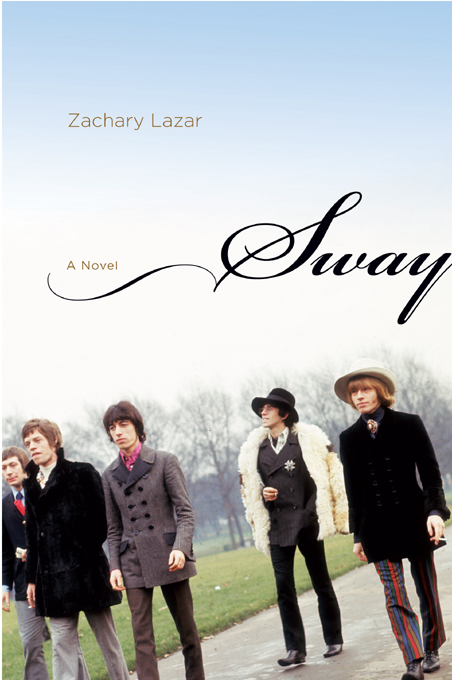

Sway

Copyright ©

2008 by Zachary Lazar

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database

or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY

10017

Visit our Web site at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: January

2008

Illustrations from the Rider-Waite Tarot Deck

® reproduced by permission of U.S. Games Systems, Inc., Stamford, CT

06902 USA. Copyright ©

1971 by U.S. Games Systems, Inc. Further reproduction prohibited. The Rider-Waite Tarot Deck

® is a registered trademark of U.S. Games Systems, Inc.

ISBN-13: 0-316-11309-3

Contents

ALSO BY ZACHARY LAZAR

Aaron, Approximately

For Sarah Lazar,

Peter Gallagher, and

Christina Carrad

Sway

is a work of fiction. Among other things, it is an examination of the way several public lives were detached from the realm

of fact and became a kind of contemporary folklore. As such, the book should not be read as a factual account of events or

as biography. While many of the characters in the novel bear the names of actual people, they and their actions have been

imagined by the author and should be considered products of the imagination.

FROM A DISTANCE,

they had the demeanor of prisoner and guard. Bobby looked down at the frayed cuffs of his shirt, pushing them back over his

wrists as he followed Charlie away from the house. His truck stood in the sun, its fender dented, the bed enclosed by weathered

wooden boards. Beside him, Charlie looked silently ahead, his hair covering his face and beard, his hands crossed behind his

back. He was an ex-convict, maybe fifteen years older than Bobby, but it was hard to think of him as being any particular

age. He had taken just one look at the beat-up piano in the back of Bobby’s truck and his face had gone expressionless, as

if it disgusted him.

“We’ll take the Ford,” he said, holding out the keys to Bobby in the flat of his palm. Then he smiled a little facetiously,

a smile at nothing, as if they both knew there were intricate layers of pretense between them and Charlie was inviting Bobby

to admit it. “Do you mind driving?” he said. “I don’t really feel like driving right now.”

There were two men coming up the road on motorcycles, some girls walking back from the corral, carrying empty buckets. Dogs

slept in the shade beneath the broken planking of a shed. It was an abandoned ranch. The first time Bobby had seen the place

he’d felt oddly protective of it because it had seemed so doomed. The buildings were falling apart — shingles missing, holes

in the walls, windows covered by black garbage bags or sometimes just left as empty frames. There were drawings everywhere

of peace signs, animals, birds. His first day there, with his girlfriend Kitty, they had all fallen in love with his teen-idol

face, his jeans with the colored velvet patches. It was like a lot of other places he’d been in the past two years — everywhere

along the coast now there were groups of young people with nowhere to go and no money to spend. It was as if they were living

in a fort or a tree house. They scraped meals together out of plants they grew or things they scavenged from the trash outside

of supermarkets.

He looked back at his truck as they got into the car. The piano was strung up with lengths of rope, a battered upright with

a few deep scratches on its side. He was a musician — that had been his plan, to be a rock musician — but it struck him now,

with Charlie there, that the plan had become unreal somehow, that it had been diminishing so slowly that he hadn’t noticed.

Two years ago, he’d starred in an avant-garde film about the rise of Lucifer, a kind of rock-and-roll god who seduced the

world not into peace and love but into something more brutal, something more like ecstasy. He’d thought of it at the time

as just a stepping-stone to other ambitions, but the role had also appealed to him, had spoken to his particular gift — “charm,”

“charisma,” none of the words captured its unpredictability, the way it was sometimes in his grasp, sometimes not.

Yesterday, in one of the barns, he’d been looking for some twine or rope to secure the piano to the back of his truck when

he’d come across a gun sitting in a tool chest, wrapped in a towel. Kitty had been with him — she was hardly even a friend

anymore, just another one of the girls he would see when he was at the ranch. She watched his expression as she pulled up

the halter strap on her shirt, her face a mocking reflection of his surprise. The gun was a revolver, the wooden grip splintered

on one side, the wood as dry and smooth as bone. When he looked back at Kitty, his head tilted a little to the side, her eyes

seemed to say,

Who do you think you are? You’re really just some good-looking fool, the kind of boy I would have had a crush on in high school

.

“Be quiet for a minute,” he said.

She looked at him, her arms crossed in front of her chest. “Cut it out, Bobby.”

“You can stop staring at me like that. I know what you were thinking just now.”

He brought his hand to the back of her neck and tried to kiss her. She turned her head away at first, but he turned it back,

his fingers on her jaw. His chest was heavy, his face unsmiling. He moved away from her a step, letting his hand slide from

her neck down her back, the gun still in his other hand, pressing against her arm. Her hair was sheared off at different lengths,

standing up in clumps. She was so small, so delicate, that he was almost afraid, his hand on her back, feeling the flat muscles

beneath her shirt. She kept her eyes open, watching him, as he backed her toward the table behind her, propping her up a little

in his arms. He just stood there for a while, close enough to brush his body against hers, to feel the rise of her breasts

against his rib cage. Then he unbuttoned the front of her jeans, using just one hand, the other one still on the gun.

“You know, you’ve been here so long you can’t even remember your own name anymore,” he said. “I thought you were a little

smarter than that.”

“I don’t really care what you think.”

“All this ‘Charlie is Christ’ bullshit. Or is it ‘Charlie’s the Devil’? I forget.”

“My parents were strange people,” she said, leaning back, her hand on the table. “They never really talked. They just sort

of policed each other. I never understood what they were so afraid of. What are you so afraid of?”

The words and ideas were not exactly hers. She had become smarter than before, but also dreamier, smarter but also absent.

He thought of the first time he’d seen her walk off with Charlie, maybe a month or two ago, her hand in the back of his jeans,

sloppy and blatant and stoned. “Turning them out,” Charlie called it, “breaking them in.” If you seduced them like a father

with his daughter, if you scared them a little, got inside their heads, then any kindness you did them afterward would seem

like an act of God.

He pushed his fingers down through the opening of Kitty’s fly, feeling the rise of muscle beneath the tangled wedge of hair.

She looked right into his eyes and seemed to barely see him.

This morning, he’d found her in the kitchen, washing dishes in the ragged slip she sometimes wore as a dress, her nose and

the skin around her mouth burned red by the sun. She was all forearms and shins, barefoot on the dirty kitchen floor, even

smaller than he’d remembered.

“You just need to leave me alone for a little while,” she’d said.

He thought of her hips rising toward him in the barn, the freckles on her rib cage reminding him somehow that she was sixteen,

a girl from a house with a swimming pool in Brentwood. He told her that he was going to take the used piano over to his friend

Gary’s place, pick up the twenty dollars profit, use the money to buy some motorcycle parts. He asked her if she wanted to

come along. He spoke in a purposeful voice, as if nothing had happened between them, but she just smiled at him in a disbelieving

way, as if she knew that Charlie was about to walk in and say that he and Bobby needed to go have a talk.

He got in the Ford with Charlie and they headed south toward Los Angeles, listening to a faint scratch of music on the radio,

not speaking. The rocks outside were gray, the plants a grayish green, the dirt tan. Everything was the color of dust, except

the sky, which was a washed-out blue behind a thin yellow haze. At the little store outside of Chatsworth, they pulled over

and Charlie bought a six-pack of beer and some things for the girls: a booklet of find-the-word puzzles, some candy bars.

Bobby started the car and backed up, looking over his shoulder. When they got on the highway, Charlie lit a joint, examining

its smoke as it leached out the cracked window. He passed it over, his hand low, down by Bobby’s knee.

“You’re kind of quiet,” he said.

“I’m not quiet, I’m just wondering where we’re going.”

“We’re going to a friend of mine’s house. It’s nice there, peaceful. You’ll like it.”

They were on Highway 118, heading toward Topanga Canyon. They drove for a while, looking at the sparse houses surrounded by

trees — oaks, sycamores, a few tall eucalyptuses. After the hills, they came eventually into the suburbs: gas stations, coffee

shops, a movie theater.

“I always thought you were a nice kid,” Charlie said. “But I guess maybe there’s more to you than that. Like maybe you weren’t

just bullshitting me about the time you spent in that reform school, for example.”

Bobby looked ahead at the road. “This is about Kitty, isn’t it?” he said. “Whatever Kitty told you.”

“What does that mean?”

“This little talk we’re having. Whatever this is. She knew about this.”

Charlie looked down at his lap, rubbing his knees with his hands. “You need to stop thinking so much,” he said. He brushed

something off the dashboard with the side of his hand. “Turn up here,” he said. “Take a left.”

“Left?”

“Up here at the light. Put your signal on.”

Bobby turned from the wide boulevard onto a two-lane street, steering with one hand, the other on the vinyl armrest between

them. They passed a Safeway supermarket on the corner, then a post office and a school, then they were in an ordinary neighborhood

of small houses behind sidewalks and fences.

“That piano you had in your truck back there,” Charlie said. “I was just wondering, where were you taking that thing?”

Bobby looked at him blankly, not even understanding for a moment. “What?”

“That piano you had in your truck. I was wondering where were you taking it.”

“I was taking it to Gary Hinman’s. He’s buying it from me. I got it cheap at one of the auctions.”

“Yeah, well, I figured something like that. I was just wondering where you got that piece of shit in the first place. I wanted

to make sure you didn’t find that on the ranch somewhere.”

“I bought it at an auction.”

“That’s what you said.”

“Yeah. That’s what I said. What is this?”

Charlie stared at him with an expectant frown, as if waiting for more. Then he turned away, and Bobby wished he had never

seen the piano, or that he had found it on the ranch, that he had stolen it.

“I just wonder what goes on in that head of yours sometimes,” Charlie said. “Selling a used piano like that. Wasting your

time.”

Bobby turned the knob on the radio. “I’m trying to make some money.”

“Yeah, well, money. There’s lots of ways to make money.” He passed the joint, not looking at Bobby. “What day is it today?”

he said. “Friday?”

“I think it’s Thursday.”

“Not bad. Just driving around on a Thursday, getting high. Why don’t you just cool off and relax?” Charlie nodded then, his

mouth half-open, drifting into some sort of sarcastic daydream. He had a way of miming his emotions, acting them out so that

they came across as artificial and sincere at the same time. It was the way he played his guitar, dipping and bucking his

head, giving himself up to the song, but also making fun of the idea of giving himself up to the song, making fun of you for

believing it.

They drove on in silence. It was like this sometimes when you were Bobby. The way he looked — the fact that he was good-looking

— made it hard for people like Charlie to believe that he really was who he was. They were always giving him nicknames — B.B.,

Cupid, Bummer — as if “Bobby” was too intimate, as if saying it was like kissing him on the lips. He remembered being out

in the desert one time, just he and Charlie riding around in one of the jeeps, when Charlie had spiraled off into one of his

moods, suddenly angry, hectoring and strange. The world was always at war, he’d said. It wasn’t just Vietnam, it was the nature

of people, the way they made sense of things. Look at a newspaper and all you’d see were soldiers, riots, assassinations.

You’d see things being pulled apart, sides forming, rifts widening: black and white, rich and poor, young and old. It was

like everyone had looked down and finally seen that they were standing on a tightrope. They didn’t know which way to walk

(that was the problem), they didn’t know how to choose. Some of them were so scared that they just wanted to fall off. They

might seem harmless, but you had to be vigilant, because they wanted you to fall with them — that was the peculiar thing about

their fear.

Bobby was usually embarrassed when Charlie talked this way. It seemed involuntary, a way of showing too much of his hand.

They turned at the next stop sign. The house on the corner was invisible behind its high brown fence, garbage pails in front,

thick tufts of palm trees pushing out over the wooden slats.

“That’s it up there,” said Charlie. “Park up there a little ways.”

He raised his chin at one of the houses across the street. It was a Mexican-style bungalow with a carport off to one side,

a front yard covered in smoothly raked gravel. There were cactuses and yuccas planted in little islands behind white bricks.

It was so neat that it looked almost like an old toy that had been pressed into service as something real.

“I don’t think anyone’s home yet,” Charlie said. “Why don’t you let me have the keys.”

Bobby looked at him skeptically. Then he handed him the keys and Charlie nodded, clasping them in his hand.

“Just wait here for a minute,” Charlie said. “I’ll go and see if anyone’s there.”

He got out of the car and crossed the street, heading up the sidewalk that bordered the gravel yard. He had the sack of beer

cradled in one arm, his free arm dangling at his side like a little boy’s. Bobby watched him walk around to the side of the

house, following a winding path of concrete disks. Then he disappeared around the back, his head down.

Bobby wiped his eyes. He looked through the windows at the houses: ranch houses, Spanish houses, a miniature Tudor house with

a lawn and a chain-link fence. The neighborhood seemed empty, abandoned for the day of work and school. It was like the neighborhood

he’d grown up in: middle-class, somehow accidental. There were sidewalks, but nobody outside to walk on them.

He thought of Kitty, the way she had leaned her head on her shoulder last night, looking down at Charlie’s hand on her wrist,

then back up at Bobby, her eyes sleepy, dismissive. Maybe she was just acting a part — you would see it happen around Charlie

sometimes, a certain carelessness in people’s faces, a faint edge of sarcasm. Bobby had just kept talking — he’d been acting

a little like Charlie himself, he realized now — staring at Charlie to show how little it mattered: he could have Kitty back,

she was Charlie’s girl now, there were others. But the more he thought about it now, the more distorted the memory became,

his face not calm but twitching a little at the cheeks, like a rabbit’s.