Tailor of Inverness, The (19 page)

Read Tailor of Inverness, The Online

Authors: Matthew Zajac

The houses of Gnilowody are spread over an area of roughly one kilometre by 500 metres, bisected by the stream and its ponds. The houses lie on natural terraces above the waters. They are square and usually single-storeyed, with typically blue paintwork, sometimes with stencilled decorative patterns around windows and cornerstones. It is a fertile place, teeming with ducks, geese and hens, fruit trees and vegetable gardens. We walk down from the cemetery and stop outside one of the houses. âThis is where your family lived. Their house isn't here any more. This one was built maybe 30 years ago.'

I look at the replacement and try to see its predecessor. I only find the deep sense of absence which had first gripped me in the cemetery. I feel as if I am trying to pull myself out of a vacuum. I look across to the other side of the water, at the view my father would have seen every day when he looked out of his front window, at the places where he would have jumped across the stream and played, at the trees by the nearby pond. I imagine him running about in his shirt and shorts on a warm summer's day with Kazik and wee Adam trying to keep up, breaking branches to make fishing rods or bows and arrows, tormenting the fowl, throwing stones at a floating target. I remember his stories of making dominoes and

explosions

, of the village idiot and Wawolka the storyteller spae wife. Once upon a time those stories were real, they lived here.

Milanja has been told by her mother that there are a couple of old women in the village who knew my father's family quite well. As she leads us through the village, she makes enquiries of the older men and women we meet as she isn't sure exactly who or where these old women are. Eventually, we arrive on the other side of the water at the house of one of them, Olga Kindzierska. Her husband comes out to talk to us, a boyish, rosy-cheeked old man whose mind is wandering a little. He is friendly, but his memory has gone. He ushers us towards the house and we walk into the muddy yard, scattering the chickens. A lean-to protects a large stack of hay from the rain. He calls for Olga at the door and she comes out of the house.

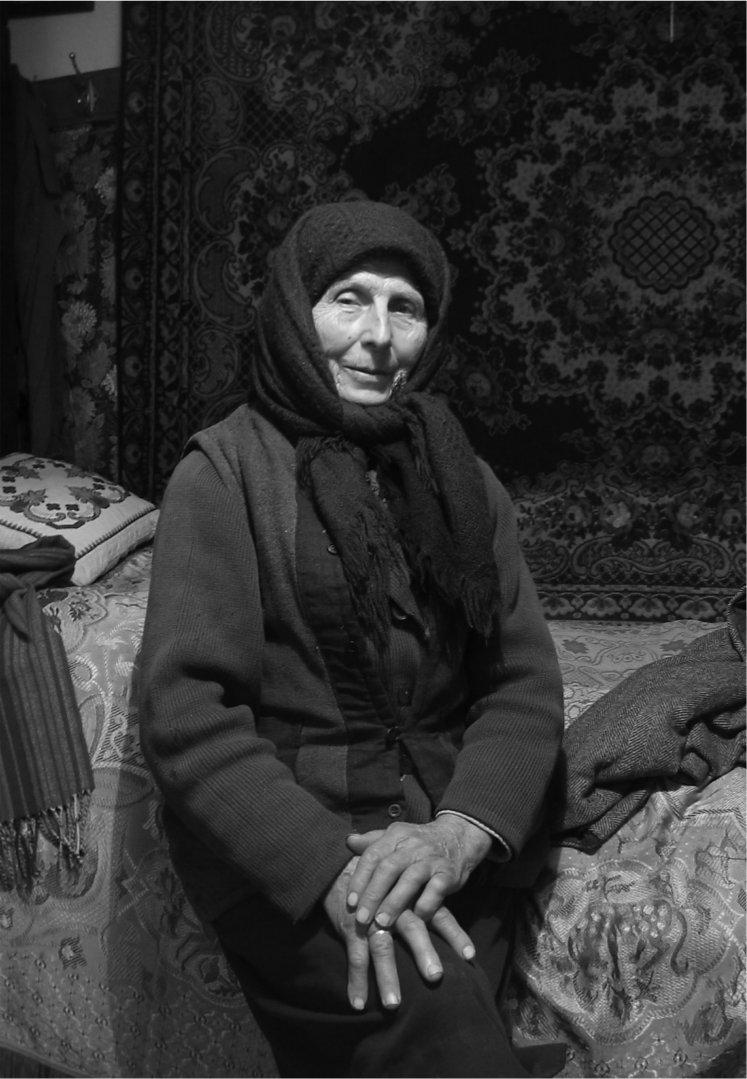

She is a thin, gentle old peasant lady with delicate features. Quite beautiful. Her face is tanned and weather-beaten, with high cheekbones and forehead, a small mouth, an aquiline nose and clear, pale blue eyes. Her hands tell of a lifetime of work on the land. Her voice is high-pitched and soft. Born in 1925, she is 77 years old and has all her wits about her. At once, an animated conversation takes place. I switch on my tape recorder.

âThe Zajac family? Which Zajac family? Ah-ha, yes, of course I remember them. And this is Kazik's son? No, Mateusz's son, I see. From Scotland? Mateusz lived there after the war? Ah-ha. And Kazik did too?' She looks at me with wonderment, smiling, remembering her youth. âYou look like your father, I can see it. He was very handsome! And you've come back.'

I've come back, to a place I've never been to before.

Olga Kindzierska 2003

Then she starts talking as if her childhood recollections are of recent events, which, in the minds of the old, is what they can seem like, and which, in the scale of time, they are.

‘Yes. There was Kazik and Mateusz and Milanja and Adam. Their parents were good people. Very important in the village. They had the biggest farm. About 40 hectares, many cows and horses. I went to school with Adam.’ She laughs when she recalls Adam. ‘He was always getting up to something. Practical jokes. Pulling the girls’ pigtails in class, emptying the teacher’s inkwell, tying a tin can to the back of someone’s cart. He was a wild one, but very popular. I didn’t know Mateusz so well. I think he must have started his tailoring work when I was about 10 or 11, he was 5 or 6 years older than me. And Kazik was a very kind man, and respected by everyone. He was a civil servant and then he was an officer in the Polish Army. There was a horse which went wild once. It kicked me and knocked me out. I was lying there in the field and the horse could have trampled me. But Kazik caught that horse and calmed it down, so he saved me. He always brought flowers for his mother when he visited. I remember he promised that he would bring seeds and plant flowers for me. But then the Russians came.

‘And then, of course, there was the scandal in the village, when your father got a girl pregnant. And he said the baby wasn’t his, but it was his and his parents and the elders discussed the matter and the result was they said he must marry her. And so there was a wedding, a short wedding. It was 1940. And a few months later, the baby was born, a little girl.’

I’m standing in front of her holding my microphone as the tape runs. Lesia translates Olga’s words for me. Lesia, Olga, Bogdan, Taras and the accompanying villagers all seem to be watching me, waiting for my response. Or at least, that’s what it feels like, as time seems to slow down and stretch for this moment as I absorb what she is telling me.

So this is why I have come. This is the purpose of my visit. It has all been leading to this moment. A wave of mild nausea overtakes me, I am mentally winded, my brain seems to

simultaneously

empty itself of everything and fill itself with the image of Olga’s mouth uttering her revelation and what I can only inadequately describe as the essence of my relationship with my father. The sound of his voice, his smiling eyes, his big gentle hands, his slick-backed hair, the tweeds, threads and cloths which surrounded him, his drive, always forward. After a few seconds, I answer, automatically.

‘Right…and…and what was the woman’s name?’

Olga realises that this is new information to me. There is a look of compassion and perhaps mild alarm in her eyes.

‘Laska, Anna Laska.’

‘Anna Laska. Right…and what was the baby’s name?’

‘I think it was Irka, no? Yes, Irka, Irena. Irena.’

‘Irena.’

I nod and smile weakly, trying to absorb what Olga has just told me. There is a silence. I am breathing quite hard and I think I have turned a little pale. Lesia intervenes.

‘Are you all right Matthew?’

‘Yes, don’t worry, I’m OK.’ I gather myself. Olga carries on.

‘After the wedding, your father lived with Anna and her parents and worked in Pidhaitsi. And then he was taken away by the Russian Army. Your grandparents loved the baby very much. Sometimes she would stay with them when Anna had to work in the fields. Your grandmother was very kind to her.’

‘So where are Anna and Irena now?’

‘I don’t know. Nearly all the Poles left here in 1945. Not all of them. My husband is Polish. And there are still one or two relatives of Anna Laska’s here. You could ask them.’ She gives Lesia and Bogdan directions. I press Olga’s hands to mine, thanking her as I am led away. She smiles at me kindly and wishes me well.

Thoughts race through my mind. I have a half sister. She’s called Irena. She must be 62 or 63. My parents didn’t marry until 1955 even though they’d been together since 1948. They were always very secretive about the date of their marriage. It only came out when my oldest sister needed her birth certificate to get a passport in the late ‘60s. That must be why they didn’t marry until then, because he was already married when they met. They always insisted that it was to do with him losing his papers during the war. I remembered my Scottish granny telling me how they had eloped, with my father turning up at her door several weeks later to announce that they had got married in secret. Secrets. It was all too clear to me now that my father had lived with many secrets until he died. My mother was still living with them.

We walk to another part of the village. Families are working in their gardens and we stop by one of them and a man in his sixties greets us. Yes, he knew Anna Laska, he was her cousin, Zinoviy Buhaj. Buhaj. My father’s cousin in New York State was Anna Buhaj. The same explanations of who we are and why we are there ensue. A neat, fresh-faced woman in a black scarf comes forward, Zinoviy’s daughter Olga Zenov. They tell us that Anna and Irena had visited Gnilowody three times, the last time a few years ago. They had received a letter from Poland a month ago which said that Anna was ill, that she couldn’t walk. Olga thinks that Irena is living in France, married to a rich businessman. She smiles at me. Yes, she has an address for Anna, but it is at her apartment in Ternopil. Lesia takes her details and we arrange to visit her in a couple of days.

We drive back to Pidhaitsi. There is a subdued atmosphere in the car.

‘Well, I didn’t expect that.’

Lesia smiles. ‘You see, life was very hard then for everyone. A lot of bad things happened. And your father never told you about any of this?’

‘No. Nothing.’

‘These times were very painful. Your father was just trying to survive them like everyone else.’

‘I know.’

I sit in Bogdan and Hala’s living room in the morning. Bogdan switches on the radio before going to the post office. The radio is always tuned to the live broadcast from the Ukrainian Rada (parliament) in Kyiv. At this time of day, haranguing speeches are made. After each portentous statement, which seems to last about 15 seconds, there’s a pause, then a declining octave of electronic notes plays at a ponderous pace. This goes on for a good hour. Clearly, it’s a regular procedure, this chant of the lawmakers, but it mystifies me.

I finish my diary entry for the previous day, the day of revelation, and speculate about Irena. Is she alive? Is Anna alive? Anna. She has the same Christian name as my mother. Is that simply a coincidence? Or did my father see something of his first wife in his second? Did he see the second Anna as a sign of some kind of salvation after his years of fear and hardship? I will never know the answers to these questions and really, they don’t matter. What’s done is done. He was a loving husband and his love for my mother was fully

reciprocated

. They both looked forward.

The fact of Irena’s existence has overwhelmed me so much, that I had almost forgotten another startling story told to me

on my visit to Gnilowody. I can’t even remember who told it, whether the teller was a man or a woman. It was certainly one of the old folk we had met on our pilgrimage round the village. The day had been so dream-like I almost doubted that I had heard it, but it was there in my head and I did not invent it.

When my father was conscripted by the Soviets in 1940, there were two or three other young men from the village who were taken with him. One of them returned several years after the war had ended. He had been taken prisoner by the Germans in 1941. With repatriation, he suffered the fate of virtually all Soviet survivors of the German labour camps, another prison sentence, in a Soviet labour camp, years in the Gulag branded as a coward or a collaborator. This was official policy. This man, whose name I wasn’t told, had been in my father’s unit.

Not long after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, they were captured and deposited in one of the hundreds of makeshift prison camps the Germans set up. Their invasion had been much more successful than they had anticipated. The Soviets were completely unprepared for it and as a result, over one million Soviet soldiers were captured within a month. The Germans were also completely unprepared for such a huge quantity of prisoners. Not that the Nazi command cared. Most of their prison camps were no more than open fields surrounded by barbed wire and guards, with no shelter, no toilets and worst of all, no food. Hundreds of thousands of these prisoners died of starvation.

The last the returning man had seen of my father was in one of these camps. He was starving, at death’s door and the man thought he must have died too. As we know, he didn’t. Some time in autumn ’41, the Nazi command decided that they were wasting a good source of slave labour by allowing these prisoners to die, so they began to feed them and set them to work. I had known that my father suffered starvation in

the war. He once told me about eating seagulls in Italy and Kazik’s wife Alice had told me that when she first met my father after his arrival in Glasgow, she had found him more than once in her kitchen wolfing down a whole jar of jam. He always ate quickly and wouldn’t tolerate his children leaving anything on their plate.

I leave these thoughts and walk through Pidhaitsi to Lesia’s school. I have agreed to give a talk to her English students. So I spend an hour with around 50 Ukrainian young people, aged between 11 and 18, telling them about Scotland, the UK, the Queen and life as an actor. I sing them ‘Wild Mountain Thyme’ and answer their numerous questions. Their English is excellent and their questions intelligent, even from the 11-year-olds. I think that here lies the hope of Ukraine.

It’s a misty morning when we leave Pidhaitsi, heading for Ternopil. Lesia’s brother, Hrihoriy, has organised our transport, with a friendly local driver named Levko. The sun breaks through during the journey as we drive through the vast expanse of arable land, the endless Ukrainian fields, masked at times by screens of trees, the sunlight flickering through their yellow leaves. I have four things to do on this day: get the address of my father’s first wife; visit Mykola and Xenia; do some shopping; meet Roman and take copies of his immigration information as I’ve offered to write to the Queen on his behalf!

We arrive in Ternopil mid-morning, stopping first at the huge market by the bus station, a warren of covered stalls, prefabricated box-like shop units and larger stores. Lesia wants to buy light bulbs and we stop at an electrical stall. It turns out that she knows the stallholder. He’s a friend of a journalist who was recently murdered in Kyiv, at the behest of President Kuczma some allege. The journalist was from this region, a nationalist sympathiser. The stallholder has photographs of his funeral, held in his home village. There are hundreds of

mourners in a long procession led by priests and others carrying religious banners.

We drive into the city centre, where I buy carved wooden plates, a few boxes of chocolates and CDs for my daughters, Sugababes, Dido, Avril Lavigne and some Ukrainian music recommended by Lesia. Then off to a suburb, searching for the home of Olga Zenov, the relative of Anna Laska, whom we’d met in Gnilowody. Her apartment is in a large block, one of several in another Soviet scheme. When she opens the door to her flat, I don’t recognise Olga at once. In Gnilowody, she’d worn a black headscarf which had covered her hair. Now her head is uncovered and her hair is not black, as I had expected, but completely, prematurely grey. Inside, her flat is tidy, clean and comfortable, decorated and furnished with the now-familiar tapestry hangings, white lace, net curtains and dark wooden chests and display cabinets.

We don’t stay long. We take the details of Anna Laska’s address. She has married again and is now called Kotek. She and her husband Jan are living in a Polish town called Mieszkowice. Olga wishes us luck. I thank her and we smile warmly at each other. She’s reluctant to accept a box of chocolates. She protests that she has done nothing to deserve them.

We find Levko parked across the wide boulevard opposite a line of street traders, some working out of vans and small trucks, others sitting on stools with their goods spread out in front of them on crates, rugs or simply the grass: shoes,

vegetables

, toiletries, second-hand clothes and electrical goods, eggs, chickens, preserves and pickles.

Lesia has expressed some scepticism about the value of a second visit to see Mykola and Xenia, influenced, I expect, by Bogdan. She is disappointed by the brevity of Mykola’s written account of his memories of my father and believes he has little more to tell us. I’m not concerned about this as I’m keen to

see them again, irrespective of what I might or might not find out. They’re pleased to see me, though Xenia seems tired or disappointed, I can’t work out which. Is it the effort required to entertain me again, or that I haven’t visited enough. She’d expressed bitterness towards Bogdan on my first visit, complaining that when an American cousin had visited, a member of the family whose grave we had visited in Pidhaitsi on my first day there, Bogdan had snaffled the greater portion of the dollars he’d left for them. Mykola, on the other hand, is even-tempered, never wavering from the smiling, rather dignified, warm and amused demeanour he’d first met me with at the railway station.

After ten minutes or so, Xenia’s mood lightens. At first, I’d thought it best not to stay too long, but now Xenia has roused herself into the hospitable old lady she is, applying herself to the task of providing us with lunch. When she hears that Levko is downstairs, waiting in the car, she urges us to fetch him, which I do. We sit down and eat delicious

plov

, along with the usual spread of cold meats, salads, pickle and bread and Mykola’s excellent

samohon

(home-made vodka). I switch on the tape recorder and we go through the story once more.

This time, Mykola states that Pavlo, my aunt Milanja’s husband, had also told him of my father’s visit to Gnilowody in 1944, that Pavlo had seen him. But we had found no living witness to this in Gnilowody. Mykola knows about Anna Laska and the child Irena. He describes my father as an

intelligent

man who always thought before he spoke when Mykola probed him about his wartime experience at their 1982 meeting. His probing didn’t appear to reveal any more than what Mykola had already told me. He says that my father preferred to change the subject, that he avoided going too deeply into details.

We talk about the Polish-Ukrainian conflict. Xenia asserts that there was none of this in Gnilowody and Mozoliwka. I

was to discover later that this was not true. Xenia’s own village, to the east of Pidhaitsi, experienced it. Her father, a Ukrainian, had hidden his Polish friends in his cellar. It was these Poles who she and Mykola were visiting in Zielona Gora in 1982.

Mykola’s brother Teodosiy had spent 25 years as a prisoner in Siberia for his membership of the SS Halychyna Division. He had worked in a power plant there for most of his sentence. When he was finally released, he was forbidden from living in his home region, so he settled in Chernivtsi, 200km

south-east

of Ternopil. I was to discover later that Mykola had also been in the Halychyna Division. I was told that he had escaped the wrath of the Soviet authorities through the efforts of his first wife, a party member whom he had married shortly after the war ended.

Again, our time is too short. I’ve arranged a meeting with Roman at 2.30. I am already late. Xenia produces a stack of chocolate bars and a wonderfully kitsch tapestry picture of two grey and black kittens on a sky blue background, which she has made since our last meeting and sewn on to a square of pale green satin to make a cushion cover. She also gives me a little icon of the Virgin Mary for luck and to protect me from evil. Mykola presents me with a bottle of his five-year-old

samohon

. He then goes to his little greenhouse on the verandah and picks the single, perfect lemon which hangs from his tree. He gives it to Lesia, who is delighted. Xenia urges me to return, calling me a ‘fine boy’. We hug and kiss, look into each other’s eyes, and part.

I see Roman from a distance, standing in the square in front of the theatre with the actor Yuri. He hands me a sheaf of papers: copies of a letter from the Canadian Embassy in Kyiv rejecting his application for residency, his marriage certificate, a letter from his wife and a testimonial from a Canadian woman he’d worked for. I will use these for the letter I’ll write to the Queen on his behalf. Mychaylo wants to see me, so we

go to his office in the theatre. He wants to know more about me, about my response to the festival and about what possibilities there are for future co-operation. He tells me that the next time he sees me it will be on a stage. We discuss the anti-semitism issue and he offers the apologia offered by others. ‘You must understand this is our history, these social relations, but we’re not anti-semitic now.’ I’d raised this with five or six people during the course of my stay. Usually I was met with a degree of amusement and the inference that I was taking it all too seriously, that it was just a joke, a reflection of the past. One person seemed offended, not because I was suggesting she was anti-semitic, but because I had failed to grasp that an anti-semitic attitude was only logical, even natural for a Ukrainian in the light of history and contemporary politics in the country.

I explain to Mychaylo that although I admire his company’s production of the Staritsky play and that I believe it would stand up well against the work of the best companies in Britain, the play’s casual anti-semitism would be unacceptable there. I welcome the opportunity to be frank with him in the sober atmosphere of an ordinary working day. He is clearly

recovering

from the intensity of the festival. As the lynchpin of the event, the Schevchenko Theatre’s dynamo, I have developed an admiration for Mychaylo. He has a strong desire for

recognition

, not for himself, but for his company’s work, which he sees as part of the Ukrainian renaissance taking place as Ukraine realises its independence. I hope he gets it and along with it, over time, a shedding of the brutalised mentality which still afflicts many people in Eastern Europe, the combination of naivety, lack of sophistication, xenophobia and venality produced by a history of physical hardship, subjugation and terror.

I take Roman and Yuri for a beer outside the Café Europe for my last hour in Ternopil. I wonder if Roman will see

Canada again. I gaze once more with grateful astonishment as one statuesque beauty after another passes by. The three of us don’t say much, subdued by the impending farewell. Roman and Yuri hope I’ll return. I say that when I do, I hope Roman won’t be here.

I spend the evening eating and drinking with Bogdan and Hala and their friends Miroslav and Ola, Lesia’s parents. Later, Hala shows me the Baldys family tree, starting at Bogdan’s grandparents, my great-grandparents Gerasimus and Karolina. They had 8 children, 4 girls and 4 boys, including my

grandmother

Zofia.

Hala asks me if I want to wash my feet. She provides a basin of hot water and pulls down the loo seat for me to sit on. She scrubs my socks while I wash my feet and then brush my teeth. Its strange and touching to share such intimacy when we’ve known each other for only four days, but Hala is a practical woman and now I’m family. My employment of Levko as a driver proves to be a sore point with Bogdan. He is angry that this was arranged without his knowledge. He would have asked Taras to do it, thus fulfilling his familial duty to me and also keeping my money in the family.

Lying in the fold-down bed settee as Pidhaitsi’s dogs howl in the night, I dream that my grandfather is not, in fact, a Pole, but an Iraqi related to Saddam Hussein! I’ve seen only one photograph of him, towards the end of his life, thin-faced and staring, with a thick, Saddam-like moustache. There is a voice in the dream telling me this, whose I don’t know. It’s a comical suggestion, one which mocks my search for

information

. But in a way, it’s also pertinent. His identity, and that of so many of the dead, particularly here where so many have died in the chaos of war, is buried. Yes, he was a Pole, a rich farmer from Gnilowody, son of an earlier Mateusz, but for me now, that’s as far as it goes. For all I know, he could have been a relative of Saddam, Queen Victoria, Charlie Chaplin

or anyone else you care to mention. Is there a point where the extended branches of a family tree become meaningless? Or is the real meaning of ancestry the fact that each of us is ultimately connected with every other human being?