Tainaron: Mail From Another City (19 page)

Read Tainaron: Mail From Another City Online

Authors: Leena Krohn

Tags: #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Fantasy, #Myths & Legends, #Norse & Viking, #Literature & Fiction, #Contemporary Fiction

456

'Is there a storm brewing?' I asked.

457

'It is not a storm,' he said. 'Worse. It is winter. Although it will be a long time before it reaches us. But when it is here, I pity those who have not already gone to sleep!'

458

I already felt cold now, in full sunlight. We looked in silence at the majestic shape of snow and ice. To me it still did not look as if it were changing shape or approaching Tainaron.

459

'Perhaps it will not come this time, after all,' I said to Longhorn, half in earnest, and hopeful. 'Perhaps it will stay up there in the north.'

460

'What a child it is,' Longhorn said in an aside, as if there had been a third person with us on the platform. Then he continued, turning to me once more: 'I did not bring you here only to look at the coming of winter. Do you see?'

461

Longhorn gestured toward the northern edge of the city, below the winter, where there swelled a cluster of dwellings of different heights and shapes. It must have been because of my sore eyes that their outlines looked so indefinite. As we looked, it seemed strangely as if some of them were in motion.

462

'What is happening there?' I asked.

463

'Changes,' he said.

464

That was indeed how it looked. Clouds of dust spread on the plain - and in a moment all that could be seen where the crenellations of towers and blocks had meandered were mere ruins. But there had been no sound of any explosion.

465

'That part of the city no longer exists,' he said calmly.

466

'Not an earthquake, surely?' I asked fearfully, although I could not yet feel any tremors.

467

'No, they are merely demolishing the former Tainaron,' Longhorn said.

468

Longhorn raised his finger and pointed westward. And there, too, I saw demolition work, destruction, collapse, landslides. But almost at the same time, in place of the former constructions, new forms began to appear, softly curving mall complexes, flights of stairs that still ended in air, solitary spiral towers and colonnades which progressed meanderingly toward the empty shore.

469

'But...' I began.

470

'Shh,' Longhorn said. 'Look over there.'

471

I looked. There, where a straight boulevard had run a moment ago, narrow paths now wandered. Their network branched over a larger and larger area before my very eyes.

472

'And this goes on all the time, incessantly,' he said. 'Tainaron is not a place, as you perhaps think. It is an event which no one measures. It is no use anyone trying to make maps. It would be a waste of time and effort. Do you understand now?'

473

I could not deny that I understood that Tainaron lived in the same way as many of its inhabitants; it too was a creature that was shaped by irresistible forces. Now I also understood that I should never again taste those smoke-scented wafers which I had wanted so much this morning. And yet I understood very little.

474

'I am thirsty,' I said to Longhorn, longing once more for the foam of dayma.

475

476

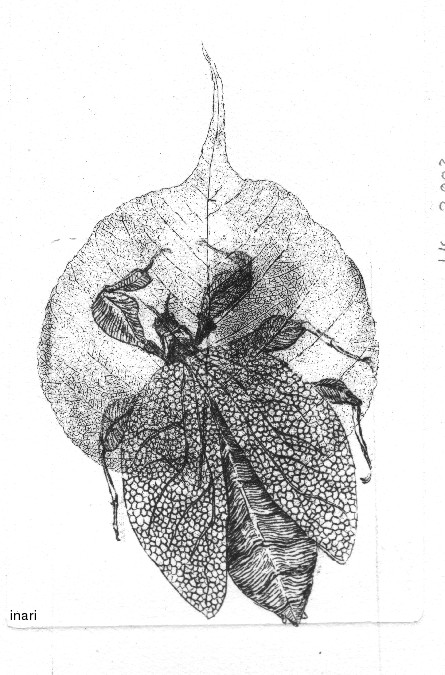

The Dangler - the twenty-third letter

477

I really must say that many of the inhabitants of Tainaron have the most extraordinary habits, at least to the eyes of one who has come from so far away. Quite close to here, in the same block, lives a gentleman, tall and thin, who is in the habit of hanging upside-down from his balcony for a number of hours every day. This strange position does not seem to interest passers-by in the least, but when I passed under him for the first time I was so startled that I immediately thought of running for help. I thought, you see, that there had been an accident and that the man was clinging to the wrought-iron decorations of the balcony with his feet. Longhorn, who was beside me, remarked coolly that he had selected his pose through his own free choice and that I would be wise not to interfere so eagerly in other people's lives. I admit that I was offended by his remark, but recently I have begun meekly to take his advice.

478

I see the man most days, and whenever I walk under his balcony I greet him, even though he never responds. In fact, I think he is either asleep or meditating. In his chosen state he is so limp and floating that he recalls a garment that a washerwoman has hung out to dry. With incomparable calm he suspends his head above the busy street without stirring, even when the fire brigade drives under him, sirens wailing. He always looks the same: a bright, even gaudy, green, so that one can make him out from the broad steps of the bank at the end of the state like a living leaf against a red brick wall...

479

Does he dream as he hangs there, sometimes suspended from just one limb, but nevertheless apparently completely relaxed? I believe that is exactly how it is. I know from my own experience the difference between the immobility of fear and the immobility of the hunter, but this is neither. I believe he dreams, dreams swiftly, passionately and incessantly, dreams with death-defying intensity without sacrificing even a jot of consciousness to the struggles of everyday waking life. I believe he must long ago become convinced that all action is unnecessary, or even dangerous.

480

There are days when I think that this gentleman is admirable and his way of spending moments of his life most enviable. On such days I, too, would like to concentrate on sweet communion with my private visions as headlong and with the same kind of mental calm as he. But do not imagine that it would be possible. In the evenings, even if I shut my window tightly, turn out my lamp and fill my ears with cotton-wool, this city teems before me, still more restless and colourful than in full daylight. Then I should like to get up and got to see whether the green gentleman is still hanging head-first from his balcony. I should like to climb up there myself and position my limbs just like his. Then, with my blood flooding my head, all of Tainaron would begin to dissolve into the mists and I, too, should begin a dream, endless and leaf-green....

481

But if, in the morning, my nocturnal experiences return to mind, if I have idled through agonising labyrinths, I know that I would not wish to spend my life in the city of dreams. If, on such a morning, I pass under the Dangler's balcony, I am more inclined to pity him than to admire him.

482

Other books

Hand of Fate by Lis Wiehl

Hot SEALs: Through Her Eyes by Delilah Devlin

Claimed: Death Dealers MC Book 3 by Sapphire, Alana

Brandenburg by Porter, Henry

El Inca by Alberto Vázquez-Figueroa

A McCree Christmas (Chasing McCree) by Isabella, J.C.

Sovereign of the Seven Isles 7: Reishi Adept by David A. Wells

Dead Spaces: The Big Uneasy 2.0 by Pauline Baird Jones

The 4 Phase Man by Richard Steinberg