Take Six Girls: The Lives of the Mitford Sisters (51 page)

Read Take Six Girls: The Lives of the Mitford Sisters Online

Authors: Laura Thompson

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical

Unity in 1940, after her suicide attempt, being transported on a stretcher from the port of Folkestone to her home in High Wycombe. Her father (

extreme right

) looks on.

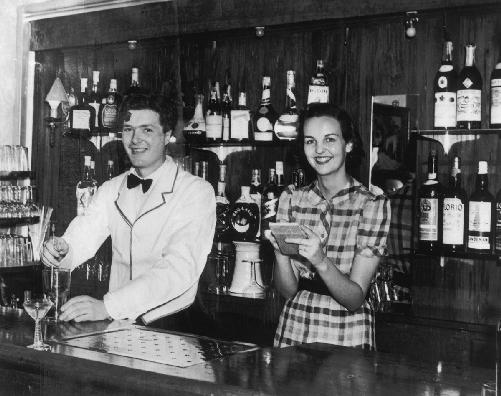

Jessica in 1940 with her first husband, Esmond Romilly. The couple briefly ran a bar in Miami.

Deborah’s wedding day in 1941. She was dressed by Victor Stiebel; her father wore his Home Guard uniform.

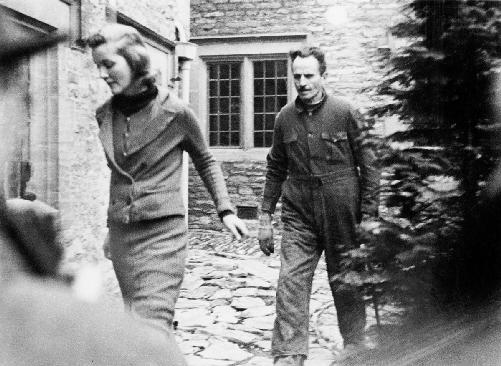

Diana and her second husband, Sir Oswald Mosley, under house arrest after their release from Holloway in late 1943.

The Mill Cottage at Swinbrook, formerly owned by David, later rented by Sydney as a place of refuge for Unity.

Nancy in the 1950s, at her beloved apartment in the Rue Monsieur, holding one of her writing notebooks.

The young Duchess of Devonshire: Deborah in 1954.

Jessica in 1966 with her second husband, Robert Treuhaft.

The graves of Nancy, Unity and Diana in the churchyard of St Mary’s, Swinbrook. Diana’s grandson Alexander, who died in 2009, is buried to her left.

The Mitford children in 1935, with members of the Heythrop hunt behind.

Left to right

: Unity, Tom, Deborah, Diana, Jessica, Nancy (plus French bulldog), Pamela.

Read on for a preview of

A much-praised biography of the most brilliant of the Mitford sisters, who dazzled and scandalised interwar high society with their wit and sometimes controversial lifestyles.

1

The little grave at Swinbrook church is a sad sight now. One searches for many minutes, eyes wandering over the whiter tombstones, and the shock of finding it is considerable. Can this possibly be right? It is like a grave from two hundred years ago: the grave of a forgotten and anonymous person, of a poor serving girl who died alone and unlamented. It is covered with the thick damp lace of greenish moss, and there are no flowers.

On it are written, in plain script barely legible beneath the decay, the words:

NANCY

MITFORD

, Authoress, Wife of Peter Rodd, 1904–1973. Above the words is carved a strange fat animal, which is in fact a mole taken from the Mitford family crest. Nancy disliked the sign of the cross because she thought it a symbol of cruelty. So her sister Pamela, also buried in Swinbrook churchyard, chose for her the mole, a neat eccentric image that in later life was embossed on Nancy’s writing paper. An aunt of hers wrote to say how much she loved the letterhead: ‘your charming little golden cunt (Glostershire of my young days for moles, few people now know what it means).’ ‘

She’s

not in the Tynan set,’ Nancy had remarked. Beneath the earth, then, she may be laughing: her favourite thing in the world.

Yet as one of England’s most devout Francophiles she had dreamed of a burial at Père-Lachaise cemetery, ‘

parmi ce peuple

’ – as Napoleon put it – ‘

que j’ai si bien aimé

.’ She called it the ‘Lachaise dump’, but that was just her Englishness coming out. She loved the place. What she no doubt imagined was lying in florid, elegant state between Molière, La Fontaine, Balzac and Proust: a comforting thought, as if death were merely a continuation of her glittering Parisian middle age. As in Dostoevsky’s story ‘Bobok’, the buried people would simply carry on with the gossipy, deliciously trivial life that they had lived overground. ‘We’ve already passed enough friends to collect a large dinner party, a large amusing dinner party’, says Charles-Edouard de Valhubert in Nancy’s novel

The Blessing

, as he walks among the graves with his English wife. And then: ‘Is it not beautiful up on this cliff?’

Nancy dreamed of beauty around her in death. ‘I’ve left £4000 for a tomb with angels and things’, she wrote to Evelyn Waugh ten years before she died. ‘Surely it’s an ancient instinct to want a pretty tomb?’ She also dreamed, in a way that would have amused, but irritated Waugh like a verruca, of a heaven that was really like fairyland, full of the people she had loved, along with sexy men such as Louis XV and Lord Byron – ‘I look forward greatly. Oh how lovely it will be’ – and with

The Lost Chord

playing. ‘And an occasional nightingale.’