Tango

Authors: Mike Gonzalez

TANGO

The Reverb series looks at the connections between music, artists and performers, musical cultures and places. It explores how our cultural and historical understanding of times and places may help us to appreciate a wide variety of music, and vice versa.

Series editor: John Scanlan

Already published

The Beatles in Hamburg

Ian Inglis

Van Halen: Exuberant California, Zen Rock'n'Roll

John Scanlan

Brazilian Jive: From Samba to Bossa and Rap

David Treece

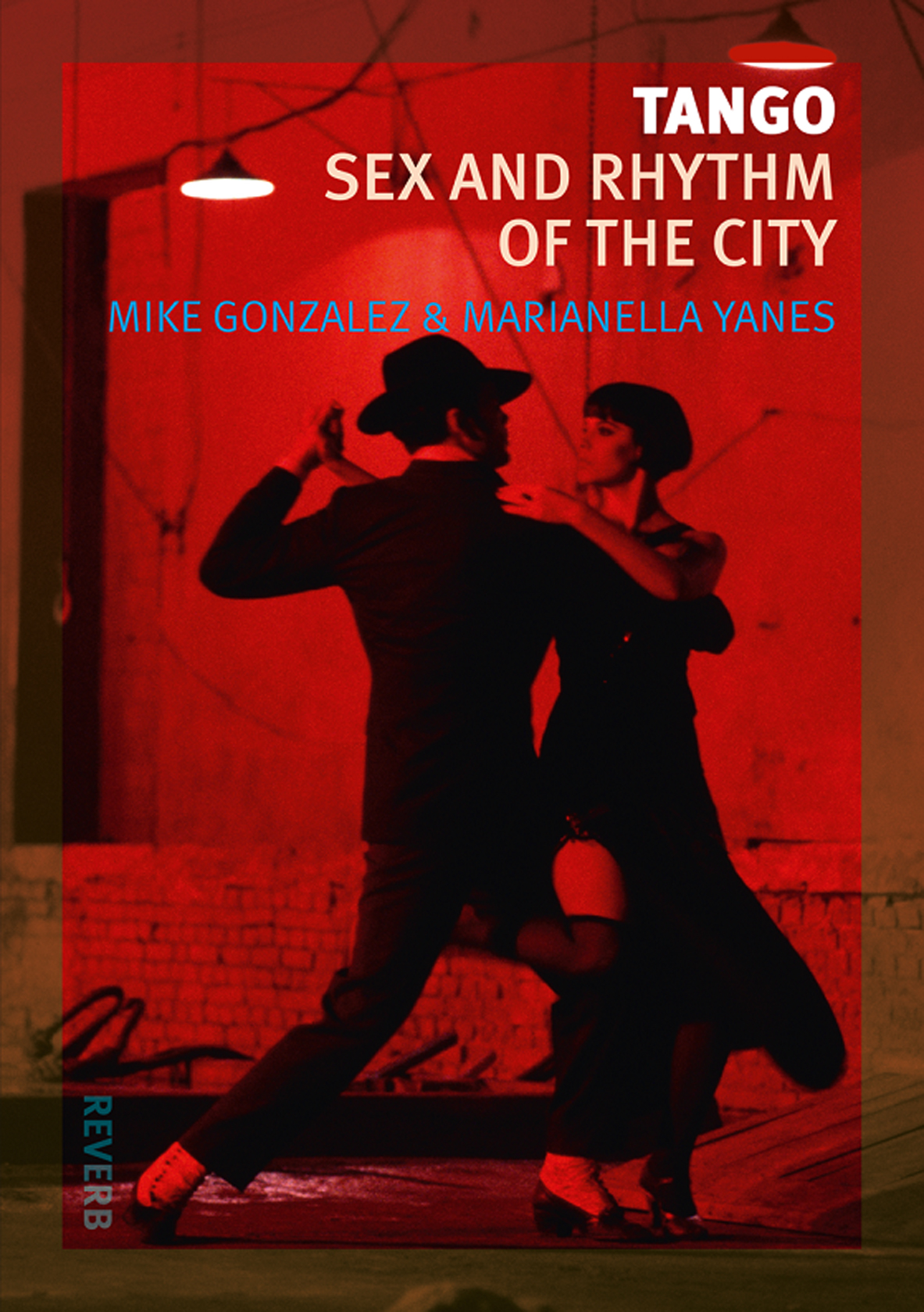

Tango: Sex and Rhythm of the City

Mike Gonzales and Marianella Yanes

TANGO

SEX AND RHYTHM OF THE CITY

MIKE GONZALEZ AND

MARIANELLA YANES

REAKTION BOOKS

With thanks to Antonio, my father, who loved Gardel; Elena and Candelario for the tangos that you sang; Benito Velasco, for his tango club in Caracas

.

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

33 Great Sutton Street

London

EC

1

V

0

DX

,

UK

First published 2013

Copyright © Mike Gonzalez and Marianella Yanes 2013

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain

by Bell & Bain, Glasgow

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

e

ISBN

: 9781780231457

CONTENTS

7 ASTOR PIAZZOLA AND TANGO NUEVO

PROLOGUES

TANGO MINE: MARIANELLA'S STORY

My home in Caracas was a place of peace at a turbulent political time, perhaps because it was a temple of women, to which men were invited at weekends. My sisters and I, the spoiled children of my nine aunts who shared our weekends and its endless meals, mimicked in our small way the steps and the lyrics that emerged from the vinyl records spinning on the record player. The music was a mix of popular ballads, rancheras, son and mambos â all very useful when the time came to polish the floor in preparation for an evening's dancing. In those days the floors were polished with hot wax dissolved in paraffin, a process so dangerous that the children had to be kept out of the room until the concrete floor tiles were covered. Then we were allowed in to help with the polishing by dancing on spongy rags tied to our feet â floor polishers were an unimaginable luxury. The job was done only when those coloured floors were glassy enough to reflect our faces in them. And we all sang while we danced. We could guess the mood of my mother, my grandmother, our neighbours and our wonderful aunts who accompanied us throughout our childhood, from the rhythm of the music. Disappointment in love, betrayal and rejection found some consolation only in the tango, the rancheras and the popular ballads. And that became even more intense and interesting when the television was turned on to watch the Dark Skinned Boy From Abasto, dear Carlos Gardel, in those melodramatic performances with which he graced Argentine cinema in the early Thirties. My aunts wept, my

mother sighed â she was never one for tears, like my grandmother, whose hard exterior softened only with that seductive suffering look that Gardel wore when he sang âHer eyes closed'. And my grandmother would say, âHow sad, the poor man, alone without his mother â and men without mothers always suffer!' It was a hint directed at my mother because she couldn't cook and had divorced and because her second marriage, from which my sisters were born, had not been blessed in church. My grandmother's criticisms were merciless, even though the situation was common to most working-class Latin American families. In general, couples got together without the approval of the Church or the civil registry; my grandmother herself was an example, with her three couplings, each of which had produced a child. Still, she did not expect her children to repeat her life story and the tango songs offered faithful portraits of her world.

But the big event of the weekend began after lunch, when the lovers appeared with their guitars to sing their passionate serenades, just like the lovers in Mexican films who sang beneath the balconies of their beloveds. The songs â tangos, boleros and rancheras â sounded authentic in their mouths, turning their dramatic lyrics into declarations of love that in that feminine space fertilized the unions and the separations of the future. There were the sisters in love with the same man, the men seducing several of the sisters, the bedroom secrets, the unexpected pregnancies, the jealousies, flirtations and rejections that only alcohol or new secret passions could assuage.

There, surrounded by the seductive dances and the melodious strumming of guitars, I learned the melodramatic visions that each tango contained. I absorbed them so well that their tragic vision of the world became words in the dialogues between the actors in the soap operas that I wrote for Venezuelan television.

Tango is more than a tuneful entertainment: it is a portrait of poor men and women, it is a sharp prick of hunger and thirst, it is a desolate road to homes overwhelmed by need. But at the same

time, it is the undefined pleasure of the forbidden. The solitude of a prostitute's empty room, the absence of love, the warmth of a Sunday family dinner, the things you left behind and the things you never achieved. The loss of a mother â that miraculous woman who would embrace you and expect only a brief kiss in return. The hardest thing was that the tango left us with a feeling of the loss of a country, of rootlessness, of the absence of that sense of belonging that tango reflected. And it expressed the need to construct and create a new life out of nothing. Hence

lunfardo

, the special language of tango. I reinvent language in order to belong, but I base this new language on what I have forgotten in order to become what I am. It is a language of immediate reference; it speaks of the immigrant's life in poverty.

These were the lyrics, the music and the violent and seductive steps of the tango. It is a temptation to dance tango, but not the kind of temptation that drags you to the dance floor to try it and see. Every movement, every gesture, every encounter demands preparation. Like lunfardo, the tango has to be learned over time. Its syncopated notes draw you in, absorb you, but learning its rhythm is the vital condition for the encounter. It is like an adolescent's initiation into adult life. First you listen to the music and let it seduce you. Before you dance, you learn how to dress for the milonga â the dance. For women: silk stockings, a garter belt, a skirt split on one side or in the middle. A low neckline. A flower in the hair and finally, high-heeled shoes. That is what seduces; it is a kind of fetish, with the long heel stroking the partner's leg. It is the smallest of gestures, a momentary touch, barely a caress to inspire those three minutes called âTango'. The man has his ritual too. The hat, the suit, the penetrating smell of lavender and perfume, the carnation or the violet in the lapel, the two-toned shoes with a small heel pointing forward. All these components gathered on the dance floor, in a ritual of pain, death, and the anguish of love and rejection, all in a ritual of despair that ends in that final embrace â the meeting and the farewell called âtango'.

THE DANCERS

It is an elegant shoe: high-heeled, and in gleaming patent leather crowned by a spat that holds the smooth black trouser leg. It lifts slightly, points forward and down, then slides along the floor, brushing against her fine black stocking. Her foot, resting back on spiked heels, arched and naked, lifts and responds in kind. Later, left foot follows right, now twisting, now engaging, now trapping her legs between his. The split skirt lets her respond, entwine and unravel, pirouette, a stroking capture of leg and thigh, hers open and suggestive, his dark and constrained by the tight-fitting suit.

The music is dramatic, fast, punctuated by sudden accents and shrill curls of violin and bandoneon. The narrative is a rhythm of lunge and counter, invitation and rejection. From the waist down, these restless bodies seek each other out in a ceaseless pursuit. Yet the upper body tells a different story. He leans over her at a constant angle, pushing and demanding, his back taut and unyielding; she bends slightly back, in an attitude of surrender. It does not seem to fit the sensuous encounter of legs and feet, so intimate, so full of desire.

Most perplexing are the eyes â the look, or rather its absence. There is neither challenge nor defiance, no dare and counter-dare. The engagement of the bodies is matched by a disengagement of the face. The dancers look at each other yet also beyond and into the distance; all that is here is indifference, a refusal to connect as resolute as the endless brushing of legs and thighs.

This is the paradox of tango.

1

STRANGERS IN THE CITY

Behind the grand domes and palaces of Genoa, I could see the mountains still. Apricale wasn't far away, just there, behind that second hill, where that tree is bending slightly in the wind. I grew up there, in dark cobbled streets with hundreds of corners and crannies where we could hide and play, along with the cats. There must have been a million cats in the village. You looked up and it seemed as if God had opened his hands and dropped the houses onto the hilltop and that they had tumbled down and stopped at crazy angles. We had our fields, my dad and I, up above the village, looking down. Some mornings you could hardly breathe when you got up there, particularly on winter mornings, when the wind was cold and the sun froze you in its light. But when my dad died, things changed.

The ship is moving now. I can hardly see. There are so many of us on deck watching, weeping, blinking so that the image of those mountains stays printed on the inside of our eyelids and we can take it with us to where we're going. Wherever that is. That man on the foredeck with the captain, the one in the frock coat and the top hat with a blue and white sash, he knows. He's the one who found us, who told us that on the other side of the world was a country waiting for us. There was land there. There were empty farms with houses that we could live in â the keys were above the door, ready for us. It was so vast, this place, that we would have to board a train and travel a day and a night. But

first they would give us a room in a hotel, and food. And they would welcome us.

I can hardly see my hills now. I can see Genoa, disappearing into the mist. Everyone is crying now, waving â but who to? Who knows how long it will be before we come back here, to Liguria. Perhaps we will come back with new families, and perhaps we will travel in the cabins, with the gentlemen. Perhaps?

IMMIGRANTS

In 1869, Buenos Aires had 223,000 inhabitants. A single generation later, in 1914, it was the largest city in the hemisphere after New York, with a population of just over 2 million. Most dramatically, nearly 48 per cent of the city's inhabitants were foreign born. Buenos Aires had been transformed in these few years âfrom a riverside town to a modern metropolis'.

1

The city had not only changed in size in those years; it had become profoundly cosmopolitan, diverse, home to a variety of languages and cultures. And at the same time, a yawning gulf had opened up between the old city centre and the wealthy suburbs, with their elegant, well-heeled residents, and the districts around the expanding port. Here was the melting pot in which the new city was being forged.