Task Force Black

Authors: Mark Urban

Also by Mark Urban

S

OVIET

L

AND

P

OWER

W

AR IN

A

FGHANISTAN

B

IG

B

OYS’

R

ULES:

T

HE

SAS

AND THE

S

ECRET

S

TRUGGLE

AGAINST THE

IRA

UK E

YES

A

LPHA:

I

NSIDE

B

RITISH

I

NTELLIGENCE

T

HE

M

AN

W

HO

B

ROKE

N

APOLEON’S

C

ODES:

T

HE

S

TORY OF

G

EORGE

S

COVELL

R

IFLES:

S

IX

Y

EARS WITH

W

ELLINGTON’S

L

EGENDARY

S

HARPSHOOTERS

G

ENERALS:

T

EN

B

RITISH

C

OMMANDERS

W

HO

S

HAPED THE

W

ORLD

F

USILIERS:

H

OW THE

B

RITISH

A

RMY

L

OST

A

MERICA BUT

L

EARNED TO

F

IGHT

LITTLE, BROWN

First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Little, Brown

Copyright © 2010 Mark Urban

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

eISBN: 978 0 748 12002 4

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library.

Little, Brown

An imprint of

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DY

An Hachette UK Company

www.hachette.co.uk

Contents

Copyright

Preface

Preamble

: The Secret War

1 Mission Paradoxical

2 Into the Blood

3 The Soldier-Monk

4 Building Networks

5 Target AQI

6 The Jamiat

7 Beyond Black

8 The Kember Outcome

9 Operation LARCHWOOD 4

10 Endgame For Zarqawi

11 The Battle for Baghdad

12 The Awakening

13 Choosing Victory

14 The Coming Storm with Iran

15 America’s Surge

16 The Khazali Mission

17 Al-Qaeda’s Surge

18 The Tide Turns

19 The V Word

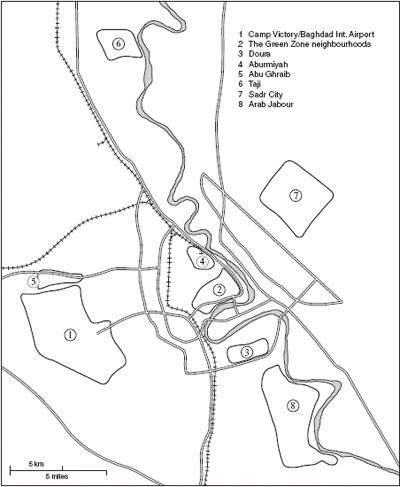

Baghdad

Basra

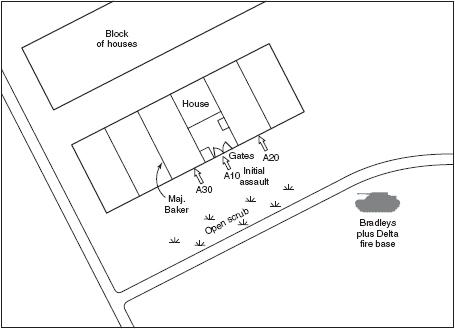

Operation ABALONE, Ramadi, 31 October 2003

Operation LARCHWOOD 4, Yusufiyah, 16 April 2006

Arab Jabour Operation, 21 November 2007

Late in 2005, I was waiting for an RAF plane home from Iraq when a large group of passengers arrived in the tent at Basra airport. There were about sixty men, divided evenly between an older heavier-set mob and younger, more sprightly-looking types. They were respectively members of the SAS and the Special Forces Support Group.

In their appearance these special forces seemed to be completely ‘out and proud’. For one thing, they were all wearing civilian clothes, whereas all other passengers for the Tristar home were following the rules about uniform. For another, many had chunky labels on their daysacks with things like ‘Jim, A Squadron, Hereford’ written on them.

During our wait for the flight I was joined in the struggle to get hot water out of a faulty boiling vessel by one of the squadron members, who had a few weeks earlier been held prisoner in the Jamiat police station several miles away in the centre of Basra. I had seen his undisguised face on TV pictures as they were pulled down into the BBC, and we briefly shared our frustration at the brew famine.

Since my encounter with A Squadron, members of UK special forces have adopted a different camouflage pattern from the rest of the British Army – but the same as is often used by top-tier US special ops soldiers. In short, then, the SAS or SBS, by using these outfits or civilian clothes in certain military situations, for example in camp or when travelling on forces’ flights, revel in their reputation as their country’s military elite and, you might say, why shouldn’t they?

The odd thing about this brazen attitude is that it sits uneasily with the culture of secrecy which many of those involved in the world of intelligence and special operations would like to impose. Members of Britain’s special forces are expected to abide by a lifelong duty of confidentiality in much the same way as those who work for MI6 or GCHQ. But there are two obstacles to this being achieved: in the first place, many of those on the inside allow the ego that comes with their ‘special’ status or superb physical fitness to evolve into a desire for publicity. One only has to look at the many SAS books or newspaper articles relying on well placed leaks to see this.

A second reason for the high public profile of the SAS in particular is the lethality of their business. This is not a matter of discreet agent recruitment or coming up with a clever computer algorithm, as the intelligence professionals’ world is. Special forces soldiering, particularly in the conflicts since the 9/11 attacks, is a high-intensity, deadly business involving face-to-face confrontation with some of the world’s most ruthless terrorists. It is unsurprising, then, that the public interest in what these soldiers do is very high. Combine public interest with the desire of many in the military to talk, and you have fertile ground for a book like the one that follows.

My desire to write it came about on another Iraq trip – one to Baghdad in September 2008. As coincidence had it, I ran into a succession of former intelligence and military types who had read

Big Boys’ Rules

, my earlier book on covert operations in Northern Ireland, were keen to shake the author’s hand and egged me on to write something similar about Iraq. Mark McCauley, the cameraman working with me on that trip (and during quite a few scrapes in Iraq and Afghanistan), added his weight to the argument, noting that my various trips to Iraq had given me the level of knowledge and access necessary to carry out such a sensitive project. So I began my own reconnaissance – to see whether it would be possible to write such a book.

It was clear to me that the scope for this would have to be far wider than just the SAS, as indeed my earlier work

Big Boys’ Rules

had been. The special forces sometimes see themselves as the scalpel wielded by other hands, the senior commanders and intelligence types needed to gain the information vital for success. Indeed, without this direction ‘the Regiment’ can seem, as one Northern Ireland policeman once rudely put it, like ‘plumbers who think they are brain surgeons’. As will become clear in this narrative, this was also true in Iraq, where the flow of accurate intelligence and evolution of a strategy to target certain elements of the insurgency were the essential preconditions for success. So while many may see this as an ‘SAS book’, I would argue it is something far wider and indeed more significant than that.