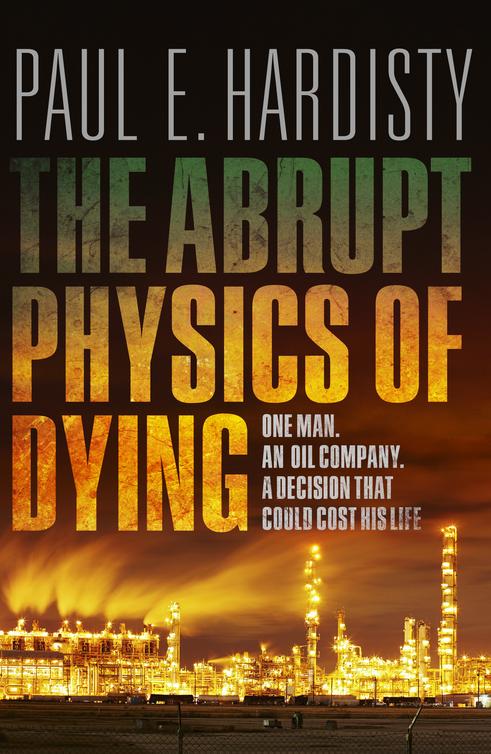

The Abrupt Physics of Dying

Read The Abrupt Physics of Dying Online

Authors: Paul E. Hardisty

PAUL E. HARDISTY

When the sky is torn

When the stars are shattered

When the seas are poured forth

When the tombs are bust open

Then a soul will know what it has given

And what it has held back

The Holy Qu’ran

, Sura 82: 1–5

- Title Page

- Epigraph

-

- Part I

- No Way Back from Here

- The Sun

- You Should Pray

- Who You Might Have Been

- Not Yet a Commodity

- A Melody of Spokes

- Getting the Tone Just Right

- Bulgarian Gangbang

- Twisting by the Pool

- That Stuff Will Kill You

- Locked in

- A Way of Saying Thank You

- One Man Is Nothing

- The Rest of Your Life

- Moving the Ball

- In Paradise

- No Shortage of Bastards

-

- Part II

- First Kill

- Bang, You’re Dead

- Why You Do Nothing

- Cathinone Sprint

- Liberal Shit

- Swimming in the Disorder

- Childhood Drawings

- The Chemicals of Violence

-

- Part III

- This Will Hurt a Bit

- Prophets of Chaos

- The Illusion of Commitment

- Missing Octaves

- Such a Small Thing

- Truth

- You Will Burn

- Killer Hypothesis

- Flirting with Extinction

- Immiscible All

- Our Tortured Country

- Unburied Lies

-

- Part IV

- Unanswered Questions

- The Weight of Sin

- Allah Knows

- A Mass Grave of Stars

- Just Economics

- Flailing in the Void

- The Killing Price

- Strange Calligraphy

- All the Empty Places

- The Way It Was Supposed To Be

- The Kindness of Strangers

- Maybe That Was Good Enough

-

- Part V

- A Problematic Resurrection

- The Accused

- Very Soon Dead

- Angels and Men

- The Conflict Within

- All That Hateful Beauty

- Everything That Had Led Him Here

- Entropy

- Saint Fucking Mandela

- A Place You Can Go

- The Things He Would Never Do

- The Right Thing

-

- Acknowledgements

- Copyright

The Kalashnikov’s barrel was surprisingly hot. He imagined the brand the flash suppressor would leave in the middle of his forehead, the desert sun heating the metal to burn skin, a neat round scar marking him forever as godless, or, if it were a hole, dead. It had been a long time since someone had pointed a gun at him.

Claymore Straker sat motionless in the passenger seat of the Land Cruiser, staring down the barrel at the dark, bloodshot eyes of the man whose finger was a mere twitch away from redistributing his brains, and waited for the panic to rise in his chest. Facing the end of his time, calculating a life’s worth, weighing his heart against a feather – surely these things should be cause for terror, or at least reflection. But he felt neither fear, nor panic, nor the urge to run. What came was more a sense of a long journey gone wrong, the feeling of arriving at what should have been the destination, only to find the sunburned skeleton of a home, the wood long since scorched the colour of bone, the parched hills beyond showing through open windows and fallen walls, the cloudless sky piercing the gaping holes in the roof. Thirteen years ago he’d taken a wrong turn. And somehow he’d ended up here, looking back along the length of a gun barrel at a kid not much older than he’d been, back then, when he’d killed for the first time.

A bead of sweat tracked down his temple and dripped from the hinge of his jaw to spatter on his shirt. The sound it made was that of an insect hitting a windscreen. Another followed, the same rupture. It had been only a few minutes since they had been forced to the roadside, and already the inside of the vehicle was like an incinerator. What had led this kid here? Clay wondered. Had he had a choice? Was he, as Clay had been back then, desperate to prove himself, terrified of screwing up, preferring death over the humiliation of failure? And now that he was here, in the temple, what would he learn about himself?

The kid was speaking to him now, yammering in high-pitched Arabic. He wore a charity drive jacket over a faded

thaub

that probably hadn’t been washed since it was made. The cloth wrapped around his head – the traditional Yemeni headscarf, the

keffiyeh

– looked like a roadside mechanic’s shop rag, torn and stained. Clay figured the kid for eighteen, no more, despite the weather in his face – much younger than the other gunman who now stood at the driver’s side with weapon levelled at Abdulkader’s neck.

The kid pushed the barrel harder into Clay’s forehead, forcing his neck back into the headrest. Again, the same words, louder this time, more insistent. He seemed to be looking at the steering column, the keys.

‘Look, I don’t understand you,’ Clay said. His voice was calm and even, someone else’s. ‘

La’a

atakalim arabee

.’ I don’t speak Arabic.

‘He wants you to get down from the car,’ said Abdulkader. ‘Slow. Keep your hands where he can see.’

Clay heard the grating sound of the driver’s side door swinging open. The other gunman barked out something in Arabic and the kid snapped his rifle back from Clay’s head and stepped away from the open window, the weapon now set to drive rounds through the thin metal of the door, straight into his torso. Clay stepped out onto the pulverised dust of the road. By now Abdulkader was beside him at the roadside. They stood with their backs to the vehicle, hands clasped behind their heads. The two tribesmen stood facing them, the car keys dangling in the older man’s hand. They seemed to be

examining Abdulkader: he was clearly one of them, a Hadrami, perhaps not from this part of the Masila, but not an outsider. He spoke the same guttural dialect, carried his grandfather’s curved, rhino-horn-handled dagger, the

jambiya

; he, too, could trace his lineage back to the Prophet.

The older man was speaking now, spitting out rusty-iron words, jerking the hoe of his beard towards the ground as if he were trying to cut a furrow in the sand. Abdulkader answered. A conversation ensued, the man questioning, Abdulkader’s gravel-road voice rumbling in response. This continued for some time, the tone modulating between near fury and friendly chat. And then the older man laughed. The few teeth he had were stained a deep shade of brown, like weathered tar. He reached over and put his hand to the barrel of his kinsman’s rifle and lowered the muzzle until it pointed to the ground at Clay’s feet.

‘We will go with them,’ said Abdulkader. ‘Sit in the back seat.’

Clay did not move. As long as they were still out here, on the road, talking, they had a chance. The moment they got back into the car, they would be prisoners.

‘Tell them to go home, Abdulkader. This doesn’t have to end badly for anyone.’

Abdulkader looked at him a moment, turned to the older man, translated. The older man listened, paused a moment as if reflecting on what he had heard, then fixed his gaze on Clay.

‘

La

,’ he said, jerking the barrel of his rifle towards the car. No. ‘

Emshee

.’ Move.

‘Please, Mister Clay, do as he says,’ said Abdulkader, turning and climbing into the front passenger seat.

Clay planted his feet, stood facing the two gunmen, the older man frail, wizened, his beard tinted with henna, the kid taller, with deeply veined arms and a long sinewed neck that sprouted from narrow, slumped shoulders. He stood with the muzzle of his AK pointed down. Like him, it looked battered, poorly cared for. Fear swirled in his eyes.

Clay opened his palms, showed them to the gunmen, the universal sign of greeting, of supplication: I hold nothing that can hurt you.

‘

La’awh

samaht

,’ he said. Please. ‘Let us on our way, before someone gets hurt.’ He looked back along the road towards the Kamar-1 well. ‘

Jeyesh’a

,’ he said. Army. ‘The Army is close by. Tell them, Abdulkader. If they go now they’ll be safe.’ They had no escort, but it was worth a try.

The kid blinked twice, a question forming on his face. The elder tribesman, clearly the leader, barked out something in Arabic. The boy levelled his weapon and jabbed it into Clay’s ribs. The safety was off.

Abdulkader started translating, pointing back along the road, but the old tribesman cut him off, silenced him with a single word.

Clay could feel the AK’s muzzle trembling, see the kid’s hand shaking on the pistol grip. He looked into the young man’s dark brown, almost featureless irises, the black retina, and locked them.

‘No way back from here,

broer

,’ he said in English, knowing the kid would not understand.

‘Please, Mister Clay,’ called Abdulkader from the car. ‘Get in. He will shoot you if you do not.’

The kid flicked a glance towards his kinsman, gave his AK a jerk, digging the muzzle hard into Clay’s chest.

Clay stepped back, put a half-step between them, hands still clasped behind his neck. He was a head taller than the kid, had a good twenty kilos on him, more. Clay reached slowly into the breast pocket of his shirt. ‘I have money,’ he said, pulling out a thick fold of Yemeni

rials

and holding it out towards the gunmen. ‘

Faddar

,’ he said. ‘Please, take it and go.’

The kid’s eyes widened. The older man frowned, extended his stance, made to swipe Clay’s fist away with the barrel of his weapon.

It was the mistake Clay had been waiting for. He opened his hand, caught the barrel in his palm, and tightened his fingers around the wooden forestock. The AK’s muzzle pointed skyward. Yemeni

banknotes fluttered to the ground. Time slowed. Clay started to rotate the ball of his right foot, the pivot that would swing him away from the kid’s line of fire and bring his weight around into the old man taking shape – his knees starting to bend, centre of gravity lowering, left elbow drawing back for the strike. The calculations were already done in his head: twenty-five hundred Newtons of force delivered with an angular momentum of twenty-six joule-seconds. Enough to crack bone, shatter cartilage. In a heart-skip it would be done. The old man would be down, the AK would be pointing at the kid. Clay could feel rage fire its waking reactions – that fission improperly buried in his core, suspect and unstable. Soon it would start to cascade and then it would be too late. There could be only two outcomes, and in each the kid would die.

Clay opened his palm and let the rifle go. He raised his hands slowly back to his head. He’d held the barrel for a quarter of a second only, long enough that the old man would know what could have happened. The last banknotes settled to the ground like winter leaves.

The old man jerked his weapon away, stepped back. He glanced quickly at the kid as if embarrassed at being caught out, then glared at Clay. The kid still hadn’t reacted, just stood there slack-mouthed, the killing end of his weapon still inches from Clay’s chest, the fear in him palpable now, a stench that thickened the air around them.

Abdulkader said nothing, just sat in the Land Cruiser’s passenger seat as if resigned to this fate, this direction that events were taking. Soon, its trajectory would harden and grow strong and send them all tumbling into a place he had spent the last decade trying to forget.

The older tribesman raised his weapon, aimed it at Abdulkader’s chest. The safety was off. He spoke. The anger rose in his voice. The message was clear.

Clay took a deep breath, looked into his driver’s eyes. Abdulkader had joined the company as a driver two years ago, just after first oil. The money he earned helped him to support his two wives and seven children. Although Clay hadn’t known him long, a year perhaps,

he’d grown fond of this man, his hundred-kilometre silences, his deep, considered logic, the gentle way he had with his children – balancing the littlest ones on his knee, laughing as he watched his sons kicking an old under-inflated football around the dusty paddock, the way he cared for his goats, pulling a stone from a kid’s cloven hoof, feeding a sick doe with his calloused palm.

Clay raised his hands. ‘

Tammam

,’ he said, turning slowly and opening the car door. OK. ‘

Ma’afi

mushkilla

.’ No problem. Easy. He stepped slowly to the car, climbed into the back seat.

The older tribesman lowered his weapon, walked around to the driver’s side, got in behind the wheel, started the engine. The kid signalled Clay to move across the seat, got in, closed the door. After ten minutes on the trunk road, the older tribesman slowed the vehicle and turned it onto a narrow stone track that skirted the edge of a broad scarp. Clay could just make out the headworks of the new Kamar-3 well in the distance. Looking down from the scarp, the land fell away into a broad graben dissected by the root ends of dozens of smaller wadis. Eventually some of these coalesced to form one of the main tributaries of Wadi Idim, a deep canyon that ran down to the escarpment and burst out onto the coastal plain.

The vehicle lurched along the rocky track for what could have been half an hour, maybe more, the terrain a monotony of serried gullies and swales cut into the twisting contour of the scarp’s edge. From the air, this landscape had the appearance of a slab of dried flesh, hooked and hung, the deep wadi dendrites like dark arteries in negative relief. But here, tethered to the ground, straight-line distances were meaningless, one mile of map progress won only with two miles of relentless contouring around mesa and wadi, a journey of seemingly endless wanderings.

At the apex of one of the gullies, indistinguishable from any of the others, the old tribesman stopped the car. He opened his door, stepped to the ground and crouched to lock the hubs. Then he got back behind the steering wheel, put the Land Cruiser into

four-wheel

drive, and started the vehicle lurching down the slope.

From the back seat, Clay could make out only the faintest indication of some sort of track, a few stones piled here and there, a shelf of wheel-crushed slate, occasional tyre marks in softer sand. Through the heat haze, away in the distance, the dark clefts of a series of

steep-sided

wadis cut deep into the limestone bedrock. The cliffs of each facing wall shone white in the distance like the teeth of some Triassic carnivore reborn from the rock of its deathbed. The satellite imagery had shown no settlements anywhere near here. From memory, that whole series of wadis, still perhaps ten or more kilometres away, petered out somewhere west of Idim, and had appeared to be inaccessible by vehicle. Not a bad place to be if you were trying to hide, or if you didn’t want witnesses.

Clay reached across the seat back and touched Abdulkader’s shoulder. ‘What do they want?’ It wasn’t money, and it wasn’t Abdulkader’s battered old Land Cruiser. Were they to be hostages, pawns in the increasingly bitter feud between the tribes, the government, and the oil companies, or just examples, their bullet-holed bodies a warning to those who might think the tribes irresolute and fractious?

The old man turned and glowered at him. Abdulkader said nothing.

Clay assessed options. He had pushed as hard as he dared back at the roadside. By the way the old guy was driving, it was clear he was determined to get away from the road and out of sight as quickly as possible. The kid was nervous, twitchy, obviously inexperienced. His finger was on the AK’s trigger, not on the guard, and the safety was off. The muzzle was pointed at Clay’s ribs. Side on, Clay had little chance of disarming him before he got off a shot. And with Abdulkader in the passenger seat directly in front, the risk of trying was too great. He would have to wait.