The Admiral and the Ambassador (3 page)

Read The Admiral and the Ambassador Online

Authors: Scott Martelle

The Reverend Paul-Henri Marron, a Swiss Calvinist who apparently had never met Jones, delivered a eulogy for the legend, not the man. Marron glossed over the sexual scandal and court intrigues that had driven Jones from Saint Petersburg and romanticized the dead man's motives, bathing him in a revolutionary lightâfitting, for the time and the place. “Paul Jones could not long breathe the pestilential air of despotism,” the minister said. “He preferred the sweets of a private life in France, now free, to the

éclat

of titles and of honors which ⦠were lavished upon him by Catherine. The fame of the brave outlives him; his portion is immortality.” Then the minister urged his fellow

citoyens

to let Paul be their inspiration. “What more flattering homage could we pay to ⦠Paul Jones, than to swear on his tomb to live or to die free? It is the vow, it is the watchword for every Frenchman.”

The grenadiers fired a salute into the air, and the small gathering broke up. The mourners began making their way south in the gathering dusk, back along the road to the walled city, to the lights, and to the revolution. The gravediggers turned to their final task, shoveling the rich French earth onto the coffin of the man who would become known as the Father of the American Navy, and whose grave would soon be lost in the tumult of war.

Washington, DC, March 4, 1897

Horace Porter sat atop a parade stallion as he waited for a carriage to emerge from a nearby gate. It was a few minutes after 10 A

M,

and the blustery winds that ushered in the dawn had died down, leaving a pleasantly sunny but chilly day in Washington. Bad weather, of course, is bad news for a parade, so the clear skies gave Porter one less thing to worry about. It was his parade that was at stake on this late-winter morning, and he wanted everything to go according to plan. The celebration was the first of a series of high-profile events in which Porter would play a central role over the next few weeks, and while he wasn't a man prone to anxiety, one suspects he was well aware of what failure would mean for his reputation for probity, discipline, and reliabilityâeven if no one truly expected him to control the weather.

1

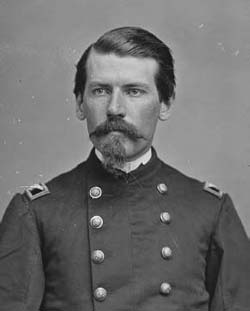

Porter's sixtieth birthday was a month away, and the years had left their marks. He was in fine health, but his hair and mustache had grayed, and

his face sagged around the cheeks. Still, he maintained the military bearing learned a half century earlier as he rose to the rank of brigadier general in the Union Army and as a top aide to General Ulysses S. Grant. After the war, Porter followed Grant into politics. Although Porter had long ago moved into civilian life, on this morning he sported a full dress uniform: dark blue jacket and pants with a gold belt and oversized epaulets, a broad sash, medals on his chest, and a plumed black hat on his head. A new sword dangled in its scabbard at his side, a gift from his staff to commemorate this day for which they had planned and worked most of the previous four months.

2

Porter's horse stood at the head of a small detachment of cavalrymen in the middle of Pennsylvania Avenue. Rows of forty-five-star flags flapped over the heads of thousands of people overflowing the sidewalks and spilling noisily into Lafayette Square. Porter ignored the human din and kept his eye on a nearby gate, waiting for a carriage to emerge bearing his friend Major William McKinley and President Grover Cleveland. The carriage would be Porter's cue to spur his horse and start his small squadron, the official escort on the short trip from the White House to the Capitol, where McKinley, an Ohio native and former Republican congressman and governor, would soon be sworn in as the twenty-fifth president of the United States.

The election had been groundbreaking for American politics, shifting tactics from old-style parades and rallies to a more media-savvy, and media-using, strategy. The main issue as the nation shouldered its way out of an economic depression had been money. McKinley ran on a “sound money” platform, pinning the value of the US dollar to a gold standard. Democrat William Jennings Bryan stood for “free silver,” a policy that would have pegged the value of the dollar to silver, making goods more affordable and boosting the wealth of western silver miners. Gold won, but the real engine behind McKinley's victory was the maneuvering of his campaign manager, Ohio millionaire and powerbroker Mark Hanna, who built the campaign around letters, pamphlets, and books provided free to the voters. The material explained McKinley's monetary and trade policesâdry stuff in the best of timesâbut also reinforced McKinley's image as a sober and prudent leader, an attractive force of stability in times of financial upheaval

and uncertainty. At the time, political radicals were turning to the gun and the bomb to try to overthrow capitalism, and labor activists were sparking strikes to wrest better wages and working conditions from men who were just as strident in their refusals to grant them.

Mounting such an “educational campaign” of literature, as McKinley's political advisors called it, took a lot of cash, and Porter, as it happened, was exceedingly good at raising money. Porter brought in hundreds of thousands of dollars in donations, underwriting a campaign that overwhelmed the Democrats and helped propel the Republican Party to national dominance, until the Great Depression caused another political realignment and sent Franklin Delano Roosevelt to the White House.

3

While the 1896 election was significant for the nation, it was also a critical moment for Porter. He had been on the national political stage beforeâby now, in fact, he was an old and seasoned handâbut McKinley's victory would mark the start of a fourth chapter in his life and send him on an adventure to rival that of his war years.

Porter was born in Huntingdon, Pennsylvania, in 1837, the son of David R. Porter, a businessman turned politician who, two years later, would be elected governor of Pennsylvania. The elder Porter himself was the son of a Revolutionary War veteran, Andrew Porter, who began as a captain in the marines aboard the

Effingham

but then quickly transferred to the artillery. Eventually achieving the rank of colonel, Andrew Porter fought at the battles of Princeton, Brandywine, Germantown, and Trenton.

Before the war, Colonel Porter, who had a penchant for mathematics, ran his own small private school in Philadelphia, but after the war he settled into farming in Norristown, Pennsylvania, and eventually became a surveyor, helping establish the Pennsylvania state boundaries. His son David Porter, despite his success in politics, lost fortunes at least twice during economic depressionsâfirst running ironworks, then as a railroad investorâbut those troubles occurred before and after Horace, his sixth son and seventh child to survive into adulthood, was raised.

4

Horace Porter grew up primarily in Harrisburg, attending school during the day and working at his father's ironworks in the after hours. A tinkerer, he created several small refinements to the machinery in the ironworks and developed an interest in engineering. As a governor's son, he also absorbed lessons in politics and military affairs. General Sam Houston was a friend of Porter's father and an occasional visitor, and the young Horace would listen to the famous Texan's stories of battles from the War of 1812 to the fight for Texas independence to the Mexican-American War. He also eavesdropped on the adults' debates over West Point (Houston disliked it) and slavery (Houston was for it).

The elder Porter also counted James Buchanan, then the US representative to the Court of St. James's in London, among his friends, and Horace, through their letters, “had his first glimpse of that European world to the problems of which he was later to give so much thought.”

5

When he was thirteen years old, Porter was sent off to a boarding school in Lawrenceville, New Jersey, where he excelled academicallyâfirst in his class in Latin, French, and mathâand also organized a small military company of students.

As he neared graduation, Porter sought an appointment to West Point but missed the cut. Porter enrolled in the Lawrence Scientific School at Harvard instead and tried again the next year for West Point, this time more forcefully. During his midwinter break, Porter traveled to Washington to lobby Ner Middleswarth, the congressman from his home district in Pennsylvania, for an appointment. It worked: Porter was admitted to West Point in 1855.

As a cadet, Porter studied engineering and trained in artillery and ordnance management. He was a generally good student in a class that faced severe erosion. Porter's entering class had eighty-one students; by graduation day five years later (one of only two West Point classes to follow a five-year program), fifty-five students were left.

6

Porter placed near the top across most of his subject areas, though he seemed to have trouble with French, placing thirteenth, then fifteenth, and then dropping to twenty-ninth. The cadet apparently hit the books, though, and by the 1857 term Porter was first in his French class too.

While Porter enjoyed the military training, he suffered the occasional mishap. During a horseback training drill, his mount reached out and bit the animal in front, which retaliated by kicking out a hind leg that “struck my right leg several inches above the ankle,” opening up a deep gash that wouldn't heal, Porter wrote his sister on September 20, 1858, from a hospital bed. Porter spent more than a week in the hospital before he had recovered enough to rejoin training and his classes.

7

West Point was an all-male bastion, but family members and girlfriends made regular visits and were quartered at the three-story West Point Hotel, fronted by a broad and deep wooden porch, which became the cadets' place to meet and woo young women. In the summer of 1859, Sophie McHarg, the daughter in a prominent Albany family, was staying at the hotel with a friend, Mary Satterlee, though the reason for their visit is unclear. Porter happened by while the two young women were on the porch, and was smitten with McHarg. They soon began courting, and after Porter graduated third in his class in July 1860, the couple became engaged. Porter spent the summer as an artillery instructor at West Point and that fall was assigned to the army's Watervliet Arsenal at Troy, just a few miles from Albany, a convenient posting for his romantic life. But his orders were soon to change.

8

In April 1861 secessionist troops in South Carolina opened fire on the US government's military installation at Fort Sumter, launching the Civil War. Porter was overwhelmed at Watervliet as orders escalated for supplies and weapons to be shipped to different Union outposts. He was sent on one clandestine mission to Washington, DC, to deliver reports deemed too sensitive for the mail. Wearing civilian clothes, he took the steamer

Daylight,

along with a contingent of Union troops and military supplies, to Hampton Roads and then up the Potomac, where the ship made it past Confederate gun emplacements without incident. At Washington, the ship was boarded by William H. Seward, the secretary of state, and President Lincoln, who told those aboard he felt compelled to personally thank each of them for their efforts. Porter delivered his messages and made his way back to Watervliet.

By October, Porter had received orders to join an expedition sailing to Hilton Head, and almost immediately he was engaged in action as the

Union troops shelled a Confederate-held fort (with Porter running his own small battery of artillery), then seized the ground after the rebels retreated.