The Aeneid (52 page)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

These, at least, are some of the things that have occurred to the translator, and in trying to express them I have had many kinds of help. The strongest has come from Bernard Knox, my teacher once and my collaborator now, whom I prefer to call a comrade. Much as we worked together on Sophocles’ Theban plays and the two Homeric poems, so we have worked on the

Aeneid

. Not only has he written the Introduction to the translation, but he has commented on my drafts for many years. And when I leaf through the pages now, his reactions ring my manuscript so completely that I might be looking at a worse-for-wear, dog-eared copy encircled by a scholiast’s remarks. Yet Knox’s gifts are more magnanimous than that. All told, he has offered me what I have needed most: “Doric discipline,” in Yeats’s words, and “Platonic tolerance” too. It has been my great good luck to work with such a man.

Aeneid

. Not only has he written the Introduction to the translation, but he has commented on my drafts for many years. And when I leaf through the pages now, his reactions ring my manuscript so completely that I might be looking at a worse-for-wear, dog-eared copy encircled by a scholiast’s remarks. Yet Knox’s gifts are more magnanimous than that. All told, he has offered me what I have needed most: “Doric discipline,” in Yeats’s words, and “Platonic tolerance” too. It has been my great good luck to work with such a man.

Michael Putnam has stood by the undertaking from the start, offering me his help in conversation, in encouragement, and even more essentially in his masterful writings about Virgil, which extend from matters of diction to the resonance of a simile or a symbol, to the dramatic construction of a scene, to the vision of the

Aeneid

. Still more immediately, with Putnam serving as classical authority, he and I have worked together closely to produce the Suggestions for Further Reading, the Notes on the Translation, and the Pronouncing Glossary that conclude the book. He has been swift in his pace, unstinting in his erudition, and the soul of generosity—I owe him “more than word can wield the matter.”

Aeneid

. Still more immediately, with Putnam serving as classical authority, he and I have worked together closely to produce the Suggestions for Further Reading, the Notes on the Translation, and the Pronouncing Glossary that conclude the book. He has been swift in his pace, unstinting in his erudition, and the soul of generosity—I owe him “more than word can wield the matter.”

Several other scholars and critics, cited among the Suggestions for Further Reading, have instructed me as well. Of the commentaries I would underscore those of R. G. Austin on Books 1, 2, 4 and 6; of R. D. Williams on Books 1 through 12; C. J. Fordyce on 7 and 8; K. W. Gransden on 8 and 11; Philip Hardie on 9; W. S. Macguinness on 12; and, often relayed by Knox as the occasion required, the commentaries of Conington et al., Mackail, and Servius. All their writings have been resources to me, assisting in matters that include the proper English phrase and syntax for the Latin, the background of Virgil’s place-names, their geographical locations, folk tales and founding myths, and the broad historical reaches of the Roman world.

Several modern translators of the

Aeneid

have helped as well. Each has introduced me to a new aspect of the poem, another potential for the present. “For if it is true,” as Maynard Mack proposes, “that what we translate from a given work is what, wearing the spectacles of our time, we see in it, it is also true that we see in it what we have the power to translate” (

The Norton Anthology of World Literature,

5th ed., p. 2045). So the help I have derived from others is considerable, and dividing them for convenience into groups, I say my thanks to each in turn. First, to those who have translated the

Aeneid

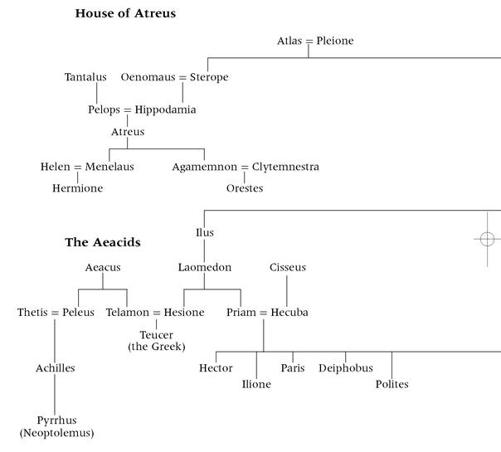

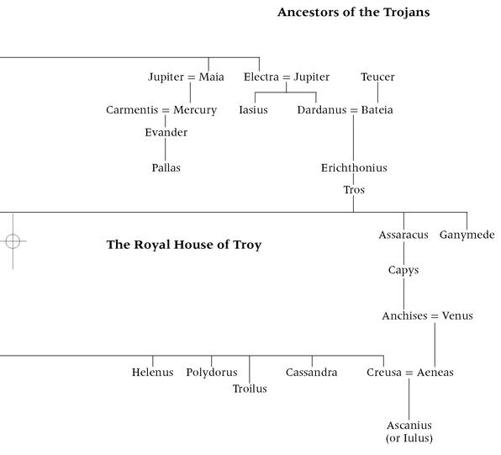

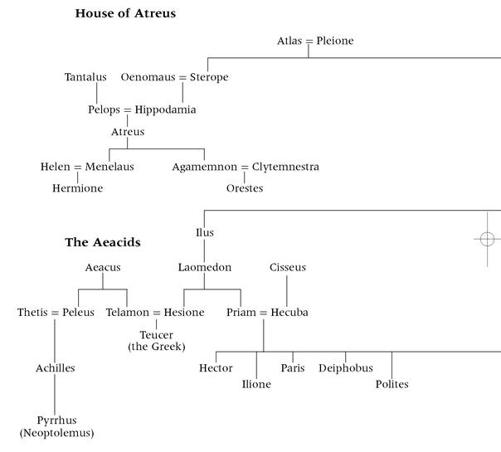

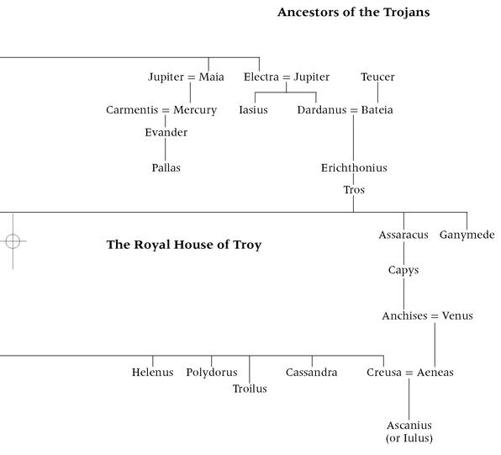

into prose: John Conington, edited by J. A. Symonds; H. R. Fairclough as revised by G. P. Goold; W. F. Jackson Knight (for his translation, and for the genealogical table of the royal houses of Troy and Greece drawn by Bernard Vasquez appearing within it); and David West (for his translation and also his comprehensive introduction to the poem). Each presents an example of accuracy as well as grace, and the stronger that example, the more instructive each has been in bringing me a little closer to the Latin. Next, my thanks to the translators who have turned the

Aeneid

into verse: F. O. Copley, Patrick Dickinson, Robert Fitzgerald, Rolfe Humphries, C. Day Lewis, Stanley Lombardo, Allen Mandelbaum (for his translation and also his extremely helpful glossary), Edward McCrorie, and C. H. Sisson. Each presents a kind of aspiration, a striving to find the strongest English line for Virgil’s Latin line; and I have learned from each in turn, probably most from Fitzgerald, for the Latinity of his stamina and his style.

Aeneid

have helped as well. Each has introduced me to a new aspect of the poem, another potential for the present. “For if it is true,” as Maynard Mack proposes, “that what we translate from a given work is what, wearing the spectacles of our time, we see in it, it is also true that we see in it what we have the power to translate” (

The Norton Anthology of World Literature,

5th ed., p. 2045). So the help I have derived from others is considerable, and dividing them for convenience into groups, I say my thanks to each in turn. First, to those who have translated the

Aeneid

into prose: John Conington, edited by J. A. Symonds; H. R. Fairclough as revised by G. P. Goold; W. F. Jackson Knight (for his translation, and for the genealogical table of the royal houses of Troy and Greece drawn by Bernard Vasquez appearing within it); and David West (for his translation and also his comprehensive introduction to the poem). Each presents an example of accuracy as well as grace, and the stronger that example, the more instructive each has been in bringing me a little closer to the Latin. Next, my thanks to the translators who have turned the

Aeneid

into verse: F. O. Copley, Patrick Dickinson, Robert Fitzgerald, Rolfe Humphries, C. Day Lewis, Stanley Lombardo, Allen Mandelbaum (for his translation and also his extremely helpful glossary), Edward McCrorie, and C. H. Sisson. Each presents a kind of aspiration, a striving to find the strongest English line for Virgil’s Latin line; and I have learned from each in turn, probably most from Fitzgerald, for the Latinity of his stamina and his style.

And finally, there are the unapproachables, all impossible to reach, who have caught the Virgilian spirit on the wing and turned it into words. I will mention only a few. John Dryden, who produced his

Aeneid

at the end of the seventeenth century, is far and away the first among them, and its greatness is anticipated, in brief, by his elegy “To the Memory of Mr. Oldham,” perhaps the most Virgilian poem that I know in English. Dryden’s work is preceded by certain Virgilian adaptations in the English Renaissance, particularly Marlowe’s

Dido, Queen of Carthage,

and followed by many selections, new as well as old, in Gransden’s generous edition of

Virgil in English

. Closest to me in time are Auden’s “Secondary Epic” and “Memorial for the City,” Allen Tate’s “Aeneas at Washington” and “The Mediterranean,” Robert Lowell’s “Falling Asleep over the

Aeneid,

” and several other works discussed in Theodore Ziolkowski’s

Virgil and the Moderns,

with its superb analysis of Hermann Broch’s

Death of Virgil

.

Aeneid

at the end of the seventeenth century, is far and away the first among them, and its greatness is anticipated, in brief, by his elegy “To the Memory of Mr. Oldham,” perhaps the most Virgilian poem that I know in English. Dryden’s work is preceded by certain Virgilian adaptations in the English Renaissance, particularly Marlowe’s

Dido, Queen of Carthage,

and followed by many selections, new as well as old, in Gransden’s generous edition of

Virgil in English

. Closest to me in time are Auden’s “Secondary Epic” and “Memorial for the City,” Allen Tate’s “Aeneas at Washington” and “The Mediterranean,” Robert Lowell’s “Falling Asleep over the

Aeneid,

” and several other works discussed in Theodore Ziolkowski’s

Virgil and the Moderns,

with its superb analysis of Hermann Broch’s

Death of Virgil

.

Of the more recent translators, I have known only a few in person, yet we all may know each other in a way, having trekked across the same territory, perhaps having had the same nightmare that haunted Pope throughout his Homeric efforts. “He was engaged in a long journey,” as Joseph Spence reports Pope’s dream, “puzzled which way to take, and full of fears” that it would never end. And if you reach the end, the fears may start in earnest. Your best hope, I suppose, a distant one at that (and for some not all that hopeful), is the one held out by Walter Benjamin in his famous essay “The Task of the Translator.” “Even the greatest translation,” he writes, “is destined to become part of the growth of its own language and eventually to be absorbed by its renewal” (p. 73).

Many classicists have helped as well, with prompting and advice, some viva voce and some in their writings: Paul Alpers, Charles Beye, Ward Briggs III, Edward Champlin, Andrew Feldherr, Andrew Ford, Eric Grey, Arthur Hanson, Georgia Nugent, David Quint, Sarah Spence, and James Zetzel. And many other friends, most of them writers, have helped with caution or encouragement or a healthy blend of both. Most heartening of all, none has asked me, “Why another

Aeneid

?” Each understands, it seems, that if Virgil was a performer, even in his writerly way, his translator might aim to be one as well. And no two performances of the same work—surely not of a musical composition, so probably not of a work of language either—will ever be the same. The tempo and timbre of each will be distinct, let alone its deeper resonance, build, and thrust. So there may always be room for one translation more, especially as idioms and eras change, and I thank the following friends for suggesting that I try my hand at Virgil: André Aciman, Christopher Davis, James Dickey, Charles Gillispie, Shirley Hazzard, Christopher Hedges, Robert Hollander, John McPhee, Jeffrey Perl, Theodore Weiss, and Theodore Ziolkowski.

Aeneid

?” Each understands, it seems, that if Virgil was a performer, even in his writerly way, his translator might aim to be one as well. And no two performances of the same work—surely not of a musical composition, so probably not of a work of language either—will ever be the same. The tempo and timbre of each will be distinct, let alone its deeper resonance, build, and thrust. So there may always be room for one translation more, especially as idioms and eras change, and I thank the following friends for suggesting that I try my hand at Virgil: André Aciman, Christopher Davis, James Dickey, Charles Gillispie, Shirley Hazzard, Christopher Hedges, Robert Hollander, John McPhee, Jeffrey Perl, Theodore Weiss, and Theodore Ziolkowski.

I have been especially fortunate in finding readers for the work in progress. First the classicists. Robert Kaster went through books 1, 4, 6, 10, and 11 in considerable detail; Denis Feeney generously did the same—amid a demanding chairmanship—throughout the entire poem; and the late Douglas Knight, having worked through the first four books with me, no sooner saw Dido out of this world than he followed her himself. And then there were the writers, Edmund Keeley, Chang-rae Lee, J. D. McClatchy, Paul Muldoon, and C. K. Williams with Catherine Mauger. Each has read my drafts with sharp eyes and open minds and a tireless fellow feeling. They have looked a gift horse in the mouth, as Robert Graves once said to a would-be writer, and prescribed the dentistry it needed.

I would also thank the friends who asked me to read the work in public and perhaps improve it in the bargain. First my hosts at Princeton University, who invited me to their classes, their colloquia and other con venings—Sandra Bermann, Andrew Feldherr, Brooke Holmes, Nancy Malkiel, Susan Taylor, and Michael Wood. Then Robert Goheen at the Wistar Association, Karl Kirchwey at Bryn Mawr College, and Rosanna Warren and Steven Shankman at the Association of Literary Scholars and Critics.

The roofs of some great houses have extended welcome shelter to the translator and his work. My thanks to Mary and Theodore Cross for turning Nantucket into Rome West with their Virgilian hospitality. And my thanks to the house of Viking Penguin that has produced the book at hand. My editor, Kathryn Court, assisted by Alexis Washam, once again has treated the writer and the writing too with insight, affection, and address. My senior development editor has been Beena Kamlani, and once again her efforts to tame and train a fairly unruly piece of work have been heroic. And all the good people at Viking Penguin—Susan Petersen Kennedy, Clare Ferraro, Paul Slovak, Paul Buckley, Leigh Butler, Mau reen Donnelly, Francesca Belanger, Florence Eichin, John Fagan, Matt Giar ratano, Dan Lundy, Patti Pirooz, John McElroy, Nancy Sheppard—all have been loyal allies in New York, joined by Adam Freudenheim and Simon Winder in London. And through it all, without the unfailing strategies and support of my friend and agent Georges Borchardt, assisted by DeAnna Heindel and Jonathan Zev Berman in turn, this translation might not have seen the light.

In closing, I thank the familiar spirits of Anne and Adam Parry, dear ghosts who pour the wine and lead the way. And first and last, my abiding thanks to Lynne, the Muse, and to our daughters, Katya and Nina, their husbands and their children. They have borne me through the work with the power of their love.

R. F.

Princeton, N. J.

Thanksgiving 2005

Thanksgiving 2005

THE ROYAL HOUSES OF GREECE AND TROY

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING

I. Texts and Commentaries

Austin, R. G., ed.,

P. Vergili Maronis Aeneidos Liber Quartus

(Oxford, 1955).

P. Vergili Maronis Aeneidos Liber Quartus

(Oxford, 1955).

———, ed.,

P. Vergili Maronis Aeneidos Liber Secundus

(Oxford, 1964).

P. Vergili Maronis Aeneidos Liber Secundus

(Oxford, 1964).

———, ed.,

P. Vergili Maronis Aeneidos Liber Primus

(Oxford, 1971).

P. Vergili Maronis Aeneidos Liber Primus

(Oxford, 1971).

———, ed.,

P. Vergili Maronis Aeneidos Liber Sextus

(Oxford, 1977).

P. Vergili Maronis Aeneidos Liber Sextus

(Oxford, 1977).

Conington, J., H. Nettleship, and F. Haverfield, eds. with commentary,

The Works of Virgil,

3 vols. (Oxford, 1858-83; repr. Hildesheim, 1963).

The Works of Virgil,

3 vols. (Oxford, 1858-83; repr. Hildesheim, 1963).

Eden, P. T., ed.,

A Commentary on Virgil Aeneid VIII

(Leiden, 1975).

A Commentary on Virgil Aeneid VIII

(Leiden, 1975).

Fairclough, H. R., ed. and trans., 2 vols.

Virgil

: vol. 1:

Eclogues, Georgics, Aeneid I-VI

(Cambridge, 1916); vol. 2:

Aeneid VII-XII. Appendix Vergiliana

(Cambridge, 1918); rev. by G. P. Goold (Cambridge, 1999, 2000).

Virgil

: vol. 1:

Eclogues, Georgics, Aeneid I-VI

(Cambridge, 1916); vol. 2:

Aeneid VII-XII. Appendix Vergiliana

(Cambridge, 1918); rev. by G. P. Goold (Cambridge, 1999, 2000).

Fordyce, C. J., ed.,

P. Vergili Maronis Aeneidos Libri VII-VIII

(Oxford, 1977). Gransden, K. W., ed.,

Virgil Aeneid Book VIII

(Cambridge, 1976).

P. Vergili Maronis Aeneidos Libri VII-VIII

(Oxford, 1977). Gransden, K. W., ed.,

Virgil Aeneid Book VIII

(Cambridge, 1976).

———, ed.,

Virgil Aeneid Book XI

(Cambridge, 1991).

Virgil Aeneid Book XI

(Cambridge, 1991).

Greenough, J. B., G. L. Kittredge, and Thornton Jenkins, eds.

Virgil and Other Latin Poets

(Boston, 1930).

Virgil and Other Latin Poets

(Boston, 1930).

Hardie, P., ed.,

Virgil Aeneid Book IX

(Cambridge, 1994).

Virgil Aeneid Book IX

(Cambridge, 1994).

Harrison, S. J., ed.,

Virgil Aeneid 10

(Oxford, 1991).

Virgil Aeneid 10

(Oxford, 1991).

Henry, J.,

Aeneidea, or Critical, Exegetical, and Aesthetical Remarks on the Aeneid

(London, Dublin, Edinburgh, Meissen, 1873-92; repr. New York, 1972).

Aeneidea, or Critical, Exegetical, and Aesthetical Remarks on the Aeneid

(London, Dublin, Edinburgh, Meissen, 1873-92; repr. New York, 1972).

Horsfall, N., ed.,

Virgil Aeneid 7

:

A Commentary

(Leiden, 2000).

Virgil Aeneid 7

:

A Commentary

(Leiden, 2000).

———, ed.,

Virgil Aeneid 11

:

A Commentary

(Leiden, 2004).

Virgil Aeneid 11

:

A Commentary

(Leiden, 2004).

Other books

Tiddly Jinx by Liz Schulte

The Cloud Pavilion by Laura Joh Rowland

Rough Draft by James W. Hall

The Revolution by Ron Paul

Spicy (Palate #1) by Wildwood, Octavia

The Woman He Married by Ford, Julie

Tough Guys Don't Dance by Norman Mailer

Taming Theresa by Melinda Peters

Sunrise with Seamonsters by Paul Theroux

Things We Left Unsaid by Zoya Pirzad