The Alchemy of Murder (15 page)

Read The Alchemy of Murder Online

Authors: Carol McCleary

“

Un bain

, Mademoiselle?

Mais bien sûr

! I’ll make the bath at five o’clock this afternoon,” the bath man says, quite obligingly.

“But I must have the bath this morning. I have a very important luncheon date.”

“Impossible, Mademoiselle, it requires time to prepare, but it’ll be superb, this bath.”

“Nothing is impossible.” And I slip him an extra two francs to prove it.

From a specialty store, I purchase muslin drawers, chemises, and a corset cover. I choose a used-clothing vendor for my outer garments because it will take too long to have clothes made. With adequate time I might be able to locate shops selling ready-made new clothes in a city the size of Paris, but my need is too urgent.

Fashion, of course, needs no translation. The French haute couture dominates fashion in both Europe and America, and a woman must stay aware of the current trend from Paris. I personally thank the gods that the horrid rear bustle is going out, but a whale-boned corset is required for a fashionable—but anatomically improbable—thin waist, something I refuse to wear. I don’t care if my waist is not nineteen niches. At least I can breathe.

I’m surprised to find the used goods are of very good quality.

“Cheap clothing wears out too quickly to be resold,” the shopkeeper tells me.

With little fuss I’m able to purchase a dark green suit of dense cheviot wool consisting of a jacket with a rolling collar and puffed sleeves and a full skirt of the same wool. Both garments are lined with black silk serge.

As a backup I buy a flared skirt of dark grey tweed, with two narrow bands of black braid near the hem. It’s a serviceable length for walking, just clearing the ground. A white waist shirt and simple black silk clubhouse tie, a tailored jacket of black wool, with long lapels and puff sleeves that gather at the top, complement the skirt. A hat of black lace covering a wire frame with a handsome bunch of silk flowers and pleated ribbon completes my clothing needs and suits my purpose perfectly—it has a Malines net veiling which I can hide behind when needed. Thank goodness I don’t need shoes. My black, high-top, laced walking shoes with low heels are quite satisfactory.

I gather up my purchases and make my way back up the hill to the garret.

* * *

“M

ADEMOISELLE

! Y

OUR BATH

!”

I just finished putting away my purchases when a pair of legs with a zinc bathtub on top of them appears at my door. How he made it up the narrow steps is a mystery. Another man behind him carries a cylinder of water and bathing accessories.

The tub is placed next to the potbellied stove and a white linen lining is adjusted. Sundry towels and a big bathing sheet, to wrap myself in after the ordeal, are miraculously produced. Then the process of filling the tub begins: two pails, two men, and countless trips down to a handcart that holds a heated tank of water. When it is half-full, hot coals are placed in a pull-out drawer underneath the tub.

The expense of three francs, which I figure to be about sixty cents, seems more than reasonable, considering the flight of stairs they had to endure, so I give them a generous tip. Arrangements are then made for them to pick up the tub in two hours.

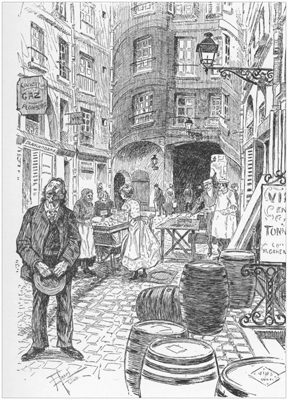

OUR COURTYARD

I can’t get into the tub fast enough.

I love soaking in hot bath water.

For me, it’s as close to heaven as I’ll get. Personally, I’ve never understood the great number of people who believe that regular bathing is unhealthy. Many Europeans don’t bathe fully more than a few times a year, relying instead upon sponge baths, and children often do not experience a full bath until their early teens.

I read an article in

Le Figaro

about an actress who boasted about having taken only two baths a year in order to protect her skin. She received a bar of soap on her birthday along with a note from a drama critic stating that the bar should last the rest of her life.

All too soon the tub men return and I prepare myself for my conquest of a famous man.

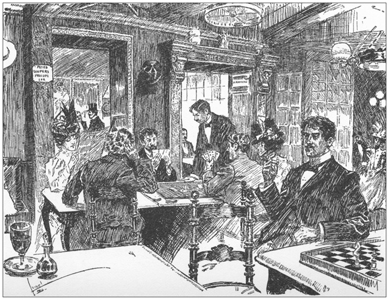

Café Procope is dimly lit with just a few oil lamps, as if the owner doesn’t want to let the world find its way in. I pause in the entryway, soaking in the atmosphere and the strong smell of

café noir

.

Founded a little over two hundred years ago by a Sicilian nobleman, Francesco Procopio dei Coltelli, the place is haunted by the ghosts of literary and political giants who breathed history into its walls.

Procopio provided a place where people of the arts—writers, poets, and philosophers—could work in peace and tranquility while sipping coffee, thus establishing the very first

café

in Paris, the French word for coffee.

In a city where cafés are notorious for blazing with light, noise, and glitter, the Procope maintains the modesty of a quainter and more illustrious age. One can image Ben Franklin, on whose death the café was draped in black, sitting under flickering candlelight, spies and informers lurking about, as he negotiated a secret treaty that would bring French soldiers and sailors to the aid of the colonies in their revolt against the British. Bonaparte, young and unknown, left his hat as security for payment of a drink, having left his pouch at home.

When I visited the café earlier to quietly observe my prey at his table, I was told that the table—topped with dark, reddish marble with pinkish, white veins—had been Voltaire’s; a man who prized clear thinking and crusaded against tyranny, bigotry, and cruelty while he drank coffee and argued about life, liberty, and happiness with Denis Diderot, the chief editor of the

Encyclopédie

more than a century ago.

The café staff must know who their distinguished guest is even though he has shaved his beard to hide his identity. The lack of beard provides anonymity and wipes years from his age. I believe he’s in his late fifties or perhaps early sixties, presenting a handsome maturity. At the moment he’s bent over sheets of foolscap, completely engrossed in his writing. A cup of coffee, a small bottle of vin rouge, hunks of bread, and a plate of cheese are positioned in a corner of the table.

I often find myself attracted to older men. My mother claims it’s because of the early loss of my distinguished father, whom I loved dearly. I also think my attraction to older men is because they know what they want in life.

The maitre d’ gives me a professional smile. “Table, Mademoiselle?”

“Please inform Monsieur Verne I wish to speak to him.”

His eyebrows arch. “

Pardon?

”

“Jules Verne, the gentleman at Voltaire’s table. Please tell him that Nellie Brown of New York wishes to speak to him.”

The man gets that insufferable look of contempt that only waiters in the greatest city in the world can affect. “I am afraid you are—”

“I know who the gentleman is. Please give him my message.” I slap my gloves impatiently in my palm and look him straight in the eyes. I have a great deal to do and have no time for pretense.

The maitre d’ leaves with a subtle, but intentional huff and huddles with Verne. The great man looks across the room at me. I meet his eye and give him a small nod and smile. More huddling occurs before the maitre d’ struts back to me. I start for Mr. Verne’s table and am stopped by a firm grip on my arm.

“I beg your pardon, Monsieur.”

With great delight the maitre d’ proclaims, “The gentleman does not wish to be disturbed.” He propels me to the door. “He suggests you flatter someone else with your unsolicited attentions.”

“You have no idea who—”

“My instructions from Monsieur are to call a gendarme and have you taken to Salpêtrière Hospital if you do not leave quietly.”

Salpêtrière! It’s a madhouse with no worse a reputation than Blackwell’s Island. For Mr. Verne to have threatened to have me institutionalized as if I were a crazy girl with romantic intentions is intolerable.

INTERIOR OF THE CAFÉ PROCOPE

“Tell Monsieur Verne he will regret not speaking to me about Gaston.”

I leave in a tempest rather than inviting the police.

To think that the man who wrote stories I thrilled to in my childhood would treat me so callously … he’ll pay, that promise I make to myself. When the time comes, Monsieur Verne will be at my feet begging for mercy.

As I flag down a fiacre, I chuckle without humor. In a sense I’ve already started getting my revenge. Wait till he finds out a likeness of him has been passed out on the streets connecting him to a mad killer. He will have a heart attack. I no longer feel guilt, I only hope I will have the entire Atlantic Ocean between us by the time the man discovers my machinations.

With that thought, I direct the cabby to take me to Pigalle Hospital.

I have the cab driver drop me a block from the hospital.

Pigalle Hospital is three stories of red brick and twelve pane windows. “Hospitals are only for the poor,” my mother said when I was a child. What she meant was that doctors usually come to one’s home. A doctor carries most of the tools of his trade in his black bag, so there is little a hospital has in the way of special equipment to offer a patient, unless one of the few surgeries offered are necessary. The poor and downtrodden end up crowded together in sick wards because they can’t afford home visits by a doctor.

As I approach the building on foot, I find myself hesitating. I lost my father at the age of six and it was a life-altering change for me. I watched a strong, healthy, wonderful man shrivel up and die within months and I couldn’t understand why and I hated everyone for letting God take him away from me. That was my first taste of death and I haven’t liked the flavor since.

* * *

A

CROWDED RECEPTION

area with an odor of sickness greets me. The large room looks like a shelter for the poor and homeless. Two harried male clerks—one younger and obviously new at the job because he keeps asking the older man for advice—tries to accommodate everyone with little success.

If I wait my turn I’ll be parked in the reception area for hours, surrounded by wrenching sickness and sorrow. I boldly cut through the crowd at the desk and in a firm voice demand, “Doctor Dubois?”

The older clerk doesn’t even look up from writing down a woman’s symptoms. He points down the hall. “Surgical ward. Grab a sponge.”

“Merci.” There’s no sense in asking him what the sponge is for, he’s gone back to his world of organized confusion.

The entrance to the surgical ward has large double-doors with a basin full of vinegar-smelling liquid and sponges next to them. The doors fly open and a nurse bolts out. She takes a sponge away from her face and drops it in the basin.

“Doctor Dubois?” I query.

She points behind her. “Down the corridor.”

The stench that escapes from the corridor when she opened the doors reveals why a vinegar sponge is necessary. I grab one and enter into a long, drab, empty hallway with doors on both sides.

I choose the third door on my right and flinch back as soon as I open it. Rows of beds fill the small room, with barely enough space to walk between them. There are three and four people to a bed, the feet of one to the head of another. In the bed closest to the door a pale child lies beside a grey-haired man who appears dead. The man’s eyes are wide open, staring straight up, never blinking, never moving while a fly is busy gathering something from his teeth. On the other side of the child lie a man burning in the delirium of fever. The fourth person is a man with a terrible disease of the skin; he tears at his skin with furious nails.