The Amazing Adventures of Phoenix Jones: And the Less Amazing Adventures of Some Other Real-Life Superheroes: An eSpecial From Riverhead Books (2 page)

Authors: Jon Ronson

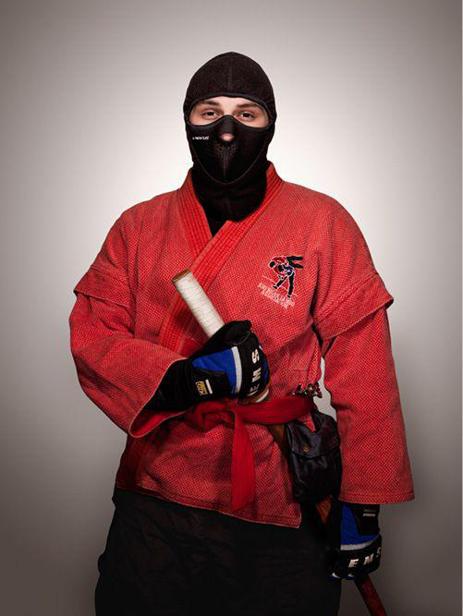

Red Dragon

They have a visitor—a superhero from Oregon named Knight Owl. He’s been fighting crime since January 2008 and is in town for an impending comic book convention. He’s tall, masked, and muscular, in his mid-twenties, and dressed in a black and yellow costume.

Knight Owl

They brief Phoenix on a group of crack addicts and dealers standing at a nearby bus stop. A plan is formed. They’ll just walk slowly past them to show who’s boss. No confrontation. Just a slow, intimidating walk past.

We spot the crack addicts right away. There’re ten of them. They’re huddled at the bus stop, looking old and wired, talking animatedly to each other about something. When they see us they stop talking and shoot us wary glances, wondering uneasily what the superheroes are covertly murmuring to each other.

This is what the superheroes are murmuring to each other:

KNIGHT OWL: “I’ve discovered a mask maker who does these really awesome owl masks. They’re made out of old gas masks.”

PHOENIX: “Like what Urban Avenger’s got?”

KNIGHT OWL: “Sort of, but owl-themed. I’m going to ask her if she’ll put my logo on it in brass.”

PHOENIX: “That’s awesome. By the way, I really like your black and yellow color scheme.”

KNIGHT OWL: “Thank you. I think the yellow really pops.”

PITCH BLACK: “I just want a straight-up black bandanna. I can’t find one for the life of me.”

PHOENIX: “You should cut up a black T-shirt.”

PITCH BLACK: “Hmm.”

Knight Owl, Phoenix Jones, and Red Dragon on patrol.

We’re ten feet from the bus stop now. Close-up these dealers and addicts look exhausted, burned-out.

“Leave them alone,” I think. “Haven’t they got enough to deal with? They’ll be gone by the time the daytime people arrive. Why can’t they have their hour at the bus stop? Plus, aren’t we prodding a hornet’s nest? Couldn’t this be like the Taco Incident times a thousand?”

The Taco Incident. Ever since Phoenix burst onto the scene some weeks ago with a short item on CNN extolling his acts of derring-do, the wider superhero community has been rife with grumbling. Many of the two hundred real-life superheroes out there, evidently jealous of Phoenix’s stunning rise, have been spreading rumors about him. The chief rumormongers have been New York City’s Dark Guardian and Washington State’s Mister Raven Blade. They say Phoenix is not as brave as he likes people to believe, and he’s in it for personal gain, and his presence on the streets only serves to escalate matters. For this last criticism they cite the Taco Incident.

“Tell me about the Taco Incident,” I ask Phoenix now.

He sighs. “It was a drunk driver. He was getting into his car so I tried to give him a taco and some water to sober him up. He didn’t want it. I kept insisting. He kept saying no. Eventually he got kind of violent. He tried to shove me. So I pulled out my Taser and I fired some warning shots off. Then the police showed up. . . .”

“I didn’t realize he was a drunk driver,” I said. “The other superheroes inferred it was just a regular, random guy you were trying to force a taco onto. But still”—I indicate the nearby crack dealers—“the Taco Incident surely demonstrates how things can inadvertently spiral.”

“They’re in my house,” he resolutely replies. “Any corner where people go—that’s my corner. And I’m going to defend it.”

We walk slowly through the drug dealers. Nothing happens. Everyone just stares at each other, muttering angrily. It is 5

am

. Our first night’s patrolling together ends. I’m glad, as I found the last part a little frightening. I am not a naturally confrontational person, and I still have all my luggage with me.

When I was growing up in the 1970s and devouring Batman comics, introverted geeks like me tended not to actually patrol the streets looking for crimes to thwart. We were the lame ones, running shrieking from real-life danger, cheering Batman vicariously on from our homes. How did all that change? How did my nerd successors get to be so brave?

The Real-Life Superhero Movement actually began, their folklore goes, all the way back in 1985, in Winter Park, Florida, when a young man (whose real-life identity is still a closely guarded secret) built himself a silver suit, called himself Master Legend, and stepped out onto the streets. He was an influential, if erratic, inspiration to those who followed.

“Ninety percent of us think Master Legend is crazy,” Phoenix Jones told me. “He’s always drinking. He believes he was born wearing a purple veil and has died three times. But he does great deeds of heroism. He once saw someone try to rape a girl and he beat the guy so severely he ended up in a hospital for almost a month. He’s an enigma.”

The rise of the mega–comic conventions has surely helped fuel the movement. I remember a friend, the film director Edgar Wright, returning from his first San Diego Comic Con, saucer-eyed with tales of hitherto reclusive geeks wandering around in immaculate homemade costumes, their heads held high.

“It was like Geek Pride,” he said.

But the community has really blossomed post 9/11 and especially during the recession of the past few years.

“It’s in the zeitgeist of our nation to help strangers in need,” says Phoenix’s friend Peter Tangen. “Many RLSHs [real-life superheroes] were raised learning morality from comic books and have applied that to their everyday lives. It’s our natural way of reacting to the challenges of the day.”

There’s no national convention or gathering, but Peter Tangen is doing all he can to make them a structured, self-respecting community, with a coherent online presence.

Peter’s origin story is as remarkable as any of the RLSHs’. He is by day a Hollywood studio photographer. He’s responsible for a great many of the instantly recognizable superhero movie posters—Tobey Maguire as Spider-Man, etc. But he’s always felt like a cog in the machine.

“I’m one of those guys that toils in obscurity,” he says. “Nobody knows my name because you don’t get credit on a movie poster.”

When he learned there were people doing in real life what the likes of Tobey Maguire only pretended to do on a film set, it unlocked something profound within him. So he approached them, offering to photograph them in heroic, unironic poses. His hope is to de-ridicule them—make them seem valiant, worthy of respect. The project has become Peter’s calling in life.

It is testament to Phoenix that most people had no idea their world existed until he came along. The CNN report praising his bravery has now had six hundred thousand YouTube hits. Something about him, and not the others, has captured the imagination. I hope to work out what that thing is.

The next morning I have coffee at a downtown Seattle café with Knight Owl.

“Last night might have been dangerous,” I tell him, sounding annoyed.

“We ruffled some feathers.” He nods. “When we walked past that bus stop there were people mumbling under their breath. It could have got out of control. I don’t think they would have gunned us down. But they may have taken potshots and run. Still, shots fired would have been a crime. It would have been attempted murder in my opinion.”

“Well, I’m glad none of that actually happened,” I say.

Knight Owl used to be a graphic designer. “There was no promotion potential. I simply existed. It was thankless. I wanted something more with my life.” So he joined the movement.

There is, he says, a bit of a superhero trajectory. When they start out they make rookie mistakes. Then they hit their stride. Then they not infrequently start to believe they have actual superpowers. Then they burn out and quit.

The first rookie mistake is to adopt a superhero name that’s already in use.

“It’s a general faux pas,” he says. “Anything with the words ‘Night,’ ‘Shadow,’ ‘Phantom,’ those dark, vigilante-type-sounding names tend to get snapped up pretty fast.”

“Have there been any other Knight Owls?” I ask.

“There was an Owl,” he says. “The Owl. But he ended up changing his name to Scar Heart, as he’d had a heart transplant.”

He says he chose his name before he knew there was a Nite Owl in the

Watchmen

comic, so when people online tell him, “You’re a fucking fag and by the way, Knight Owl’s taken—haven’t you seen the

Watchmen

?” they don’t know what they’re talking about.

The second rookie mistake is to “get caught up in the paraphernalia. People should think more about the functionality.”

“Capes clearly aren’t functional,” I say, “because they can get snagged on things. Is cape wearing a rookie mistake?”

“If you’re going to do some serious crime fighting there’d better be a good reason for a cape.” He nods. “And grappling hooks. No, no, no, no, no! What? You think you’re going to scale a building? What are you going to do when you get up there? Swoop down? Parachute down? You’re not going to have enough distance for the parachute to even open.”

Grappling hooks was one of Phoenix Jones’s rookie mistakes. He also had a net gun, but on one occasion it backfired and ensnared him and he fell on the floor and had to be cut loose by the police. So now he leaves it at home.

Then, at the other end of the trajectory, are the burnouts. I ask Knight Owl if he’s worried about Phoenix. Maybe he could become a burnout.

“I think he should take his doctor’s advice, rest up, get healthy, get strong,” he replies. “The way he’s going is a recipe for disaster.”

I talk to Phoenix on the phone. He’s frustrated that I never saw him engage in any proper crime fighting. I promise to stick around with him and give it another chance. He says a trip to the dangerous Seattle suburb of Belltown at 4

am

on a Saturday night should do the trick. We make a date.

Meanwhile . . .

. . . San Diego. Wednesday night.

I’ve been wanting to see another superhero operation at work to compare Phoenix with, so I’ve flown here to meet Mr Xtreme. He’s been patrolling most nights for the past four years, the last eight months with his protégé, Urban Avenger.

They pick me up at 9

pm

outside my hotel. Both are heavily costumed. Mr Xtreme is a thickset man—a security guard by day—wearing a green and black cape, a bulletproof vest, a green helmet and visor upon which fake eyes have been eerily painted. His outfit is covered with stickers of a woman’s face—Kitty Genovese. In March 1964, she was stabbed and seriously wounded in her doorway in Kew Gardens, Queens, New York. Her attacker ran away. During the next half hour thirty-eight bystanders saw her lying there and did nothing. Then her attacker returned and killed her. She has become, understandably, a talisman for the RLSH movement.