The Ancient Alien Question (35 page)

Read The Ancient Alien Question Online

Authors: Philip Coppens

Though this is a tremendous scientific discovery, the scientific community is largely unwilling to accept it. Until recently, scientists’ consensus view was that there

could

be extraterrestrial life, but if there was, it would be too distant for us to have active contact with it. In short, the answer to the Alien Question is

no

. They argued that the fabric of the universe—space-time—hindered beings from traveling over such vast interstellar distances. The problem is one of food, the human life span, fuel, and other rather mundane subjects that are nevertheless key ingredients. And with these objections, they feel that they can uphold their consensus view that We Are Alone.

We Are the Martians

Life on Earth is often found in the most unexpected places, from the deepest crevices of the oceans to the hottest walls of active volcanoes. Finding life in what we would consider to be an inhospitable environment, such as inside a meteor crashing to Earth, would therefore seem unlikely, but not impossible. Finding evidence of life inside a meteor would prove that life exists elsewhere in our solar system, thereby destroying scientific consensus that life is all about our Earth.

Richard Hoover, an astrobiologist at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama, has argued that filaments and other structures in rare meteorites appear to be microscopic fossils of extraterrestrial life that resemble algae known as cyanobacteria. He discovered these features after inspecting the freshly cleaved surfaces of three meteorites that are among the oldest in the solar system, one of which is the Orgueil meteorite, which crashed on May 14, 1864, near the French town of Peillerot. Some of the bacteria Hoover identified resemble bacteria found on Earth, though others looked less familiar. His findings suggest that some of the bacteria found here on Earth have extraterrestrial origins.

The best candidate for life in our solar system outside of Earth has always been Mars. In the early phases of our solar system, conditions on Mars and Earth were pretty similar, and it was only later on that Mars became the inhospitable place it is now. Though we have never been to Mars, Mars has come to us. We know that an estimated one billion tons of rock have traveled from Mars to Earth. We know that microbes have been shown to be capable of surviving traveling the distance between the two planets and the shock of an impact on our planet. If there was life on Mars, it certainly could have traveled to our planet riding on a meteorite.

Allan Hills 84001 (commonly abbreviated ALH 84001) is a meteorite that was found in Allan Hills, Antarctica, on December 27, 1984, and that in 1996 was made famous when Bill Clinton entered the White House Press Room to broke with business-as-usual and announced to the world that NASA had found evidence of life on Mars. The announcement came about as NASA scientist David McKay believed he had found microscopic fossils of Martian bacteria based on carbonate globules inside the meteorite. Since 1996, the issue of whether or not this particular meteorite contains evidence of extraterrestrial life

remains, to say it modestly, controversial, largely due to diverging scientific camps, showing once again that exobiology does not seem to be an exact science.

There are 34 meteorites on our planet currently catalogued as likely originating from Mars. Among these, two have been put forward as being on par with ALH 84001 when it comes to indications of Martian life. One of them, the Shergotty meteorite, fell to Earth at Shergotty, India, on August 25, 1865. Its interior is said to indicate the remnants of biofilm, and therefore could be evidence of the existence of microbial communities. The other candidate, the Nakhla meteorite, fell to Earth on June 28, 1911, near Alexandria, Egypt. Many people witnessed its explosion in the upper atmosphere before it fell to Earth in about 40 pieces. When analyzed, the Nakhla meteorite turned out to be the first Martian meteorite to show signs of aqueous processes. The meteorite contained carbonates and hydrous minerals, which are the result of chemical reactions in water. Scientists also learned that the rock had definitely been exposed to water, which proved that there was once water on Mars. There is further evidence of carbon inside some of its fragments, but the presence of carbon is insufficient to convince all scientists that bacteria once lived on Mars.

In recent years, the Mars orbiter and rover missions have shown that the Red Planet indeed once had abundant water. Though the surface of Mars today is too cold and dry to support known life-forms, there is evidence that liquid water may exist not far beneath the surface.

The odds are—once again—in favor of Mars once having had basic microbial life. But that is—unsurprisingly—not the scientific consensus. In order to settle the debate, a team of researchers at MIT and Harvard in 2011 developed an instrument that they hoped could provide the proof that life on Mars did once exist, and may have been responsible for life on planet Earth. The team of Christopher Carr and postdoctoral

associate Clarissa Lui, working together with Maria Zuber, head of MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS), and Gary Ruvkun, a molecular biologist at the Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard University, have created an instrument that should allow them to discover evidence of DNA or RNA. They have labeled their quest the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Genomes (SETG). Their instrument could take a sample of Martian soil from below the surface and process it to separate out any possible organisms and amplify their DNA or RNA, as well as use biochemical markers to search for signs of particular genetic sequences that are nearly universal among all known life-forms. Their hope is that, when it’s finished, their device will find a ride on a future exploration to the Red Planet.

If the device lifts off, it will become one of a very short list of instruments that have been sent to Mars to search for life. The first was launched in 1976 with the

Viking

Landers and produced ambiguous results. The most commonly accepted version of the 1976 tests is that they revealed no signs of life. But Gilbert Levin, the principal investigator of this project, felt that the conclusion was too quickly reached. In 1986, he reexamined the results and concluded that

Viking

may well have found evidence of microbial life on Mars.

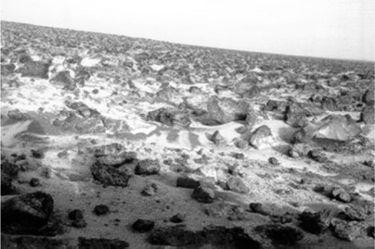

One image from the

Viking 2

Lander showed early morning frost at the landing site, offering further support that the planet once had water. But most importantly, one of the experiments was to detect metabolizing microorganisms. When the experiment was conducted on both the

Viking

Landers, it gave positive results! Yet despite the straightforward, positive result, the conclusions were debated away! Does anything more need to be said?

When probes landed on Mars, early experiments apparently showed that there was no life on the Red Planet. But since then, those results have been questioned. Together with evidence from meteorites, images like these, which show frost on the Martian surface in the morning, indicate Mars once was home to living organisms.

Alien Probes

Professor Chandra Wickramasinghe argues that after 1982, evidence for cosmic life and panspermia acquired a status close to irrefutable, but publication avenues that were hitherto readily available to its proponents became suddenly closed. He has gone on the record with his opinion that, after 1982, attitudes hardened to a point that panspermia and related issues were decreed taboo by all respectable journals and institutions. Nothing that challenged the scientific dogma of how life had originated on planet Earth could be published, in spite of the vast amount of scientific data showing that life did not originate here.

He adds, “Even though the general public reveled in ideas of extraterrestrial life, science was expected to shun this subject

no matter how strong the evidence, albeit through a conspiracy of silence. It was an unwritten doctrine of science that extraterrestrial life could not exist in our immediate vicinity, or, that if such life did exist, it could not have a connection with Earth.”

1

Wickramasinghe became evidence of this “conspiracy of silence” himself when in March 2010 he was dismissed from his post at Cardiff University’s Centre for Astrobiology, as funding was withdrawn from his department.

Wickramasinghe has gone far beyond the idea that life was seeded here on planet Earth; he argues that every day, alien life-forms enter our planet, in the form of flu viruses. He has found that outbreaks of the flu are often found to coincide with major meteor showers that sprinkle the Earth’s atmosphere with what is literally extraterrestrial material. Specifically, he believes that diseases such as the Spanish Flu virus actually rode to Earth from space on meteors, before it caused widespread death in 1918–20. Between 50 and 100 million people, or 8 to 16 percent of the world’s population, died from the Spanish Flu, making it one of the deadliest natural disasters in human history: some 550 million people, or 32 percent, were infected. Worst affected was Western Samoa, where 90 percent of the population was infected, and one-third of adult men, one-fifth of adult women, and one tenth of all children were killed.

The lethal second wave covered almost the entire world in a very short period of time, suggesting that the speed at which it traveled was beyond a human carrier, and that the virus was literally seeded from space. Lau Weinstein observed that “Although person-to-person spread occurred in local areas, the disease appeared on the same day in widely separated parts of the world on the one hand, but, on the other, took days to weeks to spread relatively short distances.”

2

The best evidence for its extraterrestrial delivery mechanism was that in the winter of 1918, the disease suddenly appeared in Alaska, in villages that had been isolated for several months.

Wickramasinghe also points to the Plague of Athens and the Plague of Justinian as two further examples of plagues that might have had alien origins. The Plague of Athens was a devastating epidemic that hit the Greek capital during the second year of the Peloponnesian War (430

BC

). The cause of the plague remains unknown. The Plague of Justinian afflicted the Byzantine Empire, including its capital Constantinople, in the years

AD

541–542. It was one of the greatest plagues in history. Wickramasinghe includes the more recent SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) outbreak as having potential extraterrestrial components. SARS created a near pandemic, between November 2002 and July 2003, with 8,422 known infected cases and 916 confirmed human deaths. Within a matter of weeks, SARS had spread from the Hong Kong province of China to 37 countries around the world. Microbes have been identified in the upper atmosphere, and though it is known that storms, monsoons, and volcanic activity can transport them to these regions, the mesosphere is also the first region where meteors begin to fragment.

The evidence accumulated so far suggests that the worst flu epidemics coincide with peaks in the 11-year cycle of sunspot activity, and this was once again the case in 2000. Removing Wickramasinghe from his position has not helped him find more evidence for this possibility. He points out that as much as a ton of bacterial material might fall to Earth from space daily, which translates into some 1,019 bacteria, or 20,000 bacteria per square meter of the Earth’s surface. This is an astonishing amount of material. Most of it simply adds to the unculturable or uncultured microbial flora present on Earth. But in some cases, this bacterial material turns against nature, and leads to death and destruction. Just as life came from elsewhere, death, too, is sometimes an alien invader.

Wickramasinghe also argues that our ancestors drew the same conclusions he has drawn. Ancient Chinese astronomers

chronicled numerous episodes when the apparition of comets preceded plague and disaster. The Mawangdui Silk, compiled in 300

BC

, details 29 different cometary forms and the various disasters associated with them, dating as far back as 1500

BC

. Wickramasinghe concludes, “All ancient civilizations, without exception, have looked upon comets with a sense of trepidation and awe. Comets were considered to be harbingers of doom, disease, and death, infecting men with a blood lust to war, contaminating crops, and dispersing disease and plague.... The views of ancient civilizations—the Chinese, Egyptians and Indians—that laid the foundations of philosophy and science, including astronomy, should not be so easily dismissed.”

3

And so we have almost come full circle, for it was with the original proponent of panspermia that we saw the drive to remove mythology from “the scientific approach.” The current billboard of the theory of panspermia is suggesting we once again allow legends, myths, and ancient accounts to be included in the debate.

Other books

The Double Rose by Valle, Lynne Erickson

Farm Boy by Michael Morpurgo

Anna Maria Island by O'Donnell, Jennifer

Trace (TraceWorld Book 1) by Letitia L. Moffitt

Sin and Sensibility by Suzanne Enoch

Amo del espacio by Fredric Brown

Second Chance by Chet Williamson

Endangered (9781101559017) by Beason, Pamela

Threshold by Sara Douglass

Odin's Shadow (Sons Of Odin Book 1) (9th Century Viking Romance) by Erin S. Riley