The Angry Planet (11 page)

Authors: John Keir Cross

“Who are you? Who are you? What

are you doing here?”

VI. THE MEN OF MARS by Stephen Macfarlane

THE NARRATIVE CONTINUED, BY STEPHEN MacFARLANE: THE MEN OF MARS

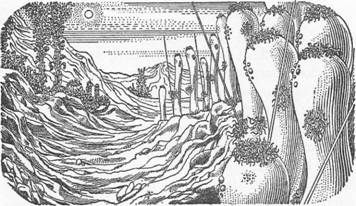

WE ROSE to our feet. Jacky

moved over towards me, and I put my hand on her shoulder to allay her

nervousness. We were all nervous. Why should we not be?—there was something

unutterably awesome in the very quietness and immobility of the two-score odd

creatures above and all around us. How long had they been standing there,

gazing down at us while we slept? The vast plain had been empty—now, from

nowhere seemingly, these beings had appeared, creeping unerringly to the one

hollow among all the hollows in that expanse that held a secret.

What did they look like?—what

was our first impression of them? It is difficult to say. Since that first day,

I have known them so intimately, have studied them at such close quarters, that

I can hardly remember how they first seemed to present themselves.

There was nothing, in the whole

range of our experience of living beings on earth, to which they could quite be

compared, although in general shape they were not unlike human beings. They

were small, varying in height from 4 to 5 feet—their leader, to whom I have

already referred as the tallest, was about 5 feet 6 inches. Their bodies were

slender, smooth and round; in general dimensions comparable to the trunk of a

medium-sized silver birch on earth. In color they were, in general, yellowish—a

dark, patchy yellow ochre; but this deepened to green towards the foot in most

cases, and sometimes merged to a fleshy pink and even red at the top. At the

top, this trunk of theirs, as I have called it, bulbed out slightly into a head

(I am, in this description, forced to use analogous human terms—“head,” “trunk,”

“hands,” and so on; but, as you will see later, the Martians are quite

different from us—the words are used only as equivalents, for the purpose of

building up some sort of image, however imperfect, in your minds). This “head”

was covered, on the rounded top, with a sudden fringe—a sort of crown—of small

soft tufts of a vivid bright yellow color. Just below this, on the front—the “face”

(although strictly speaking the Martians, as we decided later, had no faces—or

rather, their faces were these tufts or crowns on the top that I have

described)—there were three, sometimes four, sometimes even five, small

jellyish bulbs

—

glaucous protuberances which glowed transparently. These were

the eyes. There were no organs of hearing or smell—at least, in that first

glimpse we could see nothing that might be an ear or a nose; we found out

later, as we shall describe, that the Martians had a very highly-developed

sense of smell, although they could only “hear” sounds of considerable

loudness.

I now come to describe the “feet”

and “hands” of the Martians. At the lower extremity of the trunk—the greenish

part I have mentioned—the body suddenly bifurcated. Each of the forks split

again almost immediately, and so on and so on, so that on the ground, at the

foot of each figure, there was a perfect writhing mass of small, hard, fibrous

tentacles. About a third of the way up the trunk, in the front, there was

another sudden branching of similar “tendrils,” as I might call them—only these

ones were longer and lighter in color and seemingly more sensitive. These were

obviously the “hands,” since they held, in their twining grasp, the Martian

weapons—long spears, or swords, of some bright transparent crystalline

substance—a sort of flinty glass, as it seemed. Finally, to complete this

sketch of the appearance of the Martians, there were, just under the bulb of

the head, and on each side of the trunk, two smaller clusters of tentacles (or “tendrils,”

as I really prefer to call them). These were very short and slender, and light

green, almost white in color—like small pale sea anemones.

These, then, were the creatures

that confronted us that first morning on Mars. The task of describing them

properly has been almost impossible—as I say, I have had to use human terms—we

think, us men, almost always in terms of ourselves (“anthropomorphically,” as

Mac would say—a monstrous big word meaning, quite simply, just that—thinking of

everything, the whole universe, in terms of ourselves, as being

like

ourselves). The Martians were quite, quite different from ourselves—it was not

till we grasped that that we began to understand them. As our story goes on,

and you begin to learn more about these strange creatures of another planet,

perhaps you will be able to form a clearer picture of them than I have been able

to give in the brief sketch above.

The thing that astonished and

unnerved us most, however, at that first meeting with the Martians, was not so

much their appearance, strange as that was. It was the fact that the leader was

addressing us, and that the language he was using was our own English, as I

have said already at the end of the previous chapter.

“Who are you?” he said

distinctly. “Who are you? What are you doing here?”

I looked wildly at Mac—it

seemed, at any incomprehensible moment of our whole adventure, the only thing

to do; he was the wisest of our party—a Doctor of Philosophy, no less; if

anything was understandable, he surely could understand it—if he did not, what

chance had we?

Mac, alone among us, seemed to

have recovered some of his composure. He looked up at the leader of the

Martians and said, in a clear slow voice:

“We are men. We come from

earth.”

There was a rustling round the

top of the ridge—a mercurial quivering of those hundreds of white, wormy tendrils.

And the response came immediately—seemingly from several of the Martians at the

same time—in the chill, detached tones:

“What are men? What is earth?

Explain, explain, explain. Who are you? Where do you come from? What are you

doing here?”

The terrifying thing was that I

could not see anything in the way of a mouth on the creatures. How were they

talking at all, let alone talking in English? Where was the sound coming from?

And yet I knew, in my bones, that there was no sound—that I was not hearing

what the Martians said! The sensation was exactly the same as that that we had

experienced when Mac cut into the huge cactus-like plant on the plain, and a

scream seemed to come

into our heads.

I remembered what Jacky had said

on that occasion—it was as if we were

thinking

the sound rather than

hearing it. Now it was as if I were

thinking

these cold, detached,

insistent questions—they were forming of their own accord in my brain! It was

an uncanny experience—it was impossible not to feel uncomfortable and a little

terrified. Jacky shivered at my side—I could see that the boys’ faces were pale

and strained.

“Mac,” I cried, “for heaven’s

sake what is it? How are they speaking to us?—how in the Lord’s name can they

be speaking to us?”

He was curiously calm—when I

look back I always think of this as Mac’s best moment throughout our whole

adventure. He was, on earth, a quiet, reticent, scholarly man—the last man to

possess, in any marked degree, courage as we have come to define it. But

courage he did have—courage within his own terms of reference: the courage of

brains, of sheer intellect—he confronted the incomprehensible with his own

weapons, his brains. And he was confident in the possession of those weapons,

and in their efficiency—he was confident and cool in the face of this strange

enigma now, standing with one hand loosely on the pistol at his belt, the other

raised to shade his eyes from the sun as he gazed up at the Martian leader.

Without shifting this gaze for

a moment, he now answered me.

“I don’t know, Steve,” he said

quietly. “I do have a glimmering notion—no more than that yet. Give me time—just

a little longer.”

Then he raised his voice again,

and addressed the Martian in the same loud clear tones as before.

“Before I explain further who

we are,” he cried, “tell me who you are.”

Again the rustling and the

quivering, and again the response:

“We are the Beautiful People.”

Quick as a flash, Mac turned

round to us.

“Tell me, Steve—what did they

say?” he asked.

“Why—‘We are the Beautiful

People,’ ” I answered dazedly.

“And you, Jacqueline—tell me

what you heard them saying.”

“I thought they said—‘We are

the Lovely Ones,’ ” said Jacky timidly.

“Ah! And you, Paul?”

“I agree with Jacky,” said

Paul.

“So do I,” volunteered Mike. “That’s

what I heard them say—‘We are the Lovely Ones.’ ”

Mac smiled.

“Steve,” he cried, “I believe I’ve

got it. Watch this

—

I’m going to ask them a question—I’m going to ask them if they

knew we were here or if they came on us accidentally.

And you won’t hear me

saying a word.

Watch.”

There was a silence while he

gazed up at the Martian leader, with a curiously tense expression on his face.

Presently there was the usual quivering among the Martians, and there floated

into my head:

“Yes. We knew you were here. We

were told. We had a message.”

“I was right, Steve!” cried Mac

immediately, to me. “I know what it is! Try it yourself—look at that big

fellow, the leader—ask him a question. But don’t say anything—

think

it

to him, in your head—think it as hard as you can—put all your powers of

concentration into it.”

I did as he told me. I stared

at the Martian leader and thought, in my head:

“How did you know we were here?

Who gave you the message?”

There was no quiver—no

response.

“You’re not thinking hard

enough, Steve—you’re probably a bit nervous,” said Mac. “Make an effort—

throw

your thought towards him.”

I tried to calm myself, and

repeated the mental question with more concentration. And this time the

response came back:

“We were told by our friends

the Plants, whom you injured.”

I stared at Mac helplessly—the

whole thing was too much for me. Apart from the uncanny business of the

conversations, this latest response—that the Plants had told the Martians of

our presence—was bizarre and incredible. But Mac, far from seeming as baffled

as I was, was actually smiling triumphantly.

“Steve, it’s magnificent!” he

cried. “Who would ever have thought it! It’s so simple, man—don’t you

understand?—it’s

thought

transference! It isn’t speaking at all, as we

understand it—it’s pure communication—what scientists back on earth have been

arguing about and experimenting with for years. These creatures have got it

highly developed—they can plainly communicate with each other by simply

thinking a thought and so projecting it. That’s how they can speak to us—we

receive the thoughts they project—and of course, we receive them in the form we

are accustomed to think in—in our case English. I got the final clue when you

said you heard them say ‘Beautiful People,’ while Jacqueline claimed they said ‘Lovely

Ones.’ You were both right—the thought is the same in both cases. ‘Lovely’ is

probably a word that Jacqueline and the boys use more frequently than ‘Beautiful,’

which is a literary word, natural to a writer like you. If a Frenchman had been

with us, he would have claimed that the Martian said: ‘Nous sommes les Beaux.’

If my old rival Kalkenbrenner were here (and I bet he wishes he was!) he would

have heard the thought in his own native language of German: ‘Wir sind die Schoenen

Leute.’ It’s the pure thought we receive—we translate it in our heads into

whatever language or form of language we’re accustomed to.”

“But, Mac,” I protested, “it’s

fantastic—it’s unholy! Does that mean they’re listening-in now up there to all

this conversation of ours—these ideas that are flying to and fro between us in

the form of language?”