The Art and Craft of Coffee (6 page)

Read The Art and Craft of Coffee Online

Authors: Kevin Sinnott

2 SELECTING COFFEE BEANS

IN CHAPTER 1

we learned that although most commercial coffee sells as branded blends from the beans of many countries, upscale coffee tends to have a single country of origin (such as Guatemala or Ethiopia). The higher the price and the more unique the taste, the greater the likelihood of regions within a country (such as Sumatra’s Mandheling) or individual estates or farms (such as Costa Rica’s La Manita) selling their own coffee.

Thanks to Internet commerce and global shipping, it is conceivable that someone in the United States could purchase online a single-origin coffee grown on a plot in the Guatemalan mountains. Just a short time ago, such point-to-point individuality and identity tracking could only be imagined.

For practical purposes, we devote this chapter to bean freshness. By the end, you will know how to do the following:

• Identify and evaluate the best, freshest coffees, and choose the best one for you

• Taste coffee

• Differentiate blends and formulate your own personal blend

• Host a coffee cupping

Coffee Characteristics

Coffee is such a delicate fruit that almost any difference in where and how it’s grown, picked, graded, sorted, processed, packaged, and shipped—even its botanical DNA—seems to make a marked difference in how it tastes in your cup. Understanding these differences is essential for learning how to choose the best beans, whether already roasted or those you plan to roast yourself.

Species

Several coffee plant species fall under the Rubiaceae family, genus name

Coffea

. Arabica is the original cultivated plant species and the one that offers the finest potential flavor. Two others, Robusta and Liberica, are used commercially but primarily in commodity coffee. (See

chapter 1

, “Knowing Your Coffee Beans,” page 11 for a complete list of species, subspecies, and descriptions.)

Terroir

The earth in which the coffee trees are planted makes a big difference in a bean’s flavor. As gardeners know, soil feeds the plants, so coffee grown in different soil absorbs different nutrients. (It is similar to how grain-fed chicken or grass-fed cattle produce meat with different flavors than their commercial counterparts.) Jamaica’s rich volcanic soil produces different tasting coffee than chalky or sandy Yemen soils even if the beans come from the same parent trees.

Climate

Rainfall, sunlight, temperature, and other environmental factors all affect how beans grow and taste. A region’s particular climate influences season length, speed of bean-ripening, and water’s role as a nutrient. For example, coffee grown in thinner mountain air ripens later. Cloudy skies, tall trees, and mountains each form a canopy that protects beans from harsh sunlight.

Farming Standards

A number of farming techniques nurture coffee beans into realizing their full potential. Soil fertilization, pruning, watering, and other tree care change the soil’s ability to feed the trees. For example, contoured soil ensures equal distribution of water among trees.

Farmers must harvest beans at their peak ripeness to ensure a top-quality crop. This means picking coffee several times during the month so that beans are ripe. A single picking means some beans will be under-ripe; others will be over-ripe. Harvesting a tree’s beans en masse—ripe, under-ripe, and all—compromises the coffee’s quality. Also, coffee trees only produce quality beans through so many harvests, meaning a properly managed farm replants its trees regularly.

Beloved Sumatra cherries and green beans, side by side.

Processing

The fruit of the coffee tree looks much like cherries—round and fleshy with a large seed pit. To make coffee, these seeds must be removed from the trees and dried. How and how well this happens affects flavor. There are two methods of processing: dry and wet.

Dry processing is the original method still practiced in many regions worldwide, particularly near coffee’s Ethiopian birthplace. In this process, picked cherries dry out on a sun-exposed surface, such as a flat rooftop, causing the skin and fruit to become brittle and easy to remove. Layering beans is fine, as long as they get turned regularly to avoid scorched top layers and moldy bottom layers. Skin removal requires skill and good judgment; if too much skin gets peeled, the beans lose a layer of protection, potentially allowing premature staleness or mold. Most, if not all, of the dry process happens by hand.

The dry process likely presents the purest representation of a coffee bean and its terroir, offering nothing but the bean’s flavor as nature grew it. Dry processing also offers more viscosity, mouth feel, body, depth, muted acidity, and potentially earthy flavors, and it requires less water—particularly important in climates with barely enough for human consumption. But the process is quite time-consuming and labor-intensive.

In wet processing, coffee cherries soften in large vats of water. A machine then mechanically removes the seeds: the soft fruit peels away and floats as the seeds (beans) sink to the bottom. The flesh gets discarded or composted. The seeds are then dried using either the natural, old-fashioned sun method or in mechanical dryers. With the latter, beans can dry out too much if not watched carefully, and then cracking can make them vulnerable to mold formation. Once dried, they are hulled, mechanically or by hand, and the skins removed not much past the outer protective coating.

Wet processing offers brighter acidity and an arguably cleaner, less earthy taste due to quicker skin removal. But it involves water, adding the risk of mold formation.

Storage and Shipping

Coffee beans are like sponges that easily pick up off-tastes and odors. Climate during transit and warehousing also affect flavor. For example, beans stored in high humidity can ferment or rot. Beans stored in any environment for an extended period lose flavor.

Beans have long been shipped in sacks made of jute (or burlap), which are economical and practical for handling but expose beans to moisture, air, and odors during their shipping. Water shipment, still the standard coffee bean transport method, means long sea voyages, exposure to moisture for extended periods of time, and storage next to all manner of products, some inert and others not. Once a shipment of coffee arrives in port, it can get damaged if not properly stored.

Roast

Different roasts make otherwise identical beans taste completely different. Roasting is such an essential, complex component of a bean’s flavor that we’ve devoted

chapter 3

entirely to it.

An assortment of raw green coffee beans ready for roasting.

Green Coffee Bean Basics

In a perfect world, the best coffee beans grow in rich earth, protected from harsh sunlight, and get picked by farmers who choose the exact moment of ripeness, carefully remove the beans, and then ship them to us. Or would that actually be perfect? For every common-sense agricultural rule, there’s a coffee example to defy it. Those rule-breaking coffees are often among the finest.

Take Yemen Mocha, for example. Often, the coffee cherries appear as dry as raisins while growing. They receive far too much sunlight and Yemen’s arid climate robs them of any but an occasional watering. They grow practically at sea level, a far cry from choice high-altitude mountains. They dry on rooftops, mostly because farmers there are far too poor and live in such a water-scarce region that they cannot consider using even the most primitive water hull-removal equipment.

So are there no rules? The best we have are centuries’ worth of trials and errors from each region. Though not hard and fast, the tips that follow at least provide some quality predictors to make us better buyers.

Buying Beans in Season

Coffee flavor is a constantly moving target. Like a flower, coffee can lose its scent seemingly in an instant. To make sure the coffee tastes its best, use it quickly. That means drinking what’s in season, which requires knowing when various coffee-growing regions plant and harvest their crops.

Think about what season it is right now. Like most crops, coffee requires time from its initial budding until the beans ripen for harvesting. Some countries such as Guatemala have just one annual harvest because of their dramatic wet and dry seasons. Others with more consistent climates such as Ethiopia harvest multiple times throughout the year. A country such as Brazil, with its giant, industrial approach to coffee and consistent weather, harvests year-round. Most countries have one or two harvests annually.

Within a given region, not all beans ripen simultaneously. One farm at higher altitude that experiences dry conditions may harvest its coffee a month later than others in the area. The beans on a farm with greater sun exposure may ripen earlier than one shaded by trees or a mountain. Often, the earlier ripening and picked coffees are lower quality. In the coffee industry, here’s the rule of thumb: Middle-arriving beans are the best. Of course, as in all things coffee, there’s an asterisk. Coffee pickers, typically paid by their yield and not for their discernment, may pick unripe or past-prime cherries to earn more money. Beans are simply more plentiful at the early and late stages of the season.

Green coffee, like roasted coffee, can go stale. So regardless of harvest time quality range, it’s wise to buy green coffees six weeks after harvest to allow for processing and shipment. Beans available earlier, sometimes called new crop beans, likely come from the lowest elevation. Coffees bought late in the season may have lost flavor, either from over-ripeness, inadequate or improper storage before processing, or flavor loss due to warehousing after processing. Exceptions to this are the so-called aged coffees, green beans specially stored in climate-controlled conditions so they can soften, or lose acidity.

Once you purchase green beans, you have a second roughly six-week window to roast them at their peak.

AGAIN GRACEFULLY

When properly controlled and when used in blends or as single origins, the aged effect offers qualities prized by the coffee connoisseur. However, I caution the novice who attempts to purchase aged coffee. It’s a fine line line between aged and old. The allure of green beans labeled “aged” has fooled even the most veteran coffee buyers.

Colombia, Venezuela, Sumatra, Java, and India sometimes offer aged coffees. India’s Monsoon Malabar is named for its storage through the monsoon season, which reportedly subjects it to unusual conditions and creates a strong flavor you either love or hate.

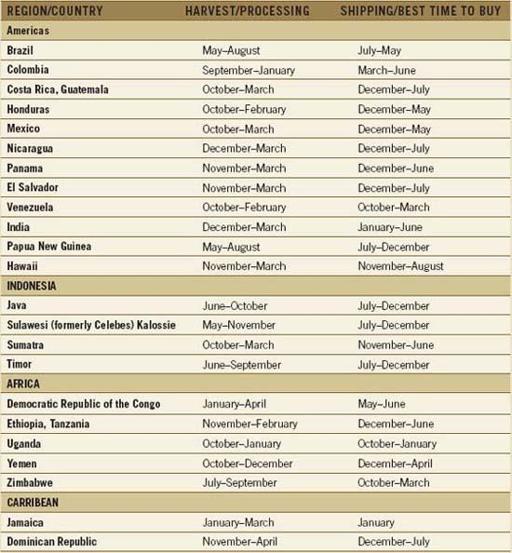

Global Coffee Harvests

This chart lists several coffee-growing regions and their harvest times, followed by approximate dates for shipping each season’s coffee crop. Most of the Northern Hemisphere’s peak harvest time is between December and March. Most of the Southern Hemisphere’s peak harvest time is from May through September. (6–8 weeks shipping time implies market availability.