The Art of Holding On and Letting Go (3 page)

Read The Art of Holding On and Letting Go Online

Authors: Kristin Lenz

I coiled my body, forearms pulled, legs extended. I was weightless. Gravity had no power in this instant, this one second of free-momentum hovering in the air. I grasped the edge of a shallow bucket and swung my leg to the side, heel-hooking a curved edge. I clipped the bolt and breathed.

A droplet of sweat rolled down the back of my neck. The massive overhang loomed above my head. I reached up and curled two fingers over the lip of a tiny pocket carved into the wall.

A flash of heat washed over me like a wave. Blood pulsed in my temples. The ceiling of the overhang undulated in the glaring sunlight. A roar of darkness flooded my peripheral vision.

Down was up; sky was ground. Breath sucked out of my lungs. Throat parched. Core clenched. Biceps flexed. Knuckles whitening.

My fingers no longer belonged to my body. They slipped, skin scraping.

One millisecond of weightless freedom.

Gravity wrapped its hand around my ankle and yanked. My stomach plummeted. The rope pulled taut, arresting my free-fall with a jerk. The crowd gasped below me. I swung and slammed into the climbing wall.

I sat on the ground, head lowered, knees pulled in to my chest. The sun beat down on the back of my neck.

Coach Mel plunked down beside me. “What happened?”

I didn't answer.

“After you pulled off that dyno, I thought you had it made.”

I shook my head. My sweat-soaked top stuck to my back.

“How's your wrist? Did it give out on you?”

My left wrist was wrapped with white tape. I extended my arm and rotated my hand. “It feels fine.” I flexed my fingers; the first two were bloody at the tips.

She winced. “Ouch.”

My right wrist was bare. I had debated wearing the tagua bracelet that morning, but was afraid it would scrape on the climbing wall and break. I wasn't one to be superstitious, but now I wondered.

Coach Mel lifted her eyes to the top of the climbing wall as the crowd hooted and clapped, and I followed her gaze. A French climber had finished the route. She'd advance to the finals tomorrow.

“I'm afraid you're out of the running now, unless someone else falls,” Coach Mel said. She turned to look at me. “It's like something spooked you up there. You sure you're feeling all right?”

I nodded, then shook my head.

Becky passed by and patted me on the head. “Sorry, I guess it happens to all of us.”

I flinched. It hadn't been an ordinary fall. I hadn't miscalculated a move, my muscles weren't pushed to exhaustion. I had been balanced on the wall with a firm grip. And then it was like the earth tilted, and I wasn't even sure where I was. As if something had gone terribly wrong with the world; I felt it deep in my core.

“Keep drinking,” Coach Mel said with a nod toward my water bottle. “Do you feel faint? Do you need to eat?”

I needed to sip my warm herbal tea, breathe the scent deep into my lungs, deep into my muscles. I had checked the lost and found and searched all around the competition area for my thermos, but it was still lost.

“You're worried about your parents.”

I met her eyes, trying to read her expression. What did she know?

“They're not due back until later this evening, right? And they said not to worry if they were late.” Her gaze was steady, confident. “I'm sure they're fine.”

But deep down in some hidden, dark corner of my body, a raw fear was growing like nothing I had ever felt before, a physical sensation clawing through my veins.

The French climber waved and blew kisses to the crowd. I dropped my head onto my knees.

We were silent, watching the next competitors climb the route. A Japanese girl reached the overhang, looked up, and paused. My stomach quivered for her.

She crouched and tried to dyno over the crux. She soared off the wall.

Coach Mel whipped around to look at me. “That's the exact same hold you slipped off.”

Incredibly, the next two climbers stopped and crouched beneath the overhang, then fell, swinging on the rope. My eyes were wide. That spot on the wall was cursed.

Coach Mel grinned. “I guess you're not out of the running after all.”

I nodded, but I was climbing on Mount Chimborazo with my parents and Uncle Max, guiding them safely down the mountain. I was scanning the crowd, waiting for Mom and Dad to rush toward me with sweeping hugs. I wouldn't even feel embarrassed if Dad picked me up and swung me around. I wanted him to lead me back to that cursed spot on the wall, to help me understand what had happened.

My brain wouldn't let me sleep that night. It perked up at every creak and murmur, waiting for my parents to arrive. I crept out of bed and shuffled down the quiet halls of the hostel. The moon shone through the windows, and I slipped out the front door.

The breeze whispered over the silvery landscape, the mountains a hulking shadow in the distance. I sat on the porch steps and hugged my knees. The night felt wild, eerie and magical at the same time, like anything could happen, good or bad. The hair rose on my arms, and I shivered.

I joined my teammates at breakfast, but my churning stomach wouldn't allow any more than a few sips of tea. I couldn't even look at the bowls of ceviche, the fish soup that appeared at almost every meal. My head throbbed.

Zach picked up his bowl and drank the liquid with a loud slurp and smack, trying to be funny. Becky giggled. My other teammates gave me smiles, pats on the back; they thought I was nervous about my final climb. Tungurahua was silent again, leaving little more than a layer of ash on the neighboring hillsides.

I caught Mr. S. watching me. His eyebrows were drawn, his forehead creased, but he didn't approach me to say anything. He looked like he'd come to the same realization, that something might have gone wrong for my parents way up high on the mountain. I looked away.

Summit attempts need to take place near dawn. Mountaineers trek to a camp high on the mountain, then sleep until just before midnight. Rising in the deep darkness of night, they begin their final ascent. They need to reach the summit and descend before the mountain wakes up.

Chimborazo wakes up around nine a.m. The sun warms the snow to a sugar-like consistency, ice melts, and rocks tumble. Several years ago, an avalanche killed ten climbers on the upper slopes of the mountain.

My parents and Uncle Max were expert mountaineers; they respected the mountain's power. They had turned away from summit attempts in the past. But an expedition can go terribly wrong even when the climbers do everything right. Conditions on mountains are out of their control, and nature runs its course no matter what.

My tagua bracelet was back on my wrist again, along with the one I had bought for Mom. The bracelets tangled and entwined, the beads rubbing together. All I could do was wait.

And worry. In my room, I unzipped my backpack pocket and reached for my worry stone. I fished around, pulling out a Starburst, a quarter, lint. No golden nugget. I dug through the rest of the stuff in my pack, pulling everything out one by one. Fleece jacket, water bottle, phone, wallet. My trusty, beat-up copy of Thoreau's

Walden

.

I felt all around the inside of my pack. More lint and a penny. Buena suerte.

I dropped to my knees and looked under the bed and all around the floor. The chunk of pyrite was too big to have slipped through the cracks in the planks.

I sat on the edge of my bed and dropped my head into my hands. Think, Cara, when did you last have it? I had turned the stone around in my hands before my climb yesterday, just like I always did. But everything after that was a muddle.

I shook out my fleece jacket and fanned out the books, knowing it was useless. A postcard slipped out from the pages of

Walden

. “Greetings from Ecuador” was scrawled across a photo of a llama standing in front of a mountain range. It made it look like the llama was speaking.

Dad

.

I smiled and flipped it over, squinting to read his messy handwriting.

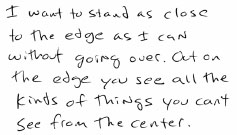

Dad always sent me postcards from his expeditions with lines of poetry or quotes from books. I had an entire bulletin board full in my bedroom at home. As usual, I didn't know exactly what this quote meant or where it came from, but it made me feel better. I reread the lines out loud, tucked the postcard back into my book, and returned everything to my backpack. Mom and Dad and Uncle Max were climbing to their edges. Now it was time for me to climb to mine.

I waited by myself in the isolation area, the last of my teammates to climb. I didn't have my worry stone, I didn't have my thermos of peppermint tea. I closed my eyes and imagined the golden stone in my hands, the warm peppermint tea, relaxing my throat, calming my insides.

A woman entered the tent and gestured, and I followed her outside. I stood at the base of the competition wall and scanned the final route. I pantomimed the first few moves to focus my mind. There was a looming overhang to conquer on this route as well, and it was even higher up on the wall, at least fifty feet. I would need to conserve my energy.

“Buena suerte,” I whispered.

I breathed deeply and climbed on. Slow and steady, just like my parents on their trek, step after step, one foot after the other, one hand after the other, until it became a meditation. I reached the overhang and focused my energy at my heart.

A loud grunt erupted from deep in my chest, and I launched over the ledge. My meditative pace continued and before I knew it, I was clipping the final bolt. I felt like I could keep going, just climbing and climbing. I peered over the top of the wall to the mountains in the distance and released a long sigh, sending my energy to Mount Chimborazo.

I was back on the ground before I noticed that my bracelets were gone. I touched my bare wrist. They must have scraped against a hold and snapped. I crouched at the base of the climb and searched, digging through the thick layer of shredded black rubber. Chalk dust scratched my throat, making me cough, but I couldn't find a single tagua bead. They had fallen through the cracks and empty spaces between the chips of rubber, buried below.

I sat on the grass and watched the last competitor in my age bracket, my back resting against the bleachers, legs splayed out in front of me. My knees and shins were dotted with fading bruises and new greenish purple ones from my slamming fall the day before. Was it simply dehydration? An attack of nerves? It didn't feel that way. It was like the universe had spoken to me. Was I being given a message? What was I missing?

Shouts and cheers jerked me back to attention. Coach Mel grabbed my hand and pulled me to standing.

“Third place. So close, Cara, so close.”

My brain slowly registered what had happened. Third place was not what I came here to accomplish, but it didn't stop my teammates from dancing around me. Someone picked me up, the curse of being small. Zach swung me around in a hug; he'd placed third in his division, too.

Blood rushed to my cheeks, and I couldn't help but smile, my heart opening to the joy around me. The first-place French climber hugged me and planted a quick kiss, kiss on my cheeks. I laughed, kissing the air beside her face. I scanned the crowd for my parents.

Zach hammed it up with his bronze medal and pulled me into pics right and left. It wasn't long before the media realized my parents were absent. The rumors flew.

My smile became tighter and tighter. My throat closed as tears swelled. I escaped to the outer edges of the crowd and breathed deeply to calm my trembling insides. Some part of me had truly expected my parents to show up, as if I was capable of making them appear through the strength of my will.

I overheard a reporter from

Rock and Ice

magazine speaking into a microphone in front of a camera.

“We've been told the American climbers Mark and Lori Jenkins and Max O'Connor were planning to summit Mount Chimborazo by a rarely attempted and extremely dangerous route up the east face of the mountain. And now ⦠they are missing.”

The woman spied me and strutted my way. I was so stunned by her speed, I stood frozen.

“We're here with Cara Jenkins, daughter of the missing climbers Mark and Lori Jenkins. Cara, you must be very worried. What have you heard about your parents?”

I stepped backward, but the woman thrust the microphone closer to my face.

“I haven't heard anything yet,” I stammered. I took another step backward, bumping into Becky, who had come up behind me.

Becky gave me a half hug and kept her arm draped over my shoulder. She flashed a sympathetic look at me, then at the camera. “It's just terrible,” she said.

“We've heard reports of several avalanches on the mountain,” the reporter continued. “Some are fearing the worst.”

My eyes swept the competition area. Where were my teammates when I needed to be picked up and carried away? Becky's mother approached, smoothing her hair and smiling at the camera. Her diamond earrings flashed in the sunlight. I recognized my chance and sidestepped out of Becky's grasp. If those two wanted the spotlight, they could have it.