The Articulate Mammal (3 page)

Read The Articulate Mammal Online

Authors: Jean Aitchison

(Cutler

et al.

2005: 1)

(A complete list of references quoted in the text is contained in the References on pp. 246–69.)

Both psychologists and linguists can be classified as social scientists, so in one way their approach has long been similar. All social scientists work by forming and testing hypotheses. For example, a psycholinguist might hypothesize that the speech of someone who is suffering from a progressive disease of the nervous system will disintegrate in a certain order, perhaps suggesting that the constructions the patient learned most recently will be the first to disappear. This hypothesis will then be tested against data collected from the speech of someone who is brain-damaged. This is where psychologists and

linguists sometimes differ. Psychologists test their hypotheses mainly by means of carefully controlled experiments. Linguists, on the other hand, test their hypotheses mainly by checking them against spontaneous utterances. They feel that the rigidity of experimental situations sometimes falsifies the results. Neither way is right or wrong. Provided that each side is sympathetic to and interested in the work of the other, it can be a great advantage to have two approaches to the subject. And when the results of linguists and psychologists coincide, this is a sure sign of progress.

Most introductory books published so far have been written by psychologists. A few have even argued that the name ‘psycholinguistics’ should be restricted to psychological experiments on language. This book is an attempt to provide an introduction to the subject from the linguist’s point of view – although inevitably and rightly, it includes accounts of work done by psychologists. It also covers some of the work done by both linguists and psychologists under the broad umbrella label ‘language and mind’, or (more recently) ‘cognitive linguistics’. This book does not presuppose any knowledge of linguistics – though for those who become interested in the subject, a number of elementary books are suggested on pp. 240–5.

Psycholinguistics is in many ways like the proverbial hydra – a monster with an endless number of heads: there seems no limit to the aspects of the subject which could be explored. This is a rather unsatisfactory state of affairs. As one researcher expressed it: ‘When faced with the inevitable question, “What do psycholinguists do?” it is somehow quite unsatisfactory to have to reply, “Everything”’ (Maclay 1973: 574). Or, as another psychologist put it:

Trying to write a coherent view of psycholinguistics is a bit like trying to assemble a face out of a police identikit. You can’t use all of the pieces, and no matter which ones you choose it doesn’t look quite right.

(Tanenhaus 1988: 1)

In this situation, it is necessary to specialize fairly rigidly. And amidst the vast array of possible topics,

three

seem to be of particular interest:

1

The acquisition problem

Do humans acquire language because they are born equipped with some special linguistic ability? Or are they able to learn language because they are highly intelligent animals who are skilled at solving problems of various types? Or could it be a mixture of these two possibilities?

2

The link between language knowledge and language usage

Linguists often claim to be describing a person’s representation of language (language

knowledge

), rather than how that knowledge is actually

used.

How then does usage

link up with knowledge? If we put this another way, we can say that anybody who has learned a language can do three things:

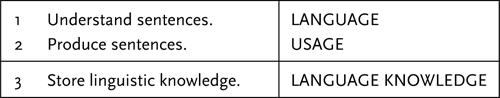

Many pure linguists claim to be interested in (3) rather than (1) or (2). What psycholinguists need to know is this: do the types of grammar proposed by linguists really reflect a person’s internalized knowledge of their language? And how do people make use of that knowledge in everyday speech?

3

Producing and comprehending speech

What actually happens when a person produces or comprehends a chunk of speech?

These are the three questions which this book examines. It does so by considering four types of evidence:

1 animal communication;

2 child language;

3 the language of normal adults;

4 the speech of aphasics (people with speech disturbances).

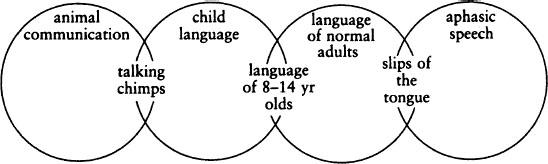

As the diagram below shows, these are not watertight compartments. Each type of evidence is connected to the next by an intermediate link. Animal communication is linked to child language by the ‘talking chimps’ – apes who have been taught a language-like system. The link between child and adult language is seen in the speech of 8- to-14-year-olds. The language of normal adults is linked to those with speech disturbances by ‘speech errors’, which occur in the speech of all normal people, yet show certain similarities with the speech of aphasics.

Before moving on to the first topic, the acquisition problem and the question of linguistic knowledge, we must make a few comments about the use of the word

grammar

.

We assume that, in order to speak, every person who knows a language has the grammar of that language internalized in their head. The linguist who writes a grammar is making a hypothesis about this internalized system, and is in effect saying, ‘My guess as to the knowledge stored in the head of someone who knows a language is as follows ‘For this reason, the word

grammar

is used interchangeably to mean both the internal representation of language within a person’s head, and a linguist’s ‘model’ or guess of that representation.

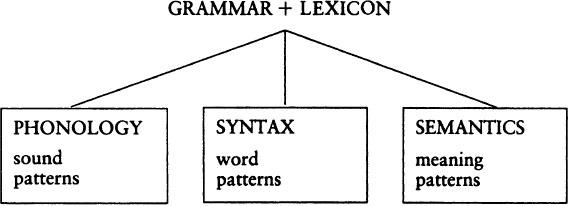

Furthermore, when we talk about a person’s internalized grammar the word

grammar

is being used in a much wider sense than that found in some old textbooks. It refers to a person’s total knowledge of their language. That is, it includes not just a knowledge of

syntax

(word patterns) but also

phonology

(sound patterns),

semantics

(meaning patterns), as well as the

lexicon

(the mental dictionary) which ties everything together.

Increasingly, linguists are finding that syntax and semantics are intrinsically linked together, and cannot easily be separated. It is far easier to split off phonology. Syntax and semantics together form the essence of any language. They, alongside the lexicon, will therefore be the basic concern of this book. Phonology will mostly be omitted, and only referred to where it illuminates syntactic and semantic problems.

Perhaps here we need to mention also a vast and woolly subject which is

not

the concern of this book – the relationship of language to thought. Although it is clear that thought is

possible

without language, it seems that people

normally

think in terms of their language. That is, a person’s thoughts are ‘pre-packaged’ into words and grammatical categories. This means that when we are discussing production and comprehension, we shall not spend time discussing an abstract layer of ‘concepts’ which some people have assumed to exist at a level ‘above’ language. When discussing, say, producing speech, we shall take it for granted that the first thing a person tells herself to do is, ‘Select the relevant words and syntax’ rather than ‘Package together concepts and see if they can be translated into language’. In other words, if it is necessary to take sides in the controversy as to which came first, language or thought, we are more on the side of the nineteenth-century poet Shelley, who said ‘He gave men speech, and speech created thought’ than that of the eighteenth-century lexicographer Samuel Johnson, who claimed that ‘Language is the dress of thought.’ Consequently, the vast and fascinating area known as ‘cognitive linguistics’, which links language with thought, will only intermittently be mentioned – though reading suggestions will be added in the Suggestions for Further Reading on pp. 240–5.

Another voluminous topic which is not discussed in this book is that of ‘communicative competence’. In recent years, a number of psychologists have made the rather obvious point that children do not merely acquire the structural patterns of their language, they also learn to use them appropriately within various social settings. Therefore, it is argued, psycholinguists should pay as much attention to social context as to language structure itself, particularly as children in the early stages of speech are heavily dependent on their surroundings. This work is interesting and important, and most people nowadays agree wholeheartedly that it is useless to consider child utterances in a vacuum. However, humans, if they so wish, are able to rely on structure alone when they communicate. They often manage to comprehend and produce quite unexpected and inappropriate utterances. In fact, it might even be claimed that the ultimate goal of language acquisition is to lie effectively, since ‘real lying … is the deliberate use of language as a tool … with the content of the message unsupported by context to mislead the listener’ (De Villiers and De Villiers 1978: 165). This book, therefore, takes more interest in the steps by which this mastery of structure is attained, than in the ways in which utterances fit into the surrounding context.

Finally, I have tried not to repeat material from other books I have written, though occasional references and outline notes are inevitable, particularly from

Words in the Mind: An Introduction to the Mental Lexicon

and

The Seeds of Speech: Language Origin and Evolution

.

1

____________________________

THE GREAT AUTOMATIC GRAMMATIZATOR

Need anything be innate?

He reached up and pulled a switch on the panel. Immediately the room was filled with a loud humming noise, and a crackling of electric sparks … sheets of quarto paper began sliding out from a slot to the right of the control panel … They grabbed the sheets and began to read. The first one they picked up started as follows: ‘Aifkjmbsaoegweztpplnvo qudskigt, fuhpekanvbertyuiolkjhgfdsazxcvbnm, peruitrehdjkgmvnb, wmsuy.…’ They looked at the others. The style was roughly similar in all of them. Mr Bohlen began to shout. The younger man tried to calm him down.