The Articulate Mammal (41 page)

Read The Articulate Mammal Online

Authors: Jean Aitchison

The notion of strategies therefore solves some problems, but raises others. Strategies cannot be totally replaced, but they need to be held in check and supplemented by more precise procedures. Let us go on to consider how researchers have tried to instill more orderliness into models of comprehension.

WORD-BY-WORD

As a reaction against the chaos of strategies, a number of researchers turned towards the neatness and orderly behaviour of computers. Perhaps they could program a computer so that it would be an ‘automatic parser’, that is, a machine which could unaided identify the syntactic role of each word, and show how they all fit together. Such machines move from one end of the sentence to the other, dealing with each group of words in turn, checking them against an internal grammar which contains information about the structure of English sentences. This is sometimes called a ‘left-to-right’ model, or in more fashionable terminology, an ‘incremental parser’, since the parser moves onwards by adding extra information word by word, in so far as this is possible.

Of course, when faced with a simple sentence such as:

PETRONELLA SAW A GHOST.

there is hardly any difference between a model which says ‘Assume you are dealing with an NP–V–NP structure’ (strategy model), and one which says ‘Work your way through the sentence word-by-word looking first for a noun phrase, then for a verb, then another noun phrase’ (left-to-right model). But the difference becomes apparent when we look at how to deal with questions.

Suppose we have a sentence which begins with the words:

WHICH ELEPHANT …?

This sentence could end in a number of different ways. We could say:

WHICH ELEPHANT CAN DANCE THE POLKA?

WHICH ELEPHANT SHALL I BUY?

WHICH ELEPHANT SHALL I GIVE BUNS TO?

In the first sentence, the elephant is the subject of the verb, the one who is dancing the polka; in the second, the elephant is the object, the thing being bought; in the third, it is the indirect object, the animal to whom something is being given.

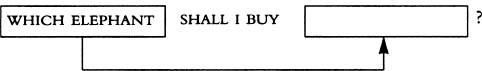

A dedicated strategy model would suggest that hearers start guessing immediately about the role of the word elephant, based on their expectations of the role elephants usually play in sentences. A left-to-right model, on the other hand, suggests that if hearers encounter a group of words which does not immediately fit into the straightforward NP–V–NP pattern, they do not make any rash guesses, they wait and see. They mentally store the words WHICH ELEPHANT in their memory until they have heard enough of the rest of the sentence to enable them to interpret it reliably. For example, in the case of WHICH ELEPHANT SHALL I BUY? they would wait until after the word BUY, since they know that the verb BUY usually has an object, the thing which is bought. They then mentally insert the stored phrase WHICH ELEPHANT into the gap where the object is usually found:

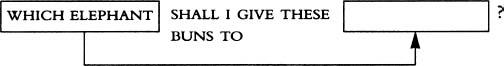

Similarly, in the sentence WHICH ELEPHANT SHALL I GIVE THESE BUNS TO? the hearers would store the words WHICH ELEPHANT until after the word TO. They would know that the word TO must normally be accompanied by a noun, so they would insert the stored phrase into the gap after TO:

But this type of decision making may be unnecessary. Early work on comprehension suggested that psycholinguists needed to make decisions about whether strategies or gap-filling models were preferable. Later work

has led to the realization that the human language processor is likely to be more powerful, and more commonsensical than was once assumed (e.g. Townsend and Bever 2001). And far more may be happening simultaneously than we previously realized. As a hearer works through a sentence, he or she may encounter temporary ambiguity quite often, but is often able to make a provisional decision, while still keeping other possibilities in mind. One interpretation is ‘foregrounded’, though others are kept in the background, ready to be moved forward if necessary. Hearers probably avoid making a definitive decision, if they are at all uncertain: having to go back and make a totally new analysis would be time-consuming and inefficient.

A solution which involves two layers of processing has also been proposed (Frazier and Clifton 1996). Primary parsing principles could first cut up any sentence into broad chunks. The ‘canonical sentoid’ strategy is possibly one of these, so are the more recently proposed principles which overlap with it, the Principles of Minimal Attachment and Late Closure (p. 200–1). These primary decisions may be followed by a second set of decisions, which look at smaller chunks and take individual lexical items into account.

Let us now assess the comprehension process. Left-to-right models may be right in assuming that speakers work through sentences in a principled way. But such models also present problems. A critical weakness is that they cannot cope with ill-formed, but comprehensible sentences, such as:

I HAVE MUCH PROBLEM IN MAKING TO WORK YOUR TELEPHONE.

They therefore need to be integrated with strategy models which can make guesses about imperfect utterances. A further possibility is that humans make a provisional decision, but keep likely alternatives in their mind, so that they can switch over to these if necessary. This compromise solution may be the correct one. The human mind is capable of much more simultaneous computation than was once assumed.

FURTHER DIFFICULTIES

So far, the factors we have discussed which affect comprehension have been mainly linguistic ones. But understanding speech may use abilities which relate to other aspects of human behaviour. In the next few pages we will discuss some aspects of sentence processing which involve other specific linguistic abilities, though we must bear in mind that it is not always easy to separate linguistic factors out from general cognitive ones, and researchers frequently disagree about which is which. Broadly speaking, a hearer is likely to find a sentence hard to comprehend if it goes beyond certain ‘psychological’ limits.

Let us begin by considering the amount of material which can be processed at any one time. Clearly, there is a limit on this. We know from numerous other areas of human behaviour that there is only a certain amount that human beings can cope with simultaneously, whether they are trying to remember things or are solving a problem. So a sentence that is long or involved will be difficult. Take length. It is often hard on a journey to follow the route directions of a passerby. People tend to say things like: ‘Take the third turning on the left past the fourth pub just before the supermarket next door to the church.’ Apart from anything else, this sentence is just too long to be retained in the memory. Before the speaker gets to the end, the hearer is likely to have forgotten the first part.

However, length alone is not particularly important. What matters is the interaction of length with structure. Early research suggested that listeners prefer to deal with the speech they hear sentoid by sentoid. As soon as one sentoid has been decoded, hearers possibly forget the syntax, and remove the gist of what has been said to another memory space (Fodor

et al.

1974: 339). The hearer ‘wipes the slate clean’, and starts afresh.

Subsequent research suggested that this view is somewhat over-simplified (e.g Flores d’Arcais 1988). Sentoids are cleared away only if their contents appear to be no longer needed. Speakers are able to retain sentoids in their memory to a greater or lesser extent, if they sense that this will help future processing.

But the overall conclusion is clear. Humans have limited immediate memory space and processing ability. Therefore they clear away sections of speech as soon as they have dealt with them, preferably sentoid by sentoid. This would explain not only why unusually long sentoids are difficult (as in the direction-finding example given earlier), but also, perhaps, why sentences which cannot easily be divided into sentoids are a problem. For example:

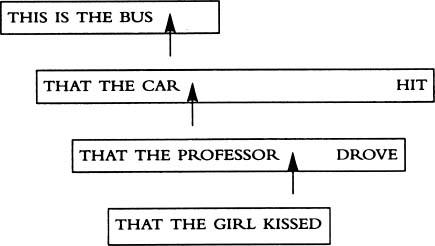

THIS IS THE BUS THAT THE CAR THAT THE PROFESSOR THAT THE GIRL KISSED DROVE HIT.

is more difficult than:

THIS IS THE GIRL THAT KISSED THE PROFESSOR THAT DROVE THE CAR THAT HIT THE BUS.

even though the second sentence has exactly the same number of words and almost the same meaning. Part of the trouble with the first is that you have to carry almost all of it unanalysed in your head. You have to wait until the end of the verb HIT that goes with CAR before you can divide it into sentoids:

However, in dealing with sentences which cannot easily be divided into sentoids like the one above, it is not only the memory load, but also the difficulty of processing three sentoids simultaneously which cause problems. Three are not impossible (as some people have suggested, e.g. Kimball 1973) because we can, after some thought, compose sentences such as:

THE NEWBORN CROCODILE [WHICH THE KEEPER [YOU WERE TALKING TO THIS AFTERNOON] LOOKS AFTER] IS BEING MOVED TO ANOTHER ZOO.

But in general it is unusual to find more than two sentoids being coped with easily, and two are more difficult than one. It is a fact about human nature that a person can deal only with a limited number of things at one time.

This leads us on to another difficulty, which overlaps with the simultaneous processing problem – that of interruptions. An interrupted structure is only slightly more difficult to process than an uninterrupted one, providing there are clear indications that you are dealing with an interruption. For example, the following sentence has a seventeen-word interruption:

THE GIRL [WHOM CUTHBERT KISSED SO ENTHUSIASTICALLY AT THE PARTY LAST NIGHT WHEN HE THOUGHT NO ONE WAS LOOKING] IS MY SISTER.

It is not particularly difficult to understand because the hearer knows (from the opening sequence THE GIRL WHOM …) that he is still waiting for the main verb. However, if there are no indications that an interruption is in progress, the sentence immediately increases in difficulty and oddness:

CUTHBERT PHONED THE GIRL [WHOM HE KISSED SO ENTHUSIASTICALLY AT THE PARTY LAST NIGHT WHEN HE THOUGHT NO ONE WAS LOOKING] UP.

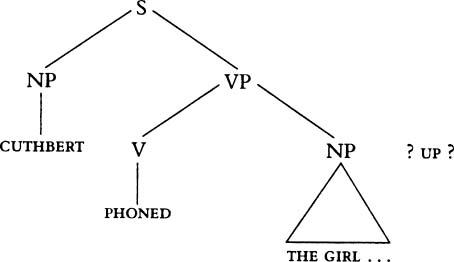

Here UP goes with PHONED, but the hearer has already ‘closed off’ that branch on his mental tree. He has not left it ‘open’ and ready for additional material: